Farmer Suleiman Al-Hussein inspects what remains of his car after it was targeted by an FPV suicide drone in Qastoun town, west of Hama, 6 August 2024 (Mousaab al-Yaseen).

Musab Al-Yassin – Bashar Al-Fares

This investigation was finished on 18 October 2024 and was scheduled to be published in December 2024, but publication was delayed due to the liberation of Syria and the fall of the Assad regime.

No one will farm the land and rejoice in its harvest anymore. It all vanished in a second, carrying with it a pain that will be etched for years to come”, said the son of Ali Barakat who was killed while plowing his land in Kafr Nouran village west of Aleppo Governorate, controlled by Hayat Tahrir ash-Sham.

Salem (15 years old) described his father – as he flipped through his photos on his mobile phone with a sad expression on his face, said, “He wasn’t just a father, he was a friend who was full of kindness and compassion,” recalling the moments of happiness that filled his younger siblings when their father entered the house. On 11 March 2024, Barakat was harvesting his land when a “suicide drone” targeted him and threw him “more than twenty meters away,” killing him and destroying his tractor, according to his son, who from that moment on became the breadwinner for a family of six, bearing the burden of securing their monthly needs.

The Syrian Response Coordination team documented 256 drone attacks since the beginning of 2024 until 25 October in the same year, which killed 34 civilians and injured 88 others, including women and children.

This investigation sheds light on the development of drones by the Syrian regime and its affiliated militias, turning them into “suicide” aircraft loaded with war shells, and then testing them on civilians in opposition areas in northwestern Syria, especially farmers close to the contact lines, in an escalating trend since the beginning of 2024.

The investigation relies on testimonies of survivors of drone attacks or relatives of victims who died in those attacks, opinions of military experts, and analysis of the mechanism of manufacturing these drones, their development stages, and the parties responsible for that, relying on open sources.

Why this weapon!?

The regime forces and their affiliated militias have relied on “suicide drones” in their attacks against civilians in areas controlled by the opposition and Hayat Tahrir ash-Sham in northwestern Syria, as a “less expensive” alternative to conventional weapons, such as artillery and tank shells.

Maher al-Ahmad, a military expert and worker in the ranks of the Syrian National Army (opposition) said:

The price of a Gvozdika artillery shell reaches three thousand US dollars, while the cost of purchasing and developing a drone is estimated at about 350 dollars, not to mention its ability to track the target and achieve a direct hit, given its reliance on wireless guidance and the accurate image that covers a clear vision for the drone operator.

FPV aircraft, short for First Person View, have a first-person view, meaning that the operator of the aircraft sees everything that the drone’s camera can see as if he were inside it. They were manufactured by the Chinese company DJI in 2013. They are intended for photography enthusiasts and are used to track sports competitions and in video games for children and adults. They do not have an automatic pilot and operate without a global positioning system (GPS), according to the Arab Forum for Defence and Armament, an unofficial website run by a group of academics and specialists with the aim of spreading the culture of military thought.

Suicide drones rely on determining their targets and carrying out their attacks on other drones whose mission is monitoring and reconnaissance, of the Orlan 10 type, which are Russian-made and are used for search, reconnaissance and adjusting fire, through what they send to operations rooms, so that the targets that the “drones” should attack are determined, in addition to documenting the attack.

Destroying Livelihoods

In the fall of 2023, Hassan al-Sayyad was able to return to his land in the town of az-Ziyara in al-Ghab Plain, in the western Hama countryside, which is under the control of the opposition and close to the contact line, four years after he fled it due to the regime and its allies’ bombing of the town. Immediately upon his return, he planted wheat on his land and continued to visit it to check on his crops.

In early 2024, al-Sayyad went with his children to weed his land (remove weeds), and signs of joy were evident on their faces, but they were attacked by a “suicide drone” launched by regime forces in Jourin camp, which injured him and his children with varying degrees of severity, as his brother said. This is the first suicide drone operation against a civilian target in northwestern Syria, according to the investigation team’s monitoring.

Jourin camp is four kilometres away from az-Ziyara town and is used by regime forces and their allies as a headquarters for their ground operations, a base for artillery and tanks, and a control point for suicide and conventional drones.

Regime forces have reused suicide drones with a range of more than seven kilometres, when they targeted Qastoun town in al-Ghab Plain area in the western Hama countryside. At that time, the drones destroyed three cars, including the car of Hussein al-Qarqouri, one of the town’s well-known farmers.

