Human Rights Council

Thirty-sixth session

11-29 September 2017

Agenda item 4

Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention

Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic*

Summary

Violence throughout the Syrian Arab Republic continues to be waged in blatant violation of basic international humanitarian and human rights law principles, primarily affecting civilians countrywide. During the reporting period, warring parties continued to lay sieges and instrumentalized humanitarian aid in order to erode the viability of civilian support bases and compel surrender. Local truces in Fu’ah and Kafraya, northern Idlib, in Madaya, Damascus countryside, and in Barza, Qabun and Tishreen, eastern Damascus, incorporated evacuation agreements resulting in the forced displacement of civilians from those areas.

Terrorist groups Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), and armed group fighters targeted religious minorities through car and suicide bombings, the use of snipers and hostage-taking. Among the most vulnerable were internally displaced persons and children. Nowhere was this more evident than in Al-Rashidin, Aleppo, where a car bomb targeted displaced civilians from previously besieged Fu’ah and Kafraya — two predominantly Shia Muslim towns — killing 96 persons, including 68 children.

Government forces continued the pattern of using chemical weapons against civilians in opposition-held areas. In the gravest incident, the Syrian air force used sarin in Khan Shaykhun, Idlib, killing dozens, the majority of whom were women and children. In Idlib, Hamah, and eastern Ghouta, Damascus, Syrian forces used weaponized chlorine. Syrian and/or Russian forces continued to target hospitals and medical personnel.

The Commission is gravely concerned about the impact of international coalition air strikes on civilians. In Al-Jinah, Aleppo, forces of the United States of America failed to take all feasible precautions to protect civilians and civilian objects when attacking a mosque, in violation of international humanitarian law. In Ar-Raqqah, the ongoing Syrian Democratic Forces and international coalition offensive to repel ISIL has displaced over 190,000 persons, and coalition air strikes have reportedly resulted in significant numbers of civilians killed and injured. Investigations are ongoing.

* The annexes to the present report are circulated as received, in the language of submission only.

Contents

- Introduction

- Political and military developments.

III. Attacks against the civilian population

- Sieges.

- Targeting and hostage-taking of religious minorities

- Impact of the conflict on children

- Attacks against protected objects

- Places of worship

- Medical facilities

- Use of chemical weapons

VII. Ongoing investigations

VIII. Conclusions.

- Recommendations

Annexes

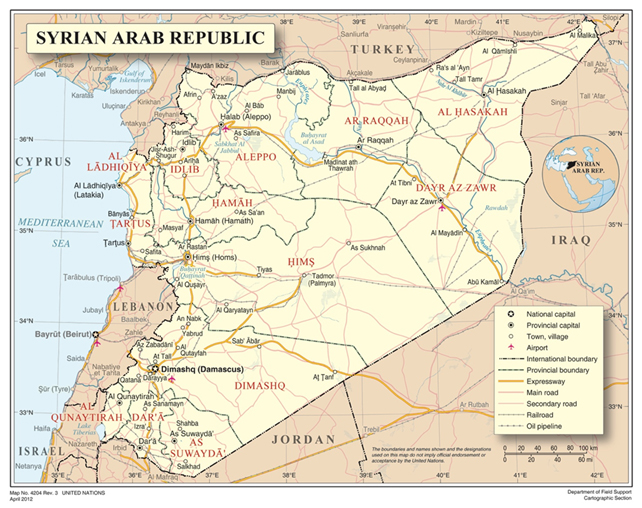

- Map of the Syrian Arab Republic

- Inquiry into allegations of chemical weapons used in Khan Shaykhun, Idlib, on 4 April 2017.

III. Life under siege and truces

- Introduction

- In the present report, submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 34/26, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic presents its findings based on investigations conducted from 1 March 2017 to 7 July 2017.[1]

- The methodology employed by the Commission was based on best practices of commissions of inquiry and fact-finding missions.

- The information contained herein is based on 339 interviews conducted in the region and from Geneva.

- The Commission collected, reviewed and analysed satellite imagery, photographs, videos and medical records. Communications from non-governmental organizations and Governments were consulted, as were United Nations reports.

- The standard of proof was met when the Commission obtained a reliable body of information to conclude that there were reasonable grounds to believe the incidents occurred as described, and that violations were committed by the warring party identified.

- The Commission’s investigations remain curtailed by the denial of access to the Syrian Arab Republic.

- Political and military developments

- During the reporting period, the pace of both political and military developments notably increased. As a result, two distinct dynamics emerged: one in the west of the country, under the de-escalation agreement concluded as part of the Astana talks on 4 May by its three guarantors (Iran (Islamic Republic of), the Russian Federation and Turkey), and the second in the central and eastern parts of the country, where Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) continues to rapidly lose significant swaths of territory. Levels of armed violence decreased in some locations under the de-escalation agreement, including in Idlib, western Aleppo and, more recently, in the southern province of Dar’a. The situation remains volatile, however, in the remaining two zones of eastern Damascus and northern Homs. Beyond the de-escalation zones, civilians, in particular internally displaced persons, in territories held or previously held by ISIL are witnessing increased violence as actors scramble to establish control over those areas.

- In early July, a fifth round of talks was held in Astana to agree upon implementation modalities covering the de-escalation zones and upon monitoring mechanisms that could involve potential deployment, by the three guarantors, of police or military forces. While neither the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic nor the opposition signed the Astana agreement, the latter remain adamantly opposed to deployment of Iranian forces for monitoring purposes. Technical committees, formed as part of the agreement, continue to discuss the implementation and another round of discussions is expected in early August. During the next round, those modalities will need to be specified and implemented with support from the guarantors. Previous ceasefire agreements have demonstrated that a lack of enforcement mechanisms increases the likelihood of relapse towards prior levels of violence.

- The Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria, Staffan de Mistura, who attended the latest round of Astana talks, has stressed that the Astana and Geneva processes were “mutually supported actions” with the same aim of supporting ceasefire efforts. The Special Envoy held two rounds of talks in May and July. During the May round, the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and the opposition agreed to discuss “four baskets” of issues, including political transition, constitutional reform, elections and combating terrorism. The latest round of intra-Syrian talks concluded in Geneva on 15 July. Despite persistent efforts by the Special Envoy, direct talks did not take place, and the rift in positions among parties remains wide. The Government of the Syrian Arab Republic insists on addressing the issue of combating terrorism before any discussion on transition takes place, while the opposition prioritizes discussing a political transition as stipulated in Security Council resolution 2254 (2015). An eighth round of Geneva talks is slated for September.

- On 7 July, a ceasefire agreement was brokered between the Russian Federation and the United States of America covering the southern provinces of Dar’a, Qunaytirah and Suwayda’. The agreement is aimed at securing humanitarian access and includes a monitoring centre to record ceasefire breaches. Hostilities have already markedly decreased in these three governorates since the agreement took effect.

- While the Astana and Geneva tracks have achieved some progress, a lack of effective enforcement mechanisms and an absence of a wider agreement on priorities within the larger political framework among parties render this progress tenuous. The Commission has consistently called for an inclusive political process and for a nationwide ceasefire beyond localized agreements.

- Militarily, front lines in the western area of the Syrian Arab Republic, and particularly those around de-escalation zones in Dar’a, Idlib, eastern Damascus and northern Homs, have generally remained static. In northern Hamah, however, government forces and affiliated militias have, since April, intensified attempts to regain control of the “strategic triangle” area comprising Kafr Zeita, Murek and Al-Latamneh. Attempts to advance on the ground were accompanied by extensive air strikes on these locations, and also on adjacent southern Idlib, where the Khan Shaykhun chemical weapons attack occurred on 4 April.[2] Control over this triangle would result in forces of the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and affiliated militias gaining a strategic foothold over armed groups in Idlib.

