Overview: figures at a glance

How we calculate these figures

The 2017 round-up figures compiled by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) include professional journalists, media workers and citizen-journalists, who are playing an increasing role in the production of news and information, especially in countries with oppressive regimes and countries at war, where it is hard for professional journalists to operate. As far as possible, the round-up nonetheless distinguishes professional journalists from the other kinds in its breakdowns, in order to facilitate comparison with other years.

Compiled by RSF every year since 1995, the annual round-up of abuses and acts of violence against journalists is based on precise data. We gather detailed information that allows us to affirm with certainty or a great deal of confidence that the detention, abduction, disappearance or death of each journalist was a direct result of their journalistic work. With regard to deaths, we distinguish as much as possible between journalists who were deliberately targeted and those who were killed while reporting in the field. We do not include journalists in the round-up when we have been unable to affirm with a great deal of confidence that they were killed in connection with their work, or when the case is still being investigated.

JOURNALISTS KILLED

1-The figures

65

Journalists killed in connection with the provision of news and information

-18% compared with the figures of 2016

Comprising

50 professional journalists

7 citizen-journalists

8 media workers

1035 PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS KILLED IN THE PAST 15 YEARS

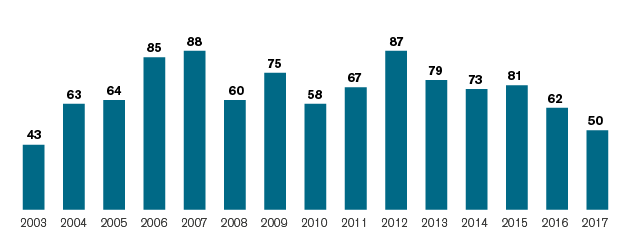

2017: LEAST DEADLY YEAR FOR JOURNALISTS IN 14 YEARS

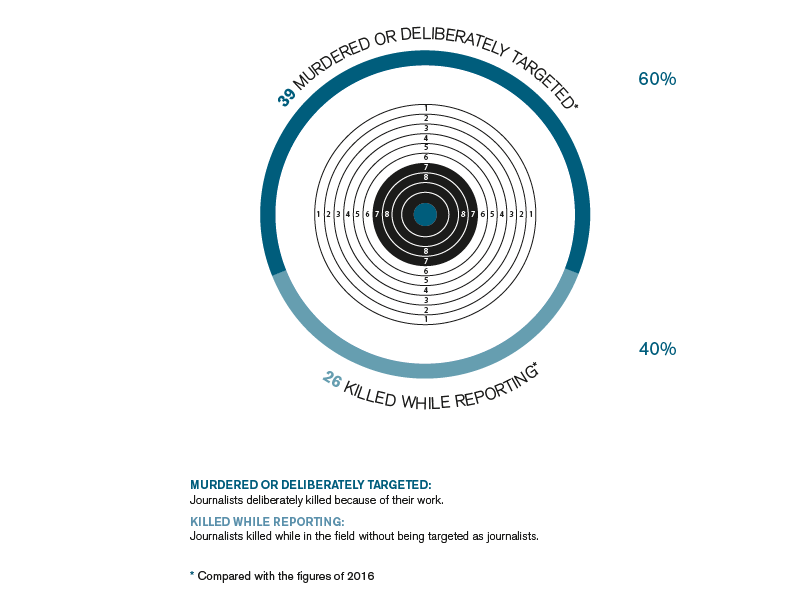

A total of 65 journalists (including professional journalists, citizen-journalists and media workers) were killed worldwide in 2017. Twenty-six of them were killed in the course of their work, the collateral victims of a deadly situation such as an air strike, an artillery bombardment, or a suicide bombing. The other 39 were murdered, and deliberately targeted because their reporting threatened political, economic, or criminal interests. As in 2016, most of the deaths were targeted (60%). The aim in each case was to silence them.

The 2017 death toll is a slight fall (-18%) from the 2016 figure (79). In the professional journalist category (50 this year), RSF notes that 2017 has been the least deadly year for professional journalists in 14 years (see graphic).

WHY THIS TREND?

This downward trend may be due in part to the many campaigns waged by international NGOs and media organizations on the need to provide journalists with more protection. More security training has helped to better prepare journalists for visits to hostile terrain. Thought has also been given to the status of freelancers, and initiatives have been undertaken with the goal of giving them the same kind of protection as staffers. These measures include the creation in 2015 of the A Culture of Safety (ACOS) Alliance, a coalition of major news companies, journalism organizations and freelancers, with the aim of developing and adopting worldwide protection standards for freelancers.

Intensive lobbying of governments and international bodies by NGOs such as RSF that defend and protect journalists has also been productive. With the United Nations General Assembly and Security Council, the UN Human Rights Council and the Council of Europe, RSF has promoted recommendations on the safety of journalists that have been reflected in various resolutions. The latest of these was adopted by the UN General Assembly on November 20. Its central focus was on the specific risks faced by women journalists in the exercise of their work and the need to address sexist discrimination, violence, and harassment, including online harassment.