On 22 February 2024, al-Qarqouri was with his workers on the land when they heard the roar of a plane in the sky. He asked the farmers to lie down on the ground, “and within seconds, a drone carrying an explosive shell entered the car window and exploded inside it,” he said.

Since that day, al-Qarqouri has not been safe from his children going to his land and working on it, for fear of repeating the incident, which he will never forget, saying: “I can’t help but think about how death was close to me, even though I am just a farmer clinging to my land to reap its benefits,” but “I no longer care about the land for fear of being targeted, which led to its damage due to my absence,” he said.

“We planted our land with wheat, lentils, clover and various types of vegetables after we returned to it,” and “perhaps the regime is deliberately displacing us from it again and forcing us to flee to the camps where life is miserable,” Al-Qarqouri added.

An X account (formerly Twitter), which publishes on behalf of the Russian forces, posted a tweet with a video attached, claiming that it documents the moment the regime targeted “terrorists” in Idlib with an FPV drone, but according to testimonies obtained by the investigation’s authors, the targets targeted were in al-Ghab Plain area in the western Hama countryside, and they were civilian targets, including Al-Qarqouri’s car.

After the video was analysed and matched with several sources and verification tools including InVID-WeVerify, Google Maps, and a special tour of the investigation team’s cameras in the targeted location, it became clear that the video is real, and that the investigation team findings are correct, which means that the regime documented the bombing of civilians itself, claiming that they were “terrorists.”

Two shots from the video published on X (formerly Twitter) show Hussein Al-Qarqouri’s car being targeted with an FPV suicide drone in Qastoun town in the western Hama countryside.

On the other hand, the investigators determined the coordinates of the place in a field visit to the location where Al-Qarqouri was targeted, and they match the video published by the regime and Russian media.

In another incident, Hussein Barakat’s car, loaded with women’s accessories, was destroyed and he lost what was inside it, after it was targeted by a suicide drone on 10 July, in Farkia village in Jabal az-Zawiya, south of Idlib.

Barakat, who works in the field of distributing accessories, had his car as his only source of income, which secures the expenses of his family of six. With its loss, he lost his source of income and was no longer able to provide for his family.

Surveillance cameras in Farkia village documented the moment Barakat’s car exploded, and it was later revealed that the explosion was caused by an FPV drone, which the regime uses in its attacks against civilians.

The regime and its allies have used several drones in each drone attack, and are trying to launch attacks at different times, focusing on one area, in conjunction with the flight of Russian reconnaissance aircraft, as was the case in the city of Darat Izza in the western countryside of Aleppo, when two drones targeted the family of Muhammad Qanawati, who was displaced from Aleppo city, on 16 April 2024, resulting in serious injuries to the father, mother, and their two children, according to military expert and defected officer Amer Al-Hawad. .

The attack on Qanawati family was part of an attack by five suicide drones, two of which targeted Qanawati’s car, while three targeted the city’s market without causing any civilian casualties.

Also, al-Nayrab town in the eastern Idlib countryside was attacked by seven suicide drones at once on 9 July 2024, targeting civilian vehicles and agricultural machinery, while farmers were working in fig and olive orchards.

A surveillance camera in the town documented the targeting of the car of Mahmoud Ahmed Al-Ali, a farmer and employee of the town’s water authority, and his son was accompanying him at the time, which led to damage to the car and the father and son miraculously survived, as al-Ali said, and it turned out that he was attacked by a suicide drone. On 21 July 2024, the town was attacked by 12 suicide drones, targeting a bread transport vehicle, a water well drilling machine, and agricultural machinery, which led to the displacement of a number of the town’s residents to border camps, according to Muhammad Abu Abdo, a resident of the town.

A video clip circulated on social media documented the drone attack on a well drilling rig around the town of Al-Nayrab, where its hissing was heard before it pounced on the drilling rig, and the damage was limited to material.

On the morning of that day, Fadi al-Taher and his colleague Karim al-Alo were sleeping near the excavator when the drone began to hover nearby. Al-Taher woke up to the sound of the drone, and when he looked around, he saw it was loaded with a shell. He quickly woke up Al-Alo, who was sleeping in the excavator’s trailer, as he testified to the investigation team.