- A combination of factors in Idlib, including increased concentrations of internally displaced persons and infighting among various armed groups, has placed the civilian population under substantially increased risk of violence. Episodes of infighting have markedly intensified over the past three months, pitting Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, an umbrella of extremist factions led by the terrorist group Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (formerly known as Jabhat al-Nusra), against Ahrar al-Sham and other affiliates. Both coalitions have vied for control over parts of Idlib through direct clashes, kidnappings and assassinations. The two coalitions also compete to recruit new fighters into their ranks, including evacuees from previously besieged areas. Displaced civilian actors, including members of local councils and activists, also face increased threats and arrests, particularly by members of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, for their dissident activities. While air strikes in Idlib have decreased, the Commission remains extremely concerned about the internal situation in the governorate as the scope and intensity of infighting increases in areas where an estimated one million internally displaced persons subsist without adequate humanitarian assistance.

- Moreover, the majority of internally displaced persons in areas controlled by the Government, armed groups or terrorists continue to face difficulties accessing humanitarian assistance due to a diversion of and lack of access to aid. In some areas, the impact of unilateral sanctions has further weakened the ability of humanitarian actors to deliver, owing to increased prices and reduction in the availability of crucial items in local markets.

- In contrast to the western part of the country, front lines elsewhere have changed drastically over the past three months. Outside the de-escalation zones, the forces of the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and affiliated militias deployed fighters to overtake vast swaths of territory from ISIL, namely in the centre and east of the country and, most notably, in Aleppo, Homs and Ar-Raqqah, and reaching the eastern edges of Dayr el-Zawr Governorate. Newly recaptured territory extends to strategic portions of the Iraqi-Syrian border. In this context, on 18 May and 6 June, air strikes by the United States hit a convoy of pro-Government forces in the strategic Tanf region across the Jordanian and Iraqi borders, potentially escalating tensions in this highly contested area.

- The past few months have also witnessed significant advances by the Syrian Democratic Forces against ISIL in Ar-Raqqah, the terrorist group’s self-proclaimed capital city. The Syrian Democratic Forces, comprising Kurdish forces, namely the People’s Protection Units (YPG), alongside affiliated groups, including the Free Syrian Army and tribal elements, have gained control over portions of Ar-Raqqah city and are effectively besieging it. Tens of thousands of civilians are reportedly trapped as street-to-street battles between the Syrian Democratic Forces and ISIL continue to intensify. Nearly 200,000 internally displaced persons have fled the city towards territory controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces. The Commission is concerned about the fate of 50,000 to 60,000 civilians who remain trapped in Ar-Raqqah city.

- While the de-escalation agreement in Astana has resulted in some reduction in violence, the Syrian conflict remains highly fragmented as distinct dynamics evolve in various parts of the country. The increasing involvement of external actors, while creating some opportunities for localized peace, also bears the seeds of discord as these actors have diametrically opposed objectives. These objectives are often connected to broader regional or international interests — far from the interests of the Syrian people, which should prevail in the process of ending the conflict and building peace.

III. Attacks against the civilian population

- Sieges

- Use of siege warfare has affected civilians more tragically than any other tactic employed by warring parties in the conflict. Presently over 600,000 Syrian men, women and children countrywide remain trapped in besieged locations, often in the most dire conditions. During the period under review, warring parties continued to lay siege to encircled communities and instrumentalize humanitarian aid deliveries to trapped civilians in order to compel surrender in Damascus, Rif Damascus, Dayr el-Zawr, Homs and Idlib Governorates. These sieges are characterized by the routine denial of delivery of vital foodstuffs, health items and other essential supplies to besieged enclaves, as well as indiscriminate attacks and deliberate attacks targeting civilian infrastructure, including hospitals, in order to erode the viability of life under the control of opposing sides. Such tactics result in the denial of the rights to freedom of movement, adequate food, access to education and access to health care, and, in many instances, the right to life.

- Some sieges ended during the reporting period as a result of local truces that included evacuation agreements (discussed further below). For example, an agreement initially negotiated in September 2015, known as the Four Towns Agreement, was implemented beginning in April 2017, concerning Madaya and Zabadani, in Rif Damascus, and Fu’ah and Kafraya, in Idlib. Negotiations for the Four Towns Agreement took place with armed groups and under the aegis of third States, which assisted in brokering it. Similarly, in May, pro-Government officials and mediators on one side, and armed group members and/or local council representatives on the other, negotiated and implemented truces in Barza, Tishreen and Qabun, in eastern Damascus. Siege conditions endured by civilians in these localities are summarized in annex III, along with details on negotiations and stipulations within these agreements. All truces mentioned above have incorporated evacuation agreements, which has led to the forced displacement of thousands of civilians from those areas.

- Government reconciliation

- After hostilities fully ceased and truces were implemented in the four towns and in Barza, Tishreen and Qabun, pro-Government forces required certain individuals from the previously besieged areas to undergo a reconciliation process as a condition to remain, while others were not given the opportunity to reconcile. Legislative Decree No. 15 of July 2016 serves as the basis for reconciliation, and includes amnesty for all individuals who turn themselves in and lay down their weapons, including fugitives. These individuals have generally included fighters and civilians wanted for defecting or deserting.

- In effect, the reconciliation process allowed government forces to categorize populations on the basis of allegiance, by filtering fighting-age males, generally aged 18 to 45 years, into two categories: armed group members and wanted individuals who cannot stay in the locality and risk detention if they do, and those who agree to pledge loyalty to the Government. The latter group are permitted to stay but are forcibly conscripted into either local units under the umbrella of the National Defence Forces or into a paramilitary force, or sent to front lines as part of the Syrian army after a six-month notice period. In Barza, some fighting-age males were reportedly conscripted into a local unit called the “Nation’s Castle” within 15 days.

- Not all civilians were offered the option to reconcile, however. In Madaya, no reconciliation was offered to health-care personnel because of their medical work. Civilians able to remain in Madaya were required to fingerprint statements of loyalty to the Government, while others also underwent background checks. Similarly, in Barza, civilians explained that those unable to reconcile included members of the local council, relief workers, activists and family members of fighters. Civilians in Barza who were able to reconcile submitted to the same procedure as was implemented in Madaya. Civilians in these localities further spoke of lists of individuals who were not offered reconciliation due to their sympathy with opposition groups. As such, the reconciliation process has induced the displacement of both fighters and groups of dissident civilians in the form of organized evacuations.

- Evacuation agreements and forced displacement

- Agreements between pro-Government forces and armed groups concerning the four towns (brokered with the assistance of third States) and Barza, Tishreen and Qabun provided for the evacuations of set numbers of fighters and civilians. Parties to a non-international armed conflict may not order the displacement of the civilian population for reasons related to the conflict, unless the security of those civilians or imperative military reasons so demand.[3]

- The exception based on the security of civilians would be justified, for example, to prevent civilians from being exposed to grave danger. Displacement for humanitarian reasons is not permissible where the humanitarian crisis causing the displacement, such as starvation, is the result of a warring party’s own unlawful conduct.[4] Further, the humanitarian obligation to evacuate wounded and sick individuals from conflict areas exists at all times, and is therefore not limited to the period of evacuation under such agreements.[5] Similarly, the evacuation of civilians based on military necessity may not be justified by political motives.[6]

- On 14 April, 60 buses carrying an estimated 2,350 people from Madaya departed for the Ramouseh garage area in Aleppo city, after which they were transported to Idlib. Simultaneously, 75 buses carrying 5,000 people from Fu’ah and Kafraya departed towards Al-Rashidin in western Aleppo city (see paras. 39-43 below). On 19 April, another 11 buses carrying fighters and civilians from Madaya, Zabadani and neighbouring areas departed for Idlib, rendering Zabadani completely depopulated. On the same day, another 3,000 fighters and civilians evacuated Fu’ah and Kafraya towards Al-Rashidin.