The downward trend is also due to journalists abandoning countries that have become too dangerous. Countries such as Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya have been haemorrhaging journalists. Or journalists have chosen to switch to a less dangerous profession. But inability to report without risking one’s life is not limited to countries at war. Many journalists have either fled abroad or abandoned journalism in Mexico, where the criminal cartels and local politicians have imposed a reign of terror.

2-The world’s deadliest countries

SYRIA AND MEXICO, THE DEADLIEST COUNTRIES FOR REPORTERS

As has been the case for the past six years, Syria continued to be the world’s deadliest country for journalists with 12 killed, but Mexico was close behind with 11 killed. All of them were deliberately targeted. Of countries not at war, Mexico was the deadliest for reporters in 2017, as it was last year.

In the land of drug cartels, journalists who cover political corruption or organized crime are almost systematically targeted, threatened, and often gunned down in cold blood. The murder of Javier Valdez Cárdenas in Culiacán (in Sinaloa state) on May 15 sparked a public outcry. Aged 50, this veteran reporter for AFP and two local papers, La Jornada and Riodoce, specialized in writing about drug trafficking. His latest book, Narco-journalism, recounts the tribulations of Mexican journalists who, despite the dangers, try to cover the activities of the country’s extremely violent narcos (drug traffickers). Ten other Mexican journalists paid with their lives in 2017 for covering sensitive stories. Most of these murders remain unpunished, an impunity attributable to Mexico’s widespread corruption, especially at the local level where officials are often directly linked to the cartels.

Torn by a never-ending bloody war, Syria has been the world’s deadliest country for journalists since 2012. There is danger everywhere on the ground and journalists, professional or not, are permanently exposed to sniper fire, missiles, improvised explosive devices or suicide bombers. Syrian journalists are the most exposed, especially as the presence of foreign reporters has fallen sharply in recent years. Foreign reporters have nonetheless begun to return, especially to the north, to the Rojava region to cover the battles waged by Arab and Kurdish forces against Islamic State in Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor.

AFGHANISTAN AND IRAQ: PREDATOR COUNTRIES

The same goes for Afghanistan, where nine national journalists were killed this year. The two professional journalists and seven media workers were killed in three different attacks, one against the local headquarters of the national radio and TV broadcaster in Jalalabad in May, and two in Kabul in May and November.

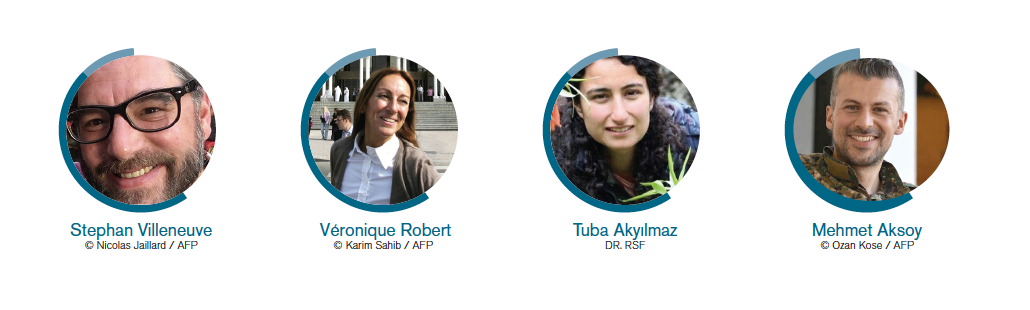

In Iraq, eight journalists were killed this year. Here too, it was local journalists who were targeted. The pro-government TV broadcaster Hona Salaheddin lost two journalists, who were killed by Islamic State fighters. The role of the lesser known but challenging profession of fixer was highlighted when Iraqi Kurdish journalist Bakhtiyar Haddad was killed in Mosul in June along with the two foreign reporters for whom he was fixing, French journalist Stephan Villeneuve and Swiss journalist Véronique Robert.

PHILIPPINES, ASIA’S DEADLIEST COUNTRY

Shortly after being elected president of the Philippines in May 2016, Rodrigo Duterte made this cryptic but alarming comment: “Just because you’re a journalist you are not exempted from assassination, if you’re a son of a bitch.” The threat proved to be more than just talk in 2017, with at least five journalists targeted by gunmen. Four of them succumbed to their injuries. The Philippines thus resumed a grim trend going back more than decade — one that was interrupted only in 2016, an exceptional year in which no journalist was killed.