Al-Taher and Al-Alo survived, but the excavator, “which was our only source of income, was damaged.” Without work, “we cannot buy our children’s needs, and the farmers will also be harmed, as they rely on us to dig irrigation wells in the area,” according to Al-Taher.

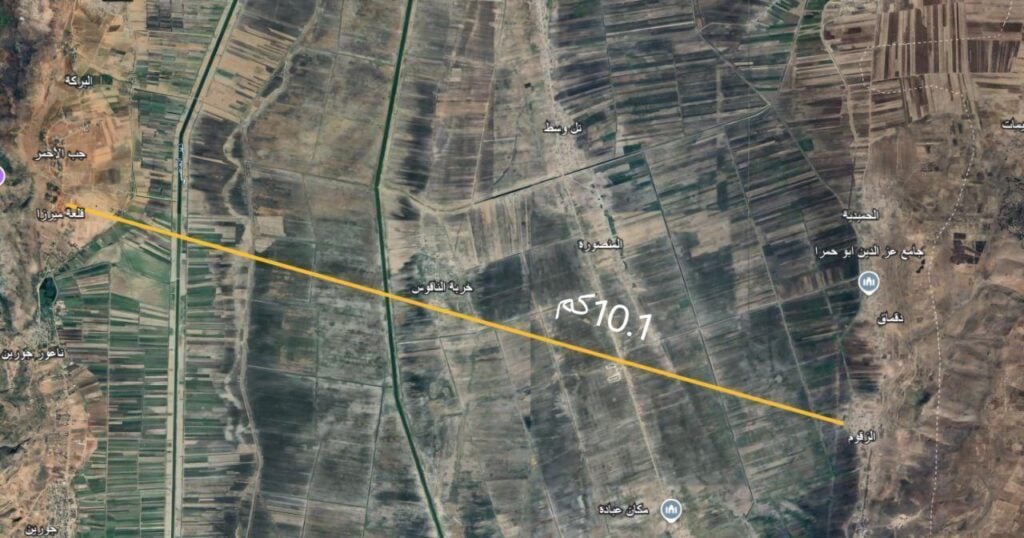

On 6 August 2024, the regime launched an attack with eight suicide drones, starting from the Jourin camp in al-Ghab Plain, targeting az-Zaqoum, al-Dakmaq, and al-Hamidiyah villages, and Qastoun town, resulting in the injury of one civilian and the destruction of five agricultural vehicles.

Notably, in this attack, three drones reached distances of more than ten kilometres, indicating a development in the drones and their equipment, enabling them to reach az-Zaqoum village and achieve a direct hit.

An aerial image shows the distance between the launch site of the FPV suicide drone in Jourin camp and its impact point in az-Zaqoum village in al-Ghab Plain.

A resident of az-Zaqoum village captured the moment of an explosion in his village, which was later revealed to be a suicide drone attack on a car in the town. Bashar Khaled al-Jassem was injured in the incident. Meanwhile, the regime claimed that the drone had targeted a terrorist headquarters and destroyed their equipment in al-Ghab Plain.

Al-Jassem detailed the incident in an audio interview with the investigation team, saying, “While I was preparing my brother’s car to go graze the sheep, a drone loaded with a rocket shell attacked us. It approached us quickly, then collided with the car and exploded, and I was hit by several shrapnel, one of which reached my liver.”

“The car is our only means, and without it, we cannot resume our work, because we transport the sheep to the pastures and transport the milk to sell in the markets,” he added. After the drone destroyed it, we lost our source of income

Bashar Khaled al-Jassem is currently receiving treatment in a hospital in northwestern Syria after being injured in an FPV suicide drone attack. The investigation team.

On the same day, seven kilometres away, a suicide drone attacked the car of farmer Suleiman al-Hussein, which was parked in front of his house. The explosion was heard throughout the entire Qastoun village, as al-Hussein told the investigation team.

Al-Hussein was fortunate that all 14 members of his family were inside the house at the time. “If any of them had been outside, they would have been killed,” he said. He added, “My car, which was destroyed, was my most valuable possession. I used it to go to the fields and it helped me in my work. With its destruction, we lost everything.”

The regime, through its repeated drone attacks on civilian targets near the front lines, seeks to “displace the population from their homes and lands,” according to Abdulrahman Ahmed, director of the Documentation Office in Hama. He noted that “68% of the attacks targeted farmers while they were working in their fields.”