- In eastern Damascus, three rounds of evacuations of fighters and civilians from Barza took place on 8, 12, and 20 May. In Tishreen, all fighters and civilians were evacuated on 12 May. In Qabun, two main rounds of evacuations were organized: the first on 14 May, which comprised 70 buses, and a subsequent round of 80 buses. The latter evacuations were followed by smaller rounds, comprising 20 buses each, on 15 May. Approximately 6,000 fighters and civilians left Qabun. The terms of the local truce were communicated to civilians on 12 May, giving them only a few days to evacuate.

- Government forces and armed groups have routinely denied humanitarian evacuations for wounded and sick civilians and fighters until surrender (truces) and subsequent evacuation, granting it only in rare instances when exchanges between the four towns were negotiated. Civilians in Qabun, for example, recalled using tunnels connecting Qabun to eastern Ghouta, Damascus, to evacuate the wounded, although infighting between rebel factions affected the regularity of tunnel access.

- Civilians interviewed by the Commission echoed how their decision to evacuate previously besieged areas was involuntary in nature and that they had accepted to leave because they “had no choice”. Women and children mostly followed their male heads of household. In Madaya, civilians emphasized that they did not want to abandon their land and property, but did not trust government forces enough to stay. Some women in Madaya, for example, described fear that their sons would be conscripted and a general distrust of government forces as their reasons for not reconciling. Other civilians recalled how the same fear that drove them to evacuate to Idlib also had an impact on their right to return. Those civilians feared reprisal violence or detention, noting they would not return to their homes even if given the option, with others having largely given up on the prospect. Still others had become aware that their homes had been looted or appropriated by pro-government forces.

- Similarly, in Kafraya, interviewees described how siege conditions had forced them to evacuate despite their desire to remain. One interviewee recalled watching her children become increasingly malnourished, while another noted increased attacks and outbreaks of preventable illness that had pushed civilians to leave. Interviewees in Kafraya also expressed doubt concerning their ability to return to their homes following evacuations.

- Often, local councils in opposition-held areas have entered into memorandums of understanding with armed groups in order to delineate responsibilities and affirm their capacities as elected officials of quasi-civil governance bodies. Despite this, neither political leaders, such as local council representatives, nor military commanders, such as pro-Government or armed group fighters, possess the requisite authority to consent to evacuation agreements on behalf of individual civilians.[7] Moreover, although some humanitarian organizations have participated in facilitating evacuations in varying capacities, including the Syrian Arab Red Crescent during the evacuations of Madaya and Tishreen, their participation does not render the underlying displacements lawful.[8]

- By evacuating to the border of Idlib Governorate civilians, including doctors, relief workers, activists, civil society staff and local council members, who are, or who are perceived to be, sympathetic to opposition factions, government forces are able to serve a calculated warring strategy: population transfers in this context remove both opposition actors and their supporters to a single area in the northwest area of the Syrian Arab Republic. Only those civilians who are offered the chance to pledge loyalty to the Government in the form of reconciliation may remain in their homes. Overall, the pattern of evacuations occurring throughout the country appears intended to engineer changes to the political demographies of previously besieged enclaves, by redrawing and consolidating bases of political support.

- As evinced by the 15 April attack on the convoy in Al-Rashidin (see paras. 39-43 below), evacuations are perilous and desperate journeys. Civilians evacuated from Madaya, Barza, Tishreen and Qabun were only able to carry modest possessions with them, were not evacuated to final destinations of their choice and were not provided with satisfactory conditions of shelter, hygiene, health, safety or nutrition either en route or once they reached Idlib.

- Some of those displaced from Madaya and Barza were initially accommodated in schools in Idlib, which were ill-prepared to receive them. Others later moved to overcrowded camps for internally displaced persons, or to towns in the Idlib countryside described by an evacuee as “desperate”. While civilians throughout Idlib Governorate continue to live under bombardment, suffer from a lack of aid and are exposed to the effects of increased armed group infighting (see para. 13 above), the final destinations of those transferred from Government-sympathetic Fu’ah and Kafraya were areas under Government control in Homs, Tartous and Latakia Governorates.

- Additionally, the Government has reportedly implemented legislative measures to dispossess dissenting populations of their property, and has raised legal and administrative measures to impede displaced persons from registering or retaining private property. Recently issued presidential decrees require in-person registration and contestation of land titles countrywide. Requirements to register land titles or contest ownership in person would render it virtually impossible for many internally displaced persons and refugees to protect their properties. The use of such legal and administrative tools may also be intended to pressure certain populations to reconcile, so as not to lose their property. Such measures may have the opposite effect, however, by further disenfranchising significant segments of the population, and complicating future efforts towards conflict resolution and, ultimately, reconciliation.

- For each civilian who was unable to freely decide on his or her movement or destination, the agreement to evacuate him or her amounts to an unlawful order. There is no indication that any of the evacuations satisfied the exceptions permitted on the basis of security of civilians or imperative military reasons. Therefore, the ordering of dissenting populations to evacuate Madaya and Barza, the general evacuation of Fu’ah and Kafraya, and the ordering of the entire civilian populations to evacuate Tishreen and Qabun constitute the war crime of forced displacement. The Commission has received conflicting information on the presence of civilians in Zabadani at the time of its evacuation.

- Targeting and hostage-taking of religious minorities

- Like government forces, armed groups have galvanized bases of support throughout the conflict, manifesting in heightened religious tensions and leading to violence with sectarian undertones carried out against civilians. The emergence of terrorist and extremist armed groups further fuelled such tensions. During the reporting period, terrorist and armed groups continued previously documented patterns of carrying out intentional attacks against civilians, many of them women and children, belonging to minority religious groups, and using other religious minorities as hostages.

- On 11 March, at midday, two explosions detonated near the Bab al-Saghir cemetery, a well-known Shia pilgrimage site south of the old city of Damascus. The explosions detonated 10 minutes apart in the parking lot of the cemetery, where buses transporting pilgrims were parked. The first explosion was set off by a passing bus. As ambulances arrived and first responders tended to victims, a suicide bomber killed more pilgrims and several rescuers.

- Overall, the two explosions killed 44 civilians, including 8 children, and injured another 120, leaving several women and children in critical condition. The majority of victims were Iraqi Shia pilgrims visiting Bab al-Saghir and the nearby Sayeda Zeinab shrine. Thirteen Syrians, mostly first responders, also died in the attack. The following day, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham claimed responsibility for the attack, claiming it was targeting Iranian militias and government forces. The Commission found no evidence to substantiate the claim.

- In the early hours of 14 April, evacuees from Fu’ah and Kafraya (see paras. 19 and 25 above), arrived in opposition-held Al-Rashidin on the outskirts of Government-held western Aleppo city. They remained there the following day while warring parties worked out disagreements among themselves. Evacuees recalled fearfully boarding buses prior to leaving Fu’ah and Kafraya after armed group members fired shots that injured two women.

- While waiting in Al-Rashidin, evacuees received very limited amounts of food so, when at around 3 p.m. someone began distributing snacks from a silver car, dozens of children gathered around the car. About a half an hour later, a blue pickup arrived and evacuees, mostly women and children, rushed to it believing it too would be bringing food. Instead, within seconds, the pickup exploded, killing at least 96 people, including 68 children and 13 women. Another 276 individuals were injured, including 42 children and 78 women, at least 1 of whom was pregnant. As people screamed and scattered around, some onlookers yelled sectarian insults at the Shia victims. A mother whose husband took their two sons to obtain food from the silver vehicle described rushing to the scene upon hearing the explosion, but she was forced by armed group fighters to return to the convoy. She subsequently learned that her 10-year-old son had died.