3- Seven reporters killed in a foreign country

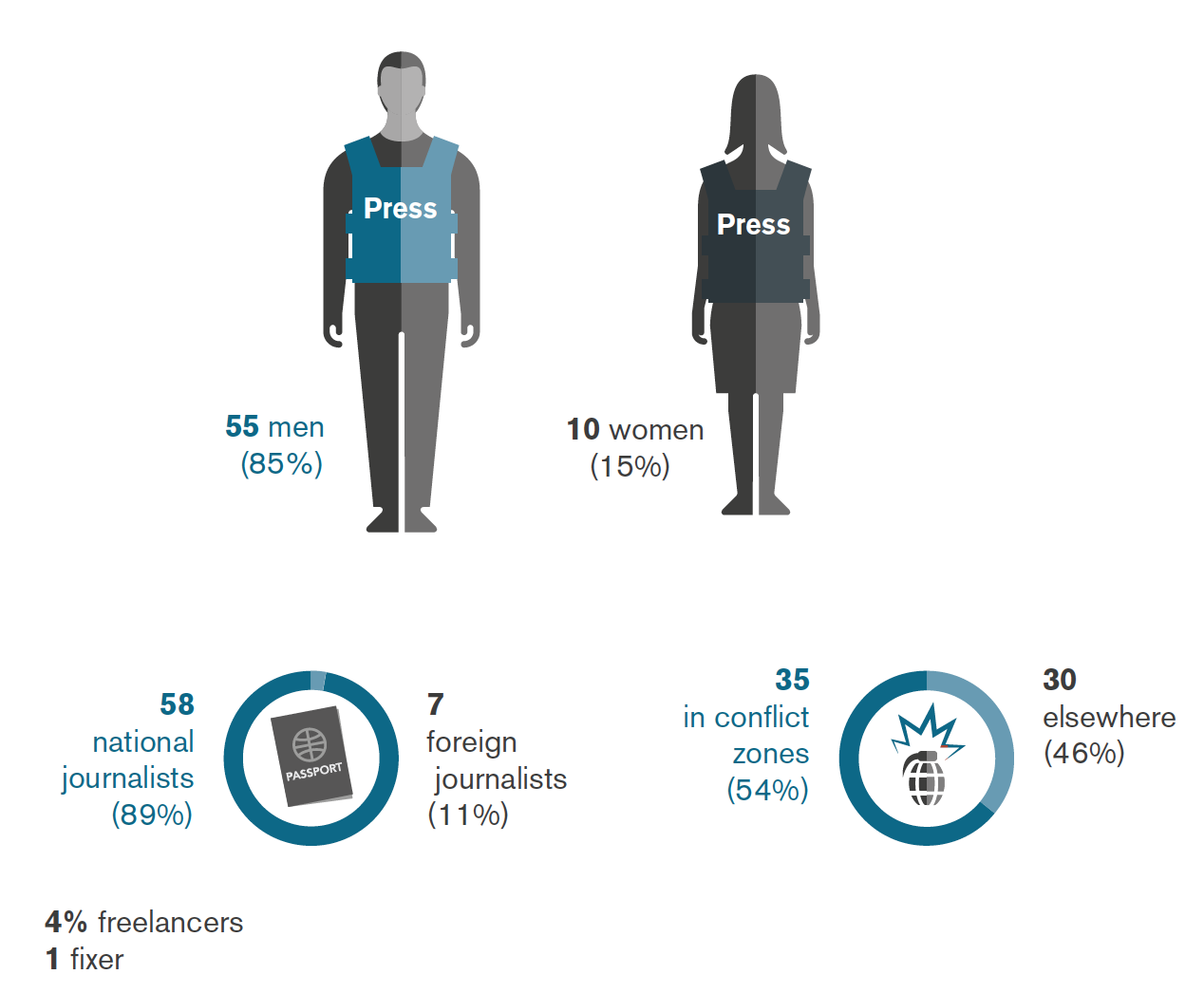

Of the 65 journalists killed in 2017, 58 (89%) were killed in their own country and seven were killed while reporting in another country.

Three foreign journalists were killed while covering the war in Iraq in 2017 . They included Stephan Villeneuve and Véronique Robert, two experienced war reporters who were preparing a report for the French TV current affairs program Envoyé Spécial. They were fatally injured by an improvised explosive device while accompanying an Iraqi special forces unit on June 19, 2017.

Tuba Akyılmaz, a Turkish journalist known professionally as Nuzhian Arhan, who reported for the feminist news website Sujin and the Kurdish news agency RojNews, was fatally hit in the head by sniper fire in March in the northern city of Sinjar, where she was covering conflict involving Kurdish forces.

British citizen-journalist Mehmet Aksoy was killed on the other side of the border in October. The editor of The Kurdish Question website, he went to Syria to do a report on fighting involving Syrian Kurdish forces and was killed in an Islamic State attack on a military checkpoint in Raqqa.

Conflicts that were less covered by the media proved just as deadly. American freelance reporter Christopher Allen was killed in South Sudan in August. He was killed by a shot to the head in the far south of the country during clashes between the South Sudanese army and members of the SPLA-IO rebel group with whom he was embedded. Although, when shot, he was wearing a vest that was clearly marked “Press” and despite the fact that he worked for Al-Jazeera, The Independent, Vice News and The Telegraph, the information minister said he felt no responsibility for Allen’s death because he died alongside his rebel comrades.

Honduran journalist Edwin Rivera Paz thought he was escaping danger when he fled to the Mexican state of Veracruz after his colleague, Igor Padilla, was murdered in Honduras. But gunmen shot Rivera dead in broad daylightin Veracruz on July 9, 2017. No information about the investigation into his murder has been provided by either the Mexican or Honduran authorities.

Kim Wall was a respected Swedish freelancer who had worked for leading media outlets such as The New York Times and The Guardian. She had travelled the world in the course of her reporting but it was in Denmark, no more than 50 km from her Swedish birthplace, that she met her death. Planning to do a profile of Danish inventor Peter Madsen, she set off with him on August 10 near Copenhagen in the small submarine he had built. Thereafter, all trace of Wall was lost until her dismembered remains were found at sea and on nearby beaches in the days and weeks that followed. Madsen is now detained and has been charged with her murder.