From the danger of drones to poverty

The escalation of attacks against farmers has forced dozens of families to abandon their lands and fields before harvesting their crops, in a new wave of displacement that forces them to return to the border camps with Turkey. This is the case for farmer Mahdia al-Jandoub, who hails from Jabal az-Zawiya region south of Idlib and is a mother of four.

While sewing a piece of cloth in the al-Karama camps on the Syrian-Turkish border, al-Jandoub said:

In 2021, I left the camps and returned to cultivate my land despite all the challenges. Over three years, I harvested the crop and made a profit from it. I used some of it to repair my house, which was destroyed in the bombing of the Jabal az-Zawiya region.

She added:

In 2024, we were attacked by drones several times. One of these attacks was near us while we were working in the field. Due to the repeated attacks, I left the land and returned to the camp again to save my life and the lives of my children, the oldest of whom is 17 years old.

“We were living off the land that my husband left us before he was killed in an airstrike by the regime in 2018,” al-Jandoub said, recalling her husband’s last words to her about “the children and taking care of them.” Therefore, “I will endure poverty and hunger rather than risk their lives.”

Mahdia al-Jandoub inside her tent in al-Karama camp on the Syrian-Turkish border, (the investigation team).

Al-Jandoub embodies the suffering of many Syrians who have been experiencing a worsening poverty and hunger crisis in recent years. Figures indicate that the poverty rate has risen to 91.16% and hunger to 40.90%, according to a report issued by the Syria Response Coordinators in July.

In a letter sent by the UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, to the seventh annual Brussels conference in support of the future of Syria last year, he stated that nine out of ten Syrians live below the poverty line, and that more than 15 million Syrians, or 70% of the total population, need humanitarian aid.

Activist Ahmed Al-Ali says that the regime forces have entered a race to develop weapons, especially those with long-range guidance such as drones, but those forces have made their target defenceless civilians, including children, women and the elderly, contrary to the development plans followed by the armies of countries, as the Assad regime has used these weapons as a retaliatory operation against civilians in areas outside its control.

In response to this escalation, the international community’s response to suicide drones was timid, as reactions were limited to condemnation and denunciation, responses that directly or indirectly contributed to deepening the suffering of Syrians, which has extended for more than thirteen years.

In this context, the British Foreign Office condemned the Syrian regime’s attacks against civilians in northwestern Syria using suicide drones, emphasizing through the account of the UK’s Special Representative in Syria on the X platform (formerly Twitter) the need to “hold the perpetrators of these crimes accountable.”

While many farmers left their lands near the front lines, Walaa al-Jassem clung to her land in al-Ghab Plain in western rural Hama, continuing to cultivate and care for her five-dunam plot to provide for her family, as she told the investigation team.

Al-Jassem, a mother of seven, works with her daughters in the fields, said: “with the sunrise, I go with my daughters to pick vegetables, tomatoes, cucumbers, or beans, or to weed the land.” She added, “Our eyes are sometimes on our work in the field and sometimes in the sky from the west, where the regime’s areas of control are, fearing that they will bomb us with their drones”.

Development for More Victims

Opposition factions and some civilians have shot down suicide drones using hunting weapons, and some have fallen on their own. The signs, manufacturing process, and shape of these drones indicate that they are of the FPV type, an abbreviation for First Person View. This technology allows the user to see what the drone’s four-engine camera captures in real time. It has later evolved to use VR (virtual reality) glasses, allowing the operator to have an exciting and thrilling flying experience, in addition to performing acrobatic manoeuvres with ease, according to the drone weapons expert Muhammad al-Ali, who works with the Syrian National Army) affiliated with the Syrian opposition. (.

The cost of manufacturing each drone reaches $315. The cost of a four-armed frame made of carbon fiber or reinforced aluminum sheets does not exceed $10, and the control and guidance circuit and signal receiver (Autopilot) costs $80. The FPV video camera and transmitter cost $50, and four engines cost $160. The battery, which is sufficient for short distances, costs $15, in addition to the explosive payload weighing three kilograms, whose cost varies depending on its type and the manufacturing military entity.