- Although the vast majority of casualties were evacuees from Fu’ah and Kafraya, at least 10 armed group fighters were also killed in Al-Rashidin. Casualties were taken to hospitals in Bab al-Hawa, Idlib; Atareb, Aleppo; Aqrabat, Idlib; Saraqeb, Idlib; and Thawed al-Kemnah, Aleppo. The remaining evacuees, however, were transported from Al-Rashidin to Jibreen, Aleppo, on the evening of 15 April, without knowing the whereabouts of their families. In Jibreen, evacuees provided the names of those missing to government authorities, and some of the injured have since been reunited with their families. At least 46 persons, including a 3-year-old boy, remain missing.

- While a number of those missing are likely still hospitalized, at least one group of 17 Shia individuals, including elderly persons and children, were taken hostage by armed group fighters immediately after receiving treatment in makeshift hospitals in western Aleppo. Some hostages were released after prolonged negotiations involving the swap of a high-ranking armed group leader, but at least 15 others, including one 4-year-old child, remain in captivity.

- No party has claimed responsibility for the attack in Al-Rashidin, and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and Ahrar al-Sham have explicitly denied involvement. While there is insufficient information from which to identify the perpetrator, there are significant indications to conclude the attack was carried out by armed group factions or fighters. Eyewitnesses reported seeing the blue pickup that detonated arrive from opposition-held territory, and the location of the convoy was under the control of a number of armed groups, including Nour al-Din al-Zenki (then part of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham), Ahrar al-Sham and Free Syrian Army groups. Further, vehicle borne improvised explosive devices have primarily been a modus operandi of extremist factions and some armed groups throughout the conflict. In view of the high number of civilian casualties, particularly among children, it is clear that Shia civilians from Fu’ah and Kafraya were the object of the attack, amounting to the war crime of intentional attacks against civilians.

- On 18 May, ISIL militants attacked the town of Aqarib al-Safiyah and attempted to attack nearby Al-Manbouja village in the Hamah countryside. Both areas were under Government control at the time, and located on the border of ISIL-held territory, close to Al-Salamyia — a strategic location for warring parties vying for control of Hamah. Aqarib al-Safiyah and Al-Manbouja are predominantly populated by Ismailis, a minority Shia Muslim community.

- Residents of Aqarib al-Safiyah awoke at 4 a.m. on 18 May to the sound of gunshots. As they attempted to flee, many were killed in the streets by ISIL snipers positioned at the village’s water reservoir and on the roofs of houses. At least two families were hiding in bedrooms when ISIL militants stormed their homes and shot them at close range; among the victims were a 4-month-old baby and an 11-year-old boy. In total, 52 civilians were killed, including 7 women and 12 children. Another 100 were injured, including 2 girls who suffered serious head wounds. The vast majority of victims were Ismaili Muslims. Survivors recalled being verbally insulted by ISIL fighters on account of their religious beliefs. During a similar attack on Al-Manbouja in 2015, ISIL militants killed up to 46 civilians, most of whom were also Ismaili Muslims.[9]

- Earlier this year, a group of hostages held by armed groups in Douma, in the Damascus countryside, for over three years was released in exchange for armed group fighters detained by government forces. On 11 December 2013, various armed groups, including Jaysh al-Islam and Ajnad al-Sham (currently part of the Faylaq ar-Rahman coalition) stormed the town of Adra al-Omaliyah in eastern Damascus. Numerous Alawite families, including young children, in addition to some Ismaili, Shia, Druze and Christian families, were ordered by fighters to stay in the basements of their apartment complexes, where they remained in de facto detention. Later, armed group members entered the basements to inquire about the backgrounds of male family members, at which point some civilians were intimidated, verbally assaulted and derogatorily referred to as “nusairis” by the fighters. Some of the civilians were informed five or six months later by armed group emirs that they would be “distributed” to different armed group factions, as they were considered war booty.

- At the next detention site, relocated hostages recounted how men were separated from women and children, although members of Ajnad al-Sham reunited families under their control “once or twice a month”. Detained women described overhearing the brutal torture of male detainees. One Alawite woman who managed to escape the events of 11 December 2013 in Adra al-Omaliyah was contacted in August 2014 by an armed group representative who presented himself as the head of the “office of hostages”. The man claimed that her husband had been moved to Douma and then facilitated contact between her and her husband. Over the course of the next two and half years, she was able to communicate briefly with her husband on five occasions via mobile telephone. On one occasion, her husband sent her a picture of himself, in which he appeared to be “half of his weight”. Released hostages echoed that Faylaq ar-Rahman routinely denied them food and medical care.

- Other hostages released in 2017 described how members of Ajnad al-Sham forced exhausted men to dig tunnels in besieged Douma for the groups to use as supply routes to eastern Ghouta (see para. 27 above). One woman recalled how her son was killed when government forces bombed out the tunnel he was digging in late August 2016. Some men were also forced to dig wells, while elderly men were exempt from labour. Up to 100 men from Adra al-Omaliyah belonging to minority religious groups remain in captivity as hostages, waiting to be swapped. Up to 175 women and children from Adra al-Omaliyah are still detained.

- Impact of the conflict on children

- Children throughout the Syrian Arab Republic remain disproportionally vulnerable to violence and abuse. The overwhelming impact of the conflict on civilians during the reporting period revealed that children remain victimized on multiple grounds, and continue to be denied the protection to which they are entitled under the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which the Syrian Arab Republic is party. Syrian children suffered as a consequence of attacks against civilians, lack of access to education, and their recruitment as child soldiers. For example, out of the 179 individuals killed during the chemical weapons attack in Khan Shaykhun and the suicide bombing in Al-Rashidin, 54 per cent of the deaths were of children.

- On 7 March, at approximately 9.20 a.m., aerial bombardments carried out by pro-Government forces struck a primary school complex in Autaya, eastern Damascus, while classes were in session. Eight female students were injured, one in second grade who suffered head injuries. Less than one month later, on 2 April, the primary school was struck again, although no children were harmed. While the primary school is still standing, parents in Autaya now refuse to send their children to school fearing further air strikes. After the 4 April sarin attack in Khan Shaykhun (see paras. 72-77 below and annex II), five schools were forced to shut down in the town, namely, Ahmel Talhan, Farouk al-Kang, Salh al-Dawadi, Adnan al-Malkwa and Tusuremm schools. Attacks against schools seriously violate the right to education and gravely undermine the future potential for Syrian children to participate fully in their communities.

- The Commission continues to receive numerous allegations of children being recruited, placed in training camps and, in some cases, sent to active front lines. In March, for example, one 14-year-old boy joined the Syrian Democratic Forces in Tal Abyad, Ar-Raqqah, without the consent of his parents. He had approached a Syrian Democratic Forces recruitment centre in Tal Abyad voluntarily, was accepted by authorities of the Forces, and was killed in combat in early June in Ar-Raqqah countryside. Representatives of the Syrian Democratic Forces communicated the news of the boy’s death to his family, but did not allow the family to bury him, instead burying him in a cemetery for “martyrs”. Numerous accounts of ISIL militants recruiting, training and using children in Ar-Raqqah also continue to be received.

- Attacks against protected objects

- Places of worship

- Beyond intentional attacks against religious minorities, incidental attacks against religious cultural property were carried out during the reporting period, undermining the ability of civilian communities to peacefully express their faiths. In one emblematic example, minutes before 7 p.m. on 16 March, a series of air strikes hit a building in a religious complex in Al-Jinah, killing 38 persons, including 1 woman and 5 boys. Three of the boys were aged between 6 and 13 years, 2 others were 17 years old. An additional 26 persons were injured, many of whom suffered from crushed limbs, head trauma and suffocation caused by structural collapse. First responders began a rescue operation immediately after the air strikes, and continued to retrieve bodies from under the rubble until the following morning.