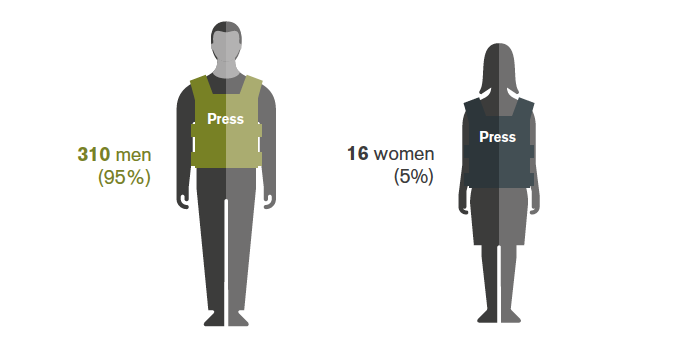

4-Twice as many women killed in 2017

Ten women journalists were killed this year, as compared to five last year. Many of the victims were experienced and determined investigative reporters with an abrasive writing style. Despite receiving threats, they continued to investigate and expose corruption and other cases involving politicians or criminal groups, and they paid for this with their lives.

The targeted car bomb that killed journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia in Bidnija, Malta, on October 16 sent a shockwave through her island nation and the rest of Europe. In her blog Running Commentary, which she had been writing since 2008 and which sometimes had as many as 400,000 page views a day, she denounced government corruption, bribery, illegal trafficking, and offshore banking in Malta, the European Union’s smallest country. She had also written many articles about the involvement of close associates of Prime Minister Joseph Muscat in operations exposed by the Panama Papers. Many European leaders have called for an independent international investigation into her murder.

According to RSF’s tally, Caruana Galizia’s murder was the fourth deadly attack on a journalist or journalists in the European Union in the past ten years. It was preceded by the massacre of seven Charlie Hebdo journalists in Paris on January 7, 2015; the murder of Greek journalist Socratis Guiolias, a radio station director and website writer, who was gunned down outside his home in 2010; and the murder of Croatian journalist Ivo Pukanic, a columnist for one of his country’s leading weeklies, Nacional, who was killed by a bomb left beside his car outside the newspaper in 2008.

Gauri Lankesh was killed by gunmen who shot her seven times as she was opening the door to her home in Bangalore, in southern India, on the evening of September 5. Aged 55 and the editor of the weekly Lankesh Patrike, she was known for the courage and determination with which she defended women’s rights and criticized the caste system and Hindu nationalism. She had received death threats, especially on the Internet, where supporters of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party had often attacked her. Her last editorial explained how fake news had contributed to the BJP’s election victory in 2014. Progress in the murder investigation is slow. Since her death, several Indian journalists critical of the government have received death threats that referred to her murder.

Miroslava Breach Velducea was fatally riddled with bullets while in her car on March 23 in Chihuahua, the capital of the northern state with the same name. Chihuahua is one of the most violent states in Mexico. A reporter for the Norte de Juárez and La Jornada newspapers, she covered organized crime and local government corruption. A few days before her death, she wrote a story about an armed conflict between the two leaders of a criminal group linked to the Juárez Cartel. Eight months after her murder, the investigation has stalled. The Chihuahua authorities announced in April that they had identified her killers, but have said nothing significant about the case since then. Breach’s family and colleagues have struggled to get access to details of the investigation.

DETAINED JOURNALISTS

The figures

326

Detained journalists

-6% compared to 2016

Comprising 202 professional journalists

107 citizen-journalists

17 media workers

Worldwide, a total of 326 journalists are detained in connection with the provision of news and information as of December 1, 2017. This is fewer than last year, when 348 journalists were detained (187 professional journalists, 146 citizen-journalists and 15 media workers). Ultimately, the number of citizen-journalists has fallen – especially in China, where the lack of information about the fate of journalists complicates the compiling of statistics.

While the overall trend is downward, some countries moved in the opposite direction, detaining an unusual number of journalists in 2017. This was the case in Morocco, where a professional journalist, Hamid El Mahdaoui, four citizen-journalists and three media workers are currently held in connection with their coverage of a wave of protests in the northern Rif region since 2016, a highly sensitive issue for the government. A year ago, not a single journalist was detained in Morocco. In Russia, pressure is growing both in Moscow and the provinces on independent media and investigative journalists who cover subjects such as corruption. Five journalists and one blogger are currently in prison.