In northwestern Syria, it was found through the wreckage of several downed drones and others stuck in tree branches that the warhead is similar to an RPG but smaller and has a greater destructive power. In the town of Qastoun, it penetrated the roof of a house, and in al-Nireb, it penetrated the iron of an excavator, which is about 7 mm thick, and in Qastoun, it penetrated the iron of a pickup truck, which is a strong type used for loading goods.

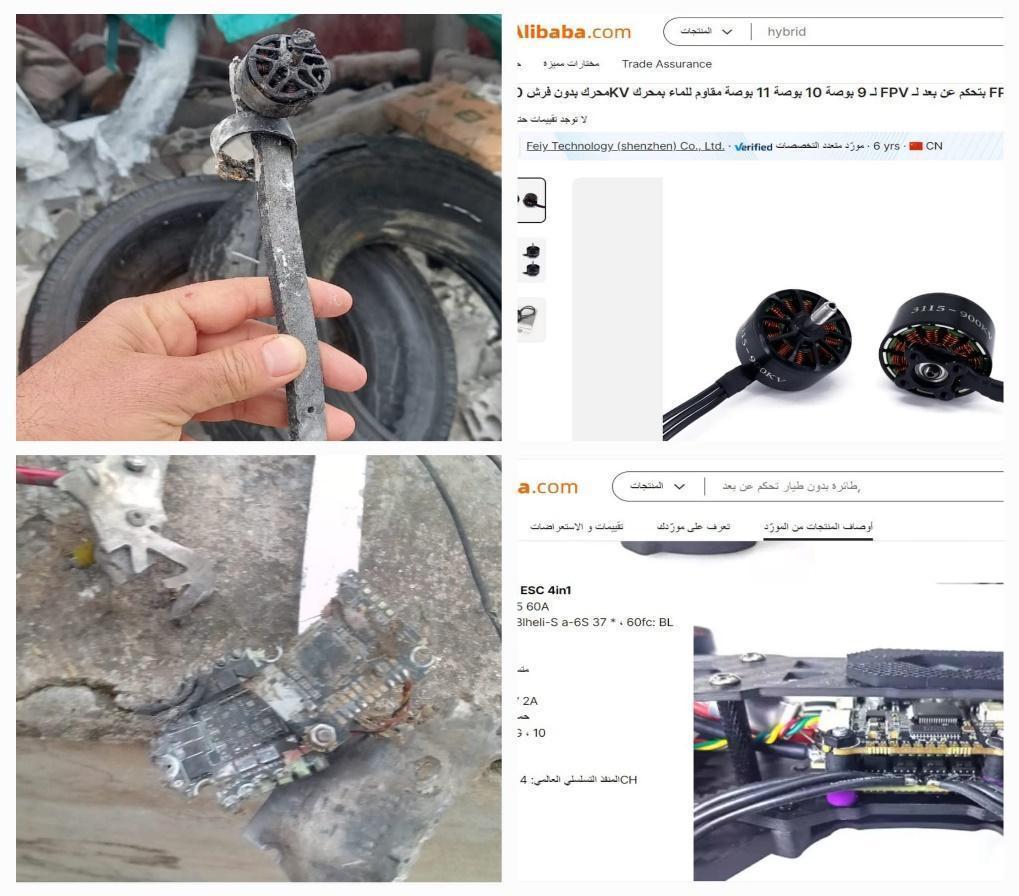

Based on a reverse image search on Google, it was found that the images of the downed suicide drones match similar images of the same drones published on an online store called Alibaba, which displays the technical specifications of the drone and its estimated price of about $300. The images of the accessories displayed on the mentioned site match the accessories contained in the remnants of the suicide drones in northwestern Syria. However, some of the downed suicide drones or their remnants indicate a significant modification to the main carrier of the drone, so that there are two models of suicide drones that attack civilians.

Abdul-Mehymin al-Shaghouri, owner of an electronics store that sells drones in Idlib Governorate, says, “FPV drones and their equipment are available for purchase through online stores, including Alibaba. Many shops owners’ resort to buying from the aforementioned site and receiving the goods in any country in the world, as they are displayed on the digital space, on the one hand, and their display is for civilian purposes on the other hand.”

The Assad regime and its allies have used two models of FPV drones in their attacks on civilians, their homes, and their cars. The first was with a carbon frame, which is the original body of the drone, and is always used for close-range attacks under 4 km. The second model has a locally made aluminum frame, on which the electronic components and the missile are mounted, and is used for long-range attacks over 8 km.