- Al-Jinah, a village in western Aleppo countryside that closely borders Idlib Governorate, is controlled by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, Ahrar al-Sham and a number of local Free Syrian Army groups, among others. On 16 March, the United States Central Command issued a statement announcing that “US forces conducted an air strike on al-Qaeda (…) killing several terrorists” at a meeting location in Idlib.[10] It subsequently clarified that the statement referred to the Al-Jinah air strike. Over the following days, media outlets and non-governmental organizations reported that all casualties were civilians attending a religious lesson at the Omar Bin al-Khatab mosque, although the Pentagon denied hitting a mosque or killing civilians. The mosque is located approximately 1.5 kilometres from the centre of Al-Jinah, between Al-Jinah and Ibeen. The air strikes were carried out by United States forces in their capacity as a member of the international coalition.

- On 7 June, the United States Central Command presented a summary of its post-investigation findings on the incident, including interviews with “dozens of persons”, but none were in Al-Jinah at the time of the attack.[11] It found that the strike killed one civilian, possibly a child, but noted it was proportional to a valid military objective, as it claimed to have struck a building, which was adjacent to a prayer hall, where an Al-Qaida meeting was taking place at which “regional leaders” were present.

- The United States Central Command stated that F-15 aircraft had struck the building adjacent to the prayer hall with 10 bombs, that an MQ-9 drone had fired two missiles at targets who had emerged from the building, and that the weaponry chosen had been designed to avoid collateral damage. It added that the team had had information on the target three days prior to the attack but had not begun target planning until the day of the strike. It also acknowledged that the team had failed to identify the religious nature of the buildings, admitting that that had been a preventable error. Finally, it found irregularities in changeovers of teams on shift, which had “contributed to a lack of situational awareness, knowledge and understanding among the strike cell individuals”.[12]

- Investigations into events surrounding the air strikes were initially focused on establishing whether a lawful target existed. The Commission collected satellite imagery and photos taken of the site, which confirmed the assessment of the United States Central Command that the weaponry used was intended to avoid collateral damage. Based on bomb fragments found at the scene, the Commission determined that the affected structure had been hit by numerous aerial bombs. An assessment of fragments found at the site, photos, satellite imagery and witness testimony reveal that up to eight GBU-39s (guided bomb units) and other munition were used. While only GBU-39 fragments were found, based on crater depth it is likely that two 500-pound joint direct attack munitions, with delay fuses, were also used. Delay fusing is used to contain collateral effects, as the bomb would detonate underground, collapsing a structure while keeping blast and fragmentation localized.

- The GBU-39, used to target specific parts of a building, is a low-yield bomb with minimal blast and fragmentation. It was used to destroy the target with minimal collateral damage to the surrounding area, including the adjacent prayer hall. A follow-on strike using two Hellfire missiles killed individuals fleeing the mosque. Indeed, Hellfire missile fragments were found outside the site, and fragmentation patterns on the road are consistent with a Hellfire missile containing a fragmentation sleeve around the warhead.

- Omar Bin al-Khatab mosque is part of a larger religious complex, which includes a service building adjacent to a prayer hall used for religious gatherings. Interviewees described it as the largest mosque in Al-Jinah and surrounding villages, and well-known in the area. Witnesses further identified the service building as the one directly hit by the air strikes. Apart from meeting rooms, the service building contained a kitchen to prepare meals for worshippers, a dining area and bathrooms. Interviewees referred to the service building as part of the mosque, and indeed such buildings are essential to the functionality of mosques, which commonly serve as community education and social centres for worshippers.

- Most of the residents of Al-Jinah, relatives of victims and first responders interviewed by the Commission stated that on the evening in question, a religious gathering was being hosted in the mosque’s service building. This was a regular occurrence at the mosque attended by hundreds of congregants: every Thursday, worshippers gathered for sunset prayer, a religious lesson followed by nightly prayer, and a meal. The air strikes hit the service building at approximately 6.55 p.m., just as the religious lesson was concluding and the meal was being prepared. The nightly prayer was scheduled to begin 15 minutes later. Interviewees described how several air strikes hit the centre of the building, causing it to implode. With the exception of 2 survivors, all others, estimated to be at least 15, who were in the kitchen or bathrooms, were killed. As people attempted to flee through the western door, a drone fired two missiles, killing them in the streets.

- In this instance, the service building was part of the mosque complex and was being used for religious purposes. Mosques are protected objects under international humanitarian law. Protected objects may not be made the object of attack unless used for military purposes, which would be the case if an Al-Qaida meeting, with regional leaders present, was in fact taking place. The United States Central Command has not released any details proving this was the case. Further, information gathered by the Commission does not support the claim that any such meeting was being held at that time. Interviewees described the gathering as strictly religious, and explained that most attendees were Al-Jinah residents, and that many of them were internally displaced persons, with the exception of some residents from neighbouring towns, such as Atarib.

- Some interviewees, however, noted an Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham presence in the village, and it cannot be ruled out that some members of that group may have attended the gathering. In this regard, the Commission notes that even though bombs designed to inflict low collateral damage were used, the United States targeting team lacked an understanding of the actual target, including that it was part of a mosque where worshippers gathered to pray every Thursday. Moreover, although the targeting team had information on the target three days prior to the strike, it did not undertake additional verification of target activities in that period, which would be expected were it known to be a mosque. The Commission therefore concludes that United States forces failed to take all feasible precautions to avoid or minimize incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects, in violation of international humanitarian law.

- Medical facilities

- Since its inception, attacks against medical facilities and medical personnel have been a tragic hallmark of the Syrian conflict. In an attempt to protect health-care infrastructure, personnel and patients, many hospitals and clinics in areas under opposition control have relocated underground, operating from reinforced basements and, sometimes, from caves dug into mountains. “Cave hospitals” are typically located on the outskirts of Syrian towns, without any other buildings in their vicinity. While such measures are intended to afford additional protection, intentional attacks against underground and cave hospitals continue to transpire.

- Between March and April, when Syrian and Russian forces heightened their aerial campaign to gain control of Kafr Zeita, Murek and Al-Latamneh, the only remaining towns in northern Hamah controlled by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and armed groups, a surge of air strikes on medical facilities in northern Hamah and southern Idlib were carried out. These attacks took place shortly before and after Syrian forces used chemical weapons in the same area (see paras. 69-70 and 72-77 below), thus preventing victims of chemical attacks from obtaining essential medical treatment. In one of the attacks, pro-Government forces used chlorine, while in another they used cluster incendiary munitions. The Commission has previously reported on pro-Government forces using such weapons to attack both medical facilities and individuals providing medical care in eastern Aleppo city.[13]

- In the afternoon of 5 March, an air strike hit the Al-Sham underground hospital in Kafr Nabl, southern Idlib, destroying two floors and a generator and injuring one hospital worker. Interviewees recalled that the hospital had been rendered out of service as a result of an air strike on 25 February, noting that the number of civilian casualties would have otherwise been significantly higher. On 25 March, at approximately 1 p.m., a Syrian air force helicopter dropped a barrel bomb on Al-Latamneh hospital, killing three civilian men — a surgeon and two patients — and injuring a number of staff and patients. Photos of remnants provided to the Commission depict an improvised chlorine bomb. Eyewitnesses heard the bomb make only a slight noise before releasing a yellow/greenish smoke that smelled strongly of cleaning agents. The use of chlorine is further corroborated by symptoms reported: at least 32 persons were injured as a result of the attack, most of them suffering from irritated throats and eyes, difficulties breathing, vomiting and frothing of the mouth. One interviewee said that some of the injured were armed group fighters. In this regard, the Commission notes that the use of chemical weapons is prohibited in all circumstances, including when a military objective is present.