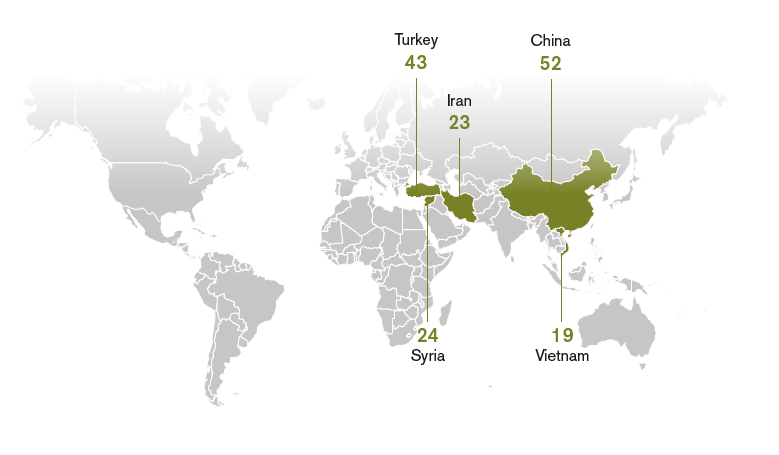

2 – The world’s five biggest prisons

NEARLY HALF OF THE WORLD’S IMPRISONED JOURNALISTS ARE BEING HELD IN JUST FIVE COUNTRIES

CHINA: SLOW DEATH BEHIND BARS

China continues to be the world’s biggest prison for journalists (all categories combined) and continues to improve its arsenal of measures for persecuting journalists and bloggers. The government no longer sentences its opponents to death but instead deliberately lets their health deteriorate in prison until they die.

Nobel Peace laureate Liu Xiaobo, who was also an RSF Press Freedom laureate, and the blogger Yang Tongyan were both diagnosed with terminal-stage cancer this year while serving long jail sentences and died shortly after being transferred to hospital. The international community now fears for the life of Huang Qi, the founder of the 64 Tianwang news website and winner of the RSF Press Freedom Prize in 2004, who is being subjected to beatings and denial of medical care in a Mianyang detention center in an attempt to force him to plead guilty.

TURKEY: PROVISIONAL DETENTION AS A PUNISHMENT

Prey to an unprecedented purge since a coup attempt in July 2016, Turkey continues to be the world’s biggest prison for professional journalists (42 + 1 media worker). Under the state of emergency, the right to due process no longer exists and arbitrary decision-making affects everyone. Criticizing the government, working for a “suspect” media outlet, contacting a sensitive source or even just using an encrypted messaging service all constitute grounds for jailing journalists on “terrorism” charges.

Most of the detainees have yet to be convicted. Provisional detention, which is supposed to be an exceptional measure, is becoming systematic and permanent in Turkey. Some journalists have been awaiting a verdict behind bars for 18 months. This is the case with Şahin Alpay of the newspaper Zaman, Nazlı Ilıcak, a journalist who worked for the newspaper Bugün, and DIHA reporter Nedim Türfent. Such arbitrary methods are now being employed with foreign journalists as well, albeit exceptionally. A young French reporter, Loup Bureau, was held for 51 days in the summer. French photographer Mathias Depardon was held for a month in the spring before being expelled.

The RSF round-up’s detention figures are based on a rigorous methodology that aims to establish on a case-by-case basis that the detained journalist was arrested in connection with their work as a journalist and not for another reason. Of the approximately 100 journalists detained in Turkey, RSF is currently able to state that at least 43 are being held because of their journalism. Many other cases are currently being investigated.

The RSF round-up’s detention figures are based on a rigorous methodology that aims to establish on a case-by-case basis that the detained journalist was arrested in connection with their work as a journalist and not for another reason. Of the approximately 100 journalists detained in Turkey, RSF is currently able to state that at least 43 are being held because of their journalism. Many other cases are currently being investigated.

VIETNAM JOINS THE LEADERS

Vietnam entered the ranks of the world’s five biggest prisons for journalists in 2017 with 19 now detained, overtaking Egypt, which currently has 15 journalists in its prisons, compared with 27 this time last year. Using censorship, arbitrary detention, and covert state violence, the Vietnamese regime has conducted an unprecedented crackdown on the freedom to inform in recent months in which at least 25 bloggers have been arrested orexpelled. The fact that 19 bloggers are currently detained explains why RSF is continuing its #StopTheCrackdownVN campaign.

3-Detained to set an example

Journalists are not arrested and prosecuted solely because of what they write. Many of them are left to fester in the prisons of authoritarian regimes in order to serve as an example that is meant to terrorize and silence their colleagues, or serve as leverage in conflicts that do not directly concern them.

This is the case for Mahmoud Hussein Gomaa, an Egyptian journalist who has been held for nearly a year without any solid charge brought against him. Employed in Doha by the Qatari TV broadcaster Al Jazeera, the Egyptian government’s bête noire, he made the mistake of returning to Egypt for end-of-year festivities in 2016. Clearly the victim of his country’s war with his employer, he is currently charged with inciting hatred and publishing false information.

Die Welt correspondent Deniz Yücel, who has been imprisoned in Turkey since February 2017, is also the victim of a conflict for which he is not responsible. A Turkish-German dual national, the 44-year-old Yücel is accused of “terrorist propaganda” and “inciting hatred,” but has yet to be issued a proper indictment. President Erdoğan has called him a spy and a criminal in speeches and seems to have made him a hostage to Turkey’s increasingly stormy relations with Germany.

Die Welt correspondent Deniz Yücel, who has been imprisoned in Turkey since February 2017, is also the victim of a conflict for which he is not responsible. A Turkish-German dual national, the 44-year-old Yücel is accused of “terrorist propaganda” and “inciting hatred,” but has yet to be issued a proper indictment. President Erdoğan has called him a spy and a criminal in speeches and seems to have made him a hostage to Turkey’s increasingly stormy relations with Germany.