Carbon Model: Remnants of FPV drones with carbon frames have been found near the frontlines, such as Nireb east of Idlib and Mantif, Sarja, and Kafr Latta south of it. These villages are all within a 3 km radius of launch points belonging to the operations and command centers in Tal Mardikh, Tarnaba, and Saraqib. This is the original, unmodified model of the drone.

Image below: A visual comparison shows a match between an advertisement for Chinese FPV drones on the Alibaba shopping site and a drone that crashed in Mantif village in Ariha area on 15 July 2024, indicating they originated from the same manufacturer.

Aluminum Model: The investigation team documented remnants of FPV drones with aluminum frames, equipped with larger engines on the four wings and a larger battery compared to the original carbon model. These drones have a greater destructive capacity. This model has been spotted in towns like Qastoun, az-Zaqoum, ad-Daqmaq, al-Hamidiyah, and al-Qarqour, west of Hama, and Darat Izza, west of Aleppo, which are more than 9 km away from launch points linked to the operations rooms of the Jourin camp west of Hama and the Anjara camp west of Aleppo.

Drone expert Muhammad al-Ali attributes the aluminum model to experimentation and development efforts aimed at increasing the drone’s range, endurance, and payload capacity. The Assad regime and Russian forces have been working since 2023 to manufacture aluminum frames and increase battery capacity in research centers near Tal Qurtal south of Hama and the scientific research center in Masyaf, which has been targeted by Israel multiple times. According to Israeli media and a well-informed source cited by Al-Quds Al-Arabi, these attacks aimed to limit the development of weapons by Iranian militias and the Syrian regime.

The regime forces and their Russian and Iranian allies have adopted a time-varying and geographically variable attack method using suicide drones, according to military observer Abu Amin, who preferred not to give his real name for security reasons. The suicide drone attacks are distributed between the areas of al-Ghab Plain west of Hama, Ariha area south of Idlib, Sarmin east of it, and al-Atarib area west of Aleppo.

The regime forces move the attacks from one area to another with a time interval of no less than 10 days, with the aim of giving the residents a period of time to return to their normal lives somewhat and lower their level of caution, so that they can be attacked again and repeatedly at intervals of time to achieve the greatest number of casualties among the population.

Abu Amin, who works in monitoring regime warplanes, Russian aircraft, and military movements in northwestern Syria, adds: “The longest distance covered by the FPV suicide drones is 9,200 km in al-Qarqour village in al-Ghab Plain west of Hama, when the aircraft targeted a fishermen’s room, and the village of Sarjah in the Ariha area when targeting a civilian communications tower on a public water tank.”

Conclusion

The Assad regime has exploited military research centers to develop weapons for use against civilians, and has converted educational centers such as the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Hama, affiliated with Al-Baath University in Homs, into a military center for this purpose.

The attacks with suicide drones contributed to new waves of displacement of the population at the time towards the camps, which resulted in high rates of unemployment and poverty, coinciding with the failure of the international community at the time to stop these attacks and its contentment with the position of the spectator.

Since the beginning of 2024, the regime forces and their allies have followed the approach of testing suicide drones on the bodies of Syrians close to the contact lines at the time, according to Lieutenant Colonel “ Haitham Dahman” in the National Army, as the attacks varied from one region to another using the same weapon with different models, as Russia turned the Syrians into a testing ground for developing the weapons it used in its invasion of Ukraine.

Developing and testing weapons on Syrians was not new to Russia, as the Russian forces worked to develop the Kornet guided missile weapon in 2021 and developed its destructive capabilities and target distance from 5.5 km to 9 km, according to an investigation by Al-Arabi Al-Jaded, preceded by an explicit admission by Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu, in the summer of 2021, saying that his country’s army had tested more than 320 different types of weapons during its operations in Syria.

The increase in attacks on civilians and their agricultural lands, through suicide drones, has destroyed their livelihoods and new stability projects for returnees to their homes, especially with the destruction of means of production, such as agricultural machinery and cars.

In recent years, the regime government has always promoted its efforts to achieve stability projects and livelihoods, and has begged the international community to help it,” while at the same time “the regime uses suicide drones to violate the Syrians’ right to life and gives them two choices: either die on their land or be displaced to live in camps.

This investigation is part of a project implemented by the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression and was published on Jesr Press website on January 24, 2025.