- On 2 April, the Maarat al-Numan national hospital was struck by at least three delayed-fuse aerial bombs (see annex II, para. 15). Two days later, an air strike hit the Al-Rahma medical point in Khan Shaykhun (see annex II, paras. 17-18). A clinic in Heish, southern Idlib, was hit by air strikes on 7 April, and one eyewitness recalled seeing an airplane drop a bomb that released numerous smaller units, several of which hit the clinic’s fuel generator and started a fire, forcing the clinic to relocate. Photos of remnants indicate that the clinic was hit with a ShOAB-0.5 cluster bomb and cluster incendiary bombs. On 22 April, at approximately 2 p.m., an air strike hit a cave hospital in Abdeen, southern Idlib, killing seven people, including a 6-month-old girl awaiting surgery. Her parents, a nurse and three patients were also killed. On 28 April, at around 4 p.m., an air strike hit a surgical and maternity hospital in Kafr Zeita, causing damage to the facility. The hospital was aerially attacked again at 2 a.m. on 29 April, directly affecting the emergency room and forcing the evacuation of all patients to the only remaining hospital in Kafr Zeita, located in a cave. Later that day, at around 2 p.m., a third air strike completely destroyed the facility, where, until then, over 100 babies had been delivered each month. Satellite imagery shows air strike damage to the hospital facility, likely from a 250-kilogram blast weapon, and indications of several near misses.

- The number and frequency of attacks against health-care facilities, particularly repeated bombardments of the same facilities and routine lack of warnings, clearly indicate that pro-Government forces continue to intentionally target such facilities as part of a warring strategy, amounting to the war crime of deliberately attacking protected objects.[14] Deliberate attacks against health-care workers further constitute the war crime of intentionally attacking medical personnel. The 25 March attack on Al-Latamneh hospital with chlorine further violates the Chemical Weapons Convention. The Commission reiterates that the use of chemical weapons is prohibited under customary international humanitarian law regardless of the presence of a valid military target, including when used against enemy fighters, as the effects of such weapons are indiscriminate by nature and designed to cause superfluous injury and unnecessary suffering.

- Use of chemical weapons

- Between March 2013 and March 2017, the Commission documented 25 incidents of chemical weapons use in the Syrian Arab Republic, of which 20 were perpetrated by government forces and used primarily against civilians.[15] During the reporting period, government forces further used chemical weapons against civilians in the town of Khan Shaykhun, in Al-Latamneh, located approximately 11 kilometres south of Khan Shaykhun, and in eastern Ghouta.

- While Khan Shaykhun and Al-Latamneh are controlled by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, Ahrar-al-Sham and various Free Syrian Army groups, eastern Ghouta is primarily controlled by Jaish al-Islam and Faylaq al-Rahman. At the time of the use of chemical weapons in Khan Shaykhun and Al-Latamneh, Syrian and Russian forces were conducting an aerial campaign against Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and armed groups in northern Hamah and southern Idlib.

- At around 6.30 a.m. on 30 March — five days after the chlorine attack on Al-Latamneh hospital by Syrian forces (see para. 64 above) — an unidentified warplane dropped two bombs in an agricultural field south of Al-Latamneh village. Interviewees recalled how the first bomb made almost no sound but released a “toxic material” absent any particular smell, while the second bomb caused a loud explosion. As a result of the former, at least 85 people suffered from respiratory difficulties, loss of consciousness, red eyes and impaired vision. Among the injured were 12 male farmers located 300 metres away from the impact point, 2 of them minors. Nine medical personnel who treated patients without protection also fell ill.

- While the Commission is unable to identify the exact agent to which the victims of the 30 March incident were exposed, interviewees described certain symptoms, including a very low pulse in one case, and contracted pupils, suffocation, nausea and spasms in another, that indicate poisoning by a phosphor-organic chemical, such as a pesticide or a nerve agent. The absence of a characteristic chlorine odour, coupled with secondary intoxications among medical personnel treating victims, supports the conclusion that a toxic chemical other than chlorine was employed. Given that Syrian and Russian forces were conducting an aerial campaign in the area, the absence of indications that Russian forces have ever used chemical weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic,[16] and the repeated use of chemical weapons by the Syrian air force, there are reasonable grounds to conclude that the Syrian air force used chemical weapons in Al-Latamneh on 30 March.

- As part of its offensive to fully besiege Barza, Tishreen and Qabun (see annex III, para. 3), three rockets were launched on the afternoon of 29 March from government forces positions into a residential area of central Qabun municipality, close to the Al-Hayat hospital, as well as into neighbouring Tishreen. One of the rockets released a white cloud in Qabun and witnesses recalled the spread of gas, which smelled strongly of domestic chlorine. Thirty-five persons were injured, including one woman and two children. Victims exhibited symptoms consistent with chlorine exposure, including respiratory difficulties, coughing and runny noses. The most serious cases were treated with hydrocortisone l and oxygen. On 7 April, shortly after midday, Al-Hayat hospital received two men suffering from milder manifestations of the same symptoms. In the first week of July, government forces used chlorine against Faylaq ar-Rahman fighters in Damascus on three occasions: on 1 July in Ayn Tarma, on 2 July in Zamalka and on 6 July in Jowbar. In total, 46 fighters suffered from red eyes, hypoxia, rhinorrhoea, spastic cough and bronchial secretions.

- The gravest allegation of the use of chemical weapons by Syrian forces during the reporting period was in Khan Shaykhun. In the early morning of 4 April, public reports emerged that air strikes had released sarin in the town. Dozens of civilians were reported killed and hundreds more injured. Russian and Syrian officials denied that Syrian forces had used chemical weapons, explaining that air strikes conducted by Syrian forces at 11.30 a.m. that day had struck a terrorist chemical weapons depot.

- To establish the facts surrounding these allegations, the Commission sent a note verbale on 7 April to the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations Office at Geneva and specialized institutions in Switzerland requesting information from the Government. At the time of writing, no response has been received. The Commission conducted 43 interviews with eyewitnesses, victims, first responders and medical workers. It also collected satellite imagery,[17] photographs of bomb remnants, early warning reports and videos of the area allegedly affected by the air strikes. The Commission also took into account the findings of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons report on the results of its fact-finding mission.[18] Below is a summary of the Commission’s findings, elaborated in full in annex II.

- Interviewees and early warning reports indicate that a Sukhoi 22 (Su-22) aircraft conducted four air strikes in Khan Shaykhun at around 6.45 a.m. Only Syrian forces operate such aircraft.[19] The Commission identified three conventional bombs, likely OFAB-100-120, and one chemical bomb. Eyewitnesses recalled that the latter bomb made less noise and produced less smoke than the others. Photographs of weapon remnants depict a chemical aerial bomb of a type manufactured in the former Soviet Union.

- The chemical bomb killed at least 83 persons, including 28 children and 23 women, and injured another 293 persons, including 103 children. On the basis of samples obtained during autopsies and from individuals undergoing treatment in a neighbouring country, those who undertook the fact-finding mission of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons concluded that the victims had been exposed to sarin or a sarin-like substance. The extensive information independently collected by the Commission on symptoms suffered by victims is consistent with sarin exposure.