Nguyen Ngoc Nhu Quynh, who wrote under the name of “Me Nam” (Mother Mushroom), is one of the many bloggers who have been arrested since the Vietnamese Communist Party’s hardliners gained the upper hand over the reformers in the 2016 congress and began tightening the party’s grip on news and information. For being one of Vietnam’s leading free speech exponents and, in particular, for daring to tackle the issue of police violence in her posts on social networks, Me Nam was given a ten-year jail sentence on a charge of anti-state propaganda at the end of a one-day secret trial in June.

Ahmed Abba, a Radio France Internationale correspondent in Cameroon, is another collateral victim of national issues. Every kind of pretext is used to punish Cameroonian reporters who mention crises such as the Boko Haram insurrection in the north of the county or anti-government protests in the English-speaking regions. The prolonged detention of Abba, a respected journalist, reflects the government’s determination to control the public discourse and avoid any questioning of its authority. Despite repeated calls for Abba’s release from RSF, journalists’ associations, and international organizations, he was sentenced in April 2017 to ten years in prison on a charge of “laundering the proceeds of a terrorist act.” A court is due to rule on his appeal on December 21.

JOURNALISTS HELD HOSTAGE

1-The figures

54

Journalists currently held hostage

+4% compared to 2016

Comprising

44 professional journalists

7 citizen-journalists

3 media workers

Hostages: RSF regards journalists as hostages when they are being held by non-state actors that threaten to kill or injure them, or continue to hold them as means of pressure on a third party (a government, organization, or group) with the aim of forcing the third party to take a particular action. Hostages may be taken for political reasons, economic reasons, (for ransom) or both.

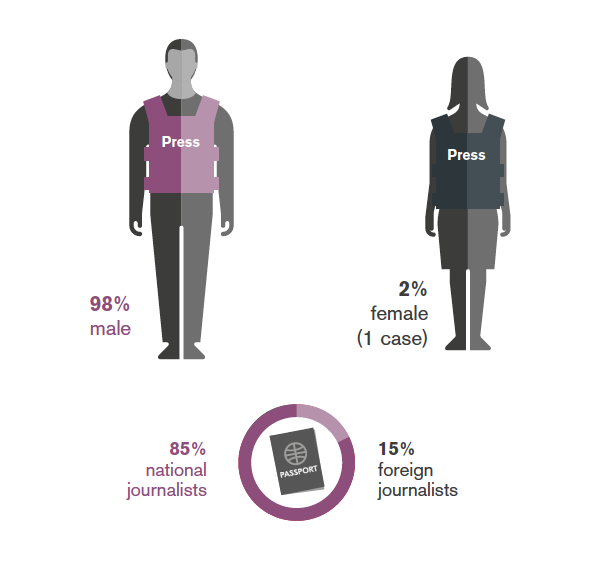

Worldwide, a total of 54 journalists are currently held hostage, compared with 52 on the same date a year ago (a 4% increase). While the number of foreign hostages has increased slightly (+14%), more than three quarters of the hostages are national journalists — often poorly paid freelancers working in extremely risky conditions. Citizen-journalists are now paying a heavy price. A total ofseven citizen-journalists are currently held by armed groups, compared with four this time last year. The increase confirms their growing involvement in the gathering of news and information, especially in war zones that have become inaccessible to professional journalists.