- Interviewees denied the presence of a weapons depot near the impact point of the chemical bomb. The Commission notes that it is extremely unlikely that an air strike would release sarin potentially stored inside such a structure in amounts sufficient to explain the number of casualties recorded. First, if such a depot had been destroyed by an air strike, the explosion would have burnt off most of the agent inside the building or forced it into the rubble where it would have been absorbed, rather than released in significant amounts into the atmosphere. Second, the facility would still be heavily contaminated today, for which there is no evidence. Third, the scenario suggested by Russian and Syrian officials does not explain the timing of the appearance of victims — hours before the time Russian and Syrian officials gave for the strike.

- In view of the above, the Commission finds that there are reasonable grounds to believe that Syrian forces attacked Khan Shaykhun with a sarin bomb at approximately 6.45 a.m. on 4 April, constituting the war crimes of using chemical weapons and indiscriminate attacks in a civilian inhabited area. The use of sarin by Syrian forces also violates the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction and Security Council resolution 2118 (2013).

- The Commission is gravely concerned about the protection of civilians in Ar-Raqqah Governorate, owing to the ongoing offensive by the Syrian Democratic Forces and the international coalition to repel ISIL from Ar-Raqqah city. While numerous neighbourhoods have been rapidly overtaken, over 190,000 civilians have been displaced to areas under the control of Syrian Democratic Forces in the north of Ar-Raqqah Governorate, where they reside primarily in the Ain Issa and Mabrouka camps. The camps lack the resources and capacity necessary to adequately care for those persons. The lives of up to 60,000 other civilians inside Ar-Raqqah city remain at considerable risk under daily air strikes. Protection concerns faced during the conduct of interviews remain an issue.

- The Commission is currently undertaking investigations into several allegations of aerial attacks in Ar-Raqqah, including an air strike on Al-Mansoura village, at the time held by ISIL, which reportedly caused up to 200 civilian casualties. The Commission has gathered credible information that, on the night of 21 March, an air strike hit the Al-Badiya school in Al-Mansoura, which since 2012 had been used to house internally displaced persons. At the time of the strike, over 200 people, mostly displaced families from Palmyra, Homs, but also from Hamah and Aleppo, were living at the former school, which is located approximately 1.5 kilometres from the village. Some of the victims were recent arrivals, including from Maskanah, Aleppo, while other internally displaced persons had been living there for years. The strike was carried out at night when residents were asleep. Almost all of those inside the school at the time of the strike were killed, while some survivors, including women and children, sustained serious injuries. Information currently available indicates that at least two families of ISIL fighters had been living in the school previously, but left about one month before the strike.

- After its offensive to take Manbij, Aleppo, from ISIL, the Syrian Democratic Forces required significant reinforcements to set the stage to retake Ar-Raqqah city. The need for increased “manpower” resulted in a surge in forced conscription of thousands of civilians, predominantly men and boys, and was accompanied by arrests of those unwilling to be conscripted. Investigations are ongoing.

- Civilians throughout the country continue to comprise the overwhelming majority of casualties in the Syrian conflict, while children and internally displaced persons remain among the most vulnerable to violence. The de-escalation agreement reached in Astana in May led to a discernible reduction in hostilities and, in turn, a reduction in civilian casualties, first in Idlib and western Aleppo, and more recently in the southern provinces of Dar’a, Qunaytirah and Suwayda’. While this reduction provides the basis for a broader ceasefire, implementation modalities must be promptly agreed upon and effectively applied; as demonstrated by previous ceasefire arrangements, delay in implementation undermines the sustainability of any such agreement and further risks placing civilians back in harm’s way.

- Across the Syrian Arab Republic, warring parties continued to lay sieges and instrumentalize humanitarian aid to compel surrender. Local truces in Fu’ah and Kafraya, in Madaya and Zabadani, and in Barza, Qabun and Tishreen have incorporated evacuation agreements that have resulted in the forced displacement of civilians from these areas.

- Throughout the reporting period, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, ISIL and armed group fighters targeted religious minorities using car and suicide bombings, snipers and hostage-taking. In Al-Rashidin, a car bomb targeted internally displaced persons from the previously besieged Shia Muslim towns of Fu’ah and Kafraya, killing 96 persons, including 68 children. Following the attack, dozens of people went missing, with armed groups taking at least 17 civilians hostage.

- Government forces used illegal chemical weapons on at least four occasions. In the gravest incident, the Syrian air force used sarin in Khan Shaykhun, killing dozens of civilians, the majority of whom were women and children. As the result of an aerial campaign by pro-Government forces in the area surrounding Khan Shaykhun, many medical facilities were destroyed, which compounded the suffering of victims of the sarin attack. In Idlib, Hamah and eastern Ghouta, Syrian forces also used weaponized chlorine.

- In ISIL-held areas, civilians remain acutely vulnerable to violence. In Ar-Raqqah, the ongoing offensive by the Syrian Democratic Forces and the international coalition to repel ISIL has rapidly overtaken numerous neighbourhoods in Ar-Raqqah city. Air strikes have reportedly resulted in significant numbers of civilians killed and injured. The offensive has also displaced 190,000 persons, many of whom are now living in perilous conditions. Investigations are ongoing.

- Recommendations

- In addition to the recommendations made below, the Commission reiterates the recommendations made in its previous reports.

- The Commission recommends that all warring parties:

(a) Immediately lift all sieges and cease strategies aimed at compelling surrender that primarily affect civilians, including starvation and denial of access to humanitarian aid, food, water and medicine;

(b) Conduct evacuations from besieged areas in line with international humanitarian law and Security Council resolution 2328 (2016), which require that evacuations of civilians be voluntary and to final destinations of their choice, and protect all civilians evacuated, including by treating them with dignity and preventing fear of harm;

(c) Refrain from future evacuation agreements that result in the forced displacement of civilian populations for political gains;

(d) Ensure adequate protection for all internally displaced persons and safeguard the right to return for internally displaced persons and refugees, including by guaranteeing their safety and property rights;

(e) Refrain from attacking cultural and historic sites when not used for military purposes and proactively assist in the safeguarding of such sites;

(f) Effectively ban the recruitment of children and their use in hostilities, and guarantee effective protection of child rights, including access to education;

(g) Take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to the civilian population when undertaking operations in civilian-populated areas, in particular during the offensive in Ar-Raqqah city and ISIL-controlled areas;

(h) Undertake investigations into the conduct of their forces and make their findings public.

- The Commission recommends that the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic:

(a) Immediately cease using chemical weapons, including weaponized chlorine and sarin, which by design cause superfluous injury and unnecessary suffering;

(b) In accordance with its obligations under customary international humanitarian law and Security Council resolution 2286 (2016), cease attacks on medical facilities, personnel and transport;

(c) Ensure that existing and future legislation concerning legal and administrative matters for individual civilians, including in relation to property rights, complies with international human rights law, refugee law and international humanitarian law, and is equally accessible for all Syrians, with particular consideration for all internally displaced persons and refugees;

(d) Grant the Commission access to the country.

- The Commission recommends that anti-Government armed groups:

(a) Comply with customary international humanitarian law and cease intentional attacks against civilians, including members of religious minorities;

(b) Refrain from kidnappings and hostage-taking, and conduct akin to enforced disappearance;

(c) Take urgent measures to discipline or dismiss individuals under their command responsible for such acts.

- The Commission recommends that the international community:

(a) In compliance with their obligations to respect and ensure respect for the Geneva Conventions relating to the protection of victims of international armed conflicts, refrain from providing arms, funding or other forms of support to parties to the conflict when there is an expectation that such support may be used to perpetrate violations of international humanitarian law, and ratify treaties that promote respect for international humanitarian law and international human rights law when transferring arms, in particular the Arms Trade Treaty;

(b) Refrain from adopting or implementing any unilateral sanctions (unilateral coercive measures) that are unlawful and impede the full realization of human rights by the Syrian people, in compliance with General Assembly resolution 68/162 (2013), and ensure that any lawful sanctions are strictly tailored, with appropriate exemptions, to minimize their impact on humanitarian assistance;

(c) Encourage efforts to promote accountability, including by actively supporting the establishment of the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism to Assist in the Investigation and Prosecution of Persons Responsible for the Most Serious Crimes under International Law Committed in the Syrian Arab Republic since March 2011, in accordance with General Assembly resolution 71/248;

- The Commission recommends that the Human Rights Council support the recommendations made, including by transmitting the present report to the Secretary-General for the attention of the Security Council in order that appropriate action may be taken, and through a formal reporting process to the General Assembly and to the Security Council.