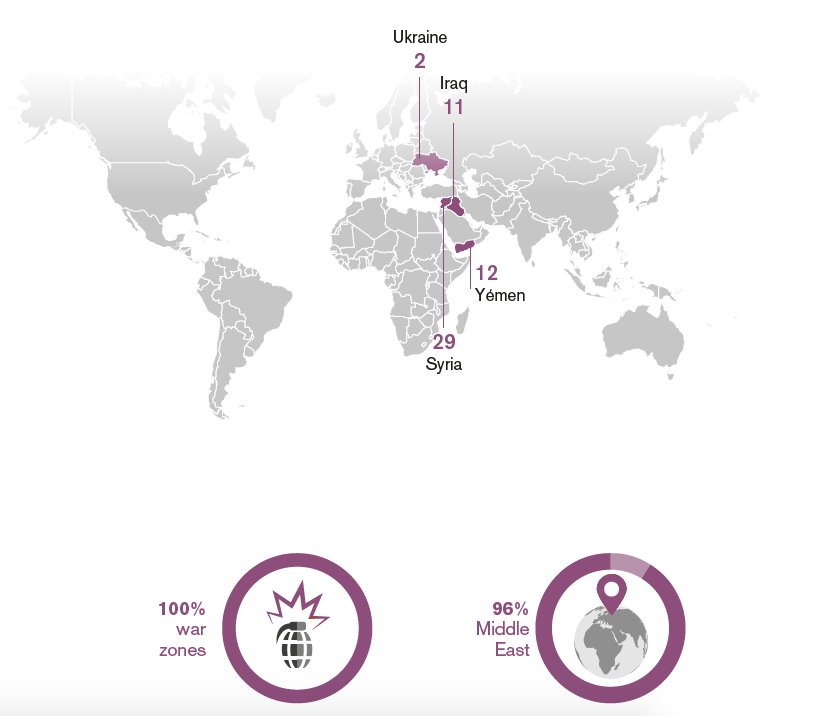

CONCENTRATED IN FOUR COUNTRIES

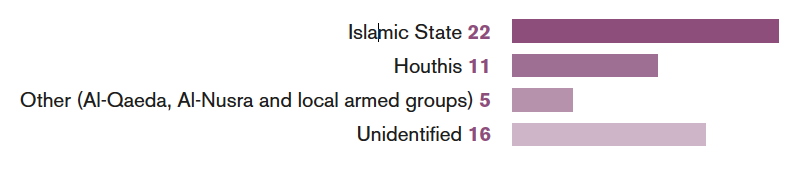

The Middle East’s fracture lines continue to be the world’s most dangerous regions for journalists. Yemen is sinking ever deeper into a war in which one of the factions, the Houthis, tolerate no criticism and are now holding 11 journalists and media workers, compared with 16 this time last year. Another journalist is being held hostage in Yemen by Al-Qaeda. Meanwhile, in Syria and Iraq, 40 journalists continue to be held by Islamic State and other radical Islamist groups such as Al-Nusra.

Outside the Middle East, the only country with hostages is Ukraine, where the separatist forces in the east tend to regard the few remaining critical journalists as spies. Two journalists are currently held in the self-proclaimed “republics” of the Donbass This is far fewer than at the peak near the start of the conflict in 2014, a year when more than 30 journalists were kidnapped. The decline in the intensity of the fighting, the fact that the front line is now stationary, and the almost complete absence of critical or foreign reporters in the separatist areas have all helped to reduce the practice of hostage-taking.

THE MAIN HOSTAGE-TAKERS

For armed groups, abduction is a business that is profitable and practical in many ways. It allows them to impose terror and obtain the complete submission of potential observers while using ransoms to fund their war. The increase seen this year in the number of hostages in Syria and Iraq is nonetheless due mainly to the fact that RSF has included cases that had not previously been tallied, either because they were still being verified or because the families did not want their cases made public.

While the overall number of hostages has not changed significantly, the military setbacks suffered by Islamic State in 2017 and the loss of its main strongholds on both sides of the border between Iraq and Syria have not yet been reflected in any improvement in the safety of journalists. A South African photo-journalist, Shiraaz Mohamed, was kidnapped at the start of the year (see below in Syria, No.1 for foreign hostages).

RSF has not been able to obtain any information about the journalists who were held hostage in the cities of Mosul and Raqqa, which were recently retaken by Iraqi forces and a US-backed Arab-Kurdish coalition. The creation of “de-escalation zones” in the spring of 2017 with the aim of ending violence in several Syrian regions has not been accompanied

by any visible improvement for hostages. The relatives of the activist and citizen-journalist Samar Saleh and her fiancé Mohamed al-Omar, who was freelancing for the Syrian opposition broadcaster Orient TV, are still without news of them. They were kidnapped on a street in Atareb, a town near Aleppo, on August 9, 2013 while filming its reconstruction. Atareb is now located in one of the de-escalation zones where the opposing forces are supposed to observe a cease-fire.

2-Media blackout

At least 22 Syrian journalists and 11 Iraqi journalists are currently held hostage in their respective countries. The exact number of national journalists in captivity is still hard to calculate, as the families and colleagues often prefer not to report their disappearance for fear of disrupting negotiations and delaying their release. It is often the kidnappers themselves who insist on silence. The media blackout may last for several years in some cases. More than three years went by before Kamaran Najm’s capture was revealed.

A respected Iraqi photo-journalist, Najm was injured and kidnapped by Islamic State on June 12, 2014 while covering fighting between Kurdish Peshmerga and IS in the Kirkuk region. Najm not only worked for such prestigious international media outlets as Der Spiegel, The Times, Vanity Fair, Washington Post and NPR but also founded the first Iraqi photo agency Metrography. The day after his abduction, his kidnappers allowed him to call a relative to confirm that he had been abducted and to warn that he could be endangered by any media attention to his abduction. His family and colleagues said nothing for three years. They finally lifted the media blackout because his abductors never contacted them again.

3-Syria, No.1 for foreign hostages

As far as RSF knows, seven foreign journalists are currently held hostage in Syria. Three of them have been held for more than five years. Austin Tice, an American journalist who worked for the Washington Post and Al Jazeera English, and Bashar al-Kadumi, a Jordanian journalist who worked for Al-Hurra TV, were abducted in August 2012. Tice was abducted in a Damascus suburb; al-Kadumi in Aleppo. According to RSF’s information, Tice is not being held by an Islamist group.

The British reporter John Cantlie was abducted a few months later, in November 2012, along with his American colleague James Foley, who was murdered by Islamic State on August 19, 2014. Cantile has not been treated as a typical hostage by his captors. Used by his abductors for media propaganda, he has been shown from time to time in staged videos praising Islamic State, each time appearing more haggard and emaciated. His last appearance, on the streets of Mosul, was in December 2016.

As with national journalists, the fate of kidnapped foreign journalists is largely unknown. Even the exact identity of their kidnappers is often hard to establish. A Sky News Arabia crew consisting of Mauritanian reporter Ishak Moctar and Lebanese cameraman Samir Kassab, disappeared while reporting in Aleppo in October 2013. The Lebanese newspaper Al Joumhouria reported six months later that they were alive and had been moved to Raqqa province but provided no further detail. There has been no news of them since then.

Japanese freelance journalist Jumpei Yasuda has been a hostage since the summer of 2015. Since then, the only proof that he is still alive has been a video recorded on his 42nd birthday in March 2016. It contained no indication of his kidnappers’ identity. Nothing is known about the current status of Shiraaz Mohamed, a South African freelance photo-journalist who was working for the Gift of the Givers Foundation when he was abducted along with two of the foundation’s employees near the Turkish border in January. They were kidnapped by individuals who identified themselves as “representatives of all the armed groups in Syria” and said they wanted to “settle a misunderstanding.” They released the two employees but not Mohamed. His family and the NGO continue to await evidence that he is still alive.

MISSING JOURNALISTS

Samar Abbas missing since January 7 in Pakistan

Of the five Pakistani bloggers who were abducted in January 2017, four were released after being held for several weeks but the fifth, Samar Abbas, never reappeared. Aged 38 and based in Karachi, Abbas founded the Civil Progressive Alliance Pakistan, a group that defends human rights and religious freedom and posts independently-reported information on its website with the aim of offsetting statements made by security forces and religious extremists. When Abbas went to the capital, Islamabad, on January 7, his family say they were in constant contact with him until his mobile phone suddenly went dead later that day. His disappearance was reported on January 14. His wife and three children have received no news of him since then. One of the four released bloggers, who has fled the country, has accused the Pakistani military intelligence services of responsibility. This accusation has been met with official denials. The other three bloggers refuse to provide any details about where they were held.

Utpal Das missing since October 10 in Bangladesh

The mother of Utpal Das spent October 31 beside her phone in the hope that he would call her on his 29th birthday but the phone did not ring and, like every other day since October 10, it brought no news of her son. No one has heard from Das, a senior reporter for the Dhaka-based news website Purboposhchimbd.news, since he left his office at around 4 p.m. on October 10. His editor reported him missing on October 22 and his father filed a separate missing report the next day. The police have found no trace of Das, who specialized in politics and was preparing a story about the ruling Awami League at the time of his disappearance. Around 100 journalists formed a human chain in Dhaka on November 8 to draw attention to his disappearance and to relay his family’s request for Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to intervene.

RSF regards journalists as missing when there is not enough evidence of their death or abduction and no credible claim of responsibility for their death or abduction has been made.

ACTION TAKEN BY RSF

Forbidden Stories, a weapon against censorship

It is the right to news and information of millions of citizens that has been sacrificed yet again in 2017 by means of these acts of violence and abuses against journalists. The world’s major problems, such as corruption, environmental scandals and violent extremism, cannot be addressed if journalists are not playing their essential role properly. Journalists must be able to work in a safe environment, and impunity for the perpetrators of abuses against journalists must be ended.

With these concerns in mind, RSF and Freedom Voices Network launched a joint project called Forbidden Stories in November to support investigative journalism and circumvent censorship. The project aims to provide a secure online location for the material and stories that journalists are working on so that, if they are arrested or killed, these stories are not lost.

Journalists who feel threatened can store sensitive work in an encrypted format with Forbidden Stories. If journalists are threatened and cannot continue their investigative reporting, the staff at Forbidden Stories will be able to access this sensitive material and share it with a network of international media that will work together to complete the research and publish the story as widely as possible. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) is a partner in this project.

By protecting and continuing the work of journalists who are unable to pursue their investigative reporting, Forbidden Stories wants to sent a powerful message to the enemies of the freedom to inform: “You can try to stop the messenger, but you won’t get to stop the message.”

Need to strengthen international protective mechanisms

This year, 2017, has seen a growing international recognition of the need for concrete mechanisms to protect journalists all over the world, thanks in particular to RSF’s work with the #ProtectJournalists coalition. In November, United Nations secretary-general Antonio Guterres announced the creation of a network of focal points within the UN’s main programs, agencies, and funds for sharing information about journalists in danger, and for coordinating and harmonizing strategies for protecting journalists worldwide. This announcement came a few months after Guterres appointed Ana-Maria Menéndez, his senior adviser on policy, as the focal point in his office, to receive information about urgent cases of journalists in danger and help arrange a rapid international response, as requested by RSF and the #ProtectJournalistscoalition.

This initiative is a significant first step inasmuch as the UN Plan of Action and the many UN resolutions on the safety of journalists had remained, until then, virtually dead letter. To go further, the coalition is pressing the UN and its member states to create the position of Special Representative to the UN Secretary-General for the Safety of Journalists. With a specific mandate, the ability to act quickly and with sufficient political weight to coordinate the focal points, the Special Representative would be able to confront governments not abiding by their obligations. Several governments have already declared their support for RSF’s proposal and groups of friends for the safety of journalists, consisting of UN and UNESCO member states, have been formed in New York, Geneva and Paris.

Source: RSF