- The Commission recommends that the General Assembly support its recommendations and enable the Commission to offer regular briefings.

- The Commission recommends that the Security Council:

(a) Support its recommendations;

(b) Include regular briefings by the Commission as part of the formal agenda of the Security Council;

(c) Use its influence with all relevant actors and stakeholders to ensure a comprehensive and all-inclusive peace process that maintains due respect for human rights and international humanitarian law.

Map of the Syrian Arab Republic

Inquiry into allegations of chemical weapons used in Khan Shaykhun, Idlib, on 4 April 2017

- Initial reports and allegations

- On the morning of 4 April, public reports emerged that shortly after sunrise a series of airstrikes were launched on Khan Shaykhun, a town in southern Idlib which borders northern Hama. Khan Shaykhun is controlled by armed groups including Ahrar al-Sham and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), an umbrella coalition of extremist factions led by terrorist group Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (previously Jabhat al-Nusra). Throughout the day, news outlets and social media reported that dozens of civilians had died and hundreds of residents were suffering from symptoms consistent with exposure to sarin. The allegations would amount to the first sarin attack in the Syrian Arab Republic since 21 August 2013 when approximately 1,000 people were killed in Ghouta due to sarin exposure. Some hours later, between 11.30 and 1.30 p.m., the al-Rahma medical point and civil defence centre in Khan Shaykhun, which neighbour each other, were reportedly hit by airstrikes while treating patients of the alleged sarin attack. The al-Rahma medical point served as the main trauma facility in Khan Shaykhun.

- Statements by Russian and Syrian authorities

- During the course of the day on 4 April, Russian and Syrian authorities made public statements concerning the events in Khan Shaykhun. Both denied the involvement of Syrian forces in the alleged sarin attack suggesting instead that terrorist groups were responsible. The Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation released a statement saying that the Syrian air force had struck a terrorist depot in Khan Shaykhun between 11.30 a.m. and 12.30 p.m., and that the depot included workshops where chemical warfare munitions were produced.[20] The Syrian Army issued a statement denying it had used chemical agents in Khan Shaykhun and that responsibility for the attack lied with militants.[21]

- Syrian and Russian officials continued to make statements after 4 April. At a press conference on 6 April, the Syrian Minister of Foreign Affairs repeated the Russian Federation Ministry of Defence claim by saying that the Syrian “army attacked an arms depot belonging to Jabhat al-Nusra chemical weapons”. He denied that Government forces had used chemical weapons instead explaining that the first airstrike carried out by Syrian forces in Khan Shaykhun on 4 April was at 11.30 a.m.[22] Subsequently, during an interview on 13 April, President Bashar al-Assad denied that the Syrian army had used sarin and said that the allegations were fabricated, noting “the West, mainly the United States, is hand-in-glove with the terrorists. They fabricated the whole story in order to have a pretext for the attack [on the Shayrat airbase]”. He added that “[i]f they said that we launched the sarin attack from that airbase, what happened to the sarin when they attacked the depots?”[23], suggesting the Syrian army’s deployment concept for sarin relied on the storage of the agent itself.[24] Finally, President al-Assad took the position that Khan Shaykhun is not a strategic area and that the Government does not have army or battles there.[25] On 2 May, the Russian Federation Ministry of Defence said that Soviet ammunition KHAB-250 was never exported outside of the USSR and was never filled with sarin.[26]

- To establish the facts surrounding these allegations, the Commission sent a note verbale on 7 April to the Permanent Representative of Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations requesting information from the Government. At the time of writing, no response has been received. The Commission conducted 43 interviews with eyewitnesses, victims, first-responders, medical workers, and persons who visited the site after the attack. It also collected satellite imagery,[27] photographs of bomb remnants, early warning reports, videos of the area allegedly impacted by the airstrikes, and reviewed photographs and videos of victims depicting symptoms. The Commission took into account the findings of OPCW report on the results of its Fact-Finding Mission (OPCW FFM).[28] Taken as a whole, this body of information allowed the Commission to reach the narrative of events and findings below.

- Khan Shaykhun’s location

- Khan Shaykhun, a town controlled by armed groups and HTS, is located along the M5 highway. The M5, often described as the most important highway in Syria, connects the country’s major cities including Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo, all of which are currently controlled by Government forces. Owing to its location, warring parties have fought for control over Khan Shaykhun since the early days of the conflict.

- In March, the area was viewed as having increased strategic value as armed groups and HTS successfully attacked Government positions in Hama. Government forces reacted by carrying out a counter-offensive in southern Idlib, including in Khan Shaykhun, and the neighbouring towns of Kafr Zeita, Murek, and Al-Latamneh in northern Hama. If successful, this offensive would give Government forces control over the only pocket in northern Hama controlled by armed groups and HTS. Interviewees confirmed that in the days leading up to 4 April, numerous airstrikes impacted towns around the area of Khan Shaykhun. The Commission has also investigated and made findings on several incidents using airdropped munition which took place in the area in March and April, including through the use of chemical weapons in Al-Latamneh,[29] and attacks on hospitals in southern Idlib and northern Hama.[30] The latter severely impacted the level of medical care which victims of chemical attacks received.

- The events of 4 April

- On the morning of 4 April, the sky was clear. At 6.26 a.m., early warning observers[31] reported that two Sukhoi 22 (Su-22) aircraft had taken off from Shayrat airbase, at least one of which was heading in the direction of Khan Shaykhun. Shayrat is a military airbase in Homs located approximately 120 kilometres south of Khan Shaykhun, and has been used by the Syrian air force throughout the conflict to launch attacks on Homs and Hama. Since late 2015, it is also used as a base by Russian forces. The Commission notes that two individuals interviewed by the OPCW claimed that on the morning of 4 April the early warning system did not issue warnings until 11 to 11.30 a.m., and that no aircraft were observed until that time.[32] The Commission has not gathered any information to support this claim, but rather the opposite, as detailed below. Eyewitnesses explained seeing a plane over Khan Shaykhun at around 6.45 a.m., and numerous interviewees recalled hearing messages from the early warning system 20 minutes prior to the strikes. As further examined below (paras. 17-18), 11.30 a.m. was the time when the al-Rahma medical point in Khan Shaykhun was attacked by airstrikes including cluster incendiary munitions, though not chemical weapons.

- At around 6.45 a.m., interviewees recalled seeing an aircraft flying low over Khan Shaykhun, which is consistent with the airspeed of the aircraft and the distance that needed to be covered. In the span of a few minutes, the aircraft, identified by interviewees as a Su-22, made two passes over the town and dropped four bombs. The Su-22 is easy to recognise, and difficult to mistake for anything else. Recognition features include a single vertical stabilizer, swing-wings, and flat intake mounted in the nose.[33] Satellite imagery, photographs, and video footage corroborate witness accounts that air delivered munitions hit the impact points of the four bombs. As previously found by the Commission, only the Syrian air force uses Su-22s,[34] an aircraft which has no night-time capability. The Russian Federation and the international coalition do not operate this type of aircraft. It is therefore concluded that the Syrian air force carried out airstrikes on Khan Shaykhun at around 6.45 a.m. on 4 April.

- Three of the bombs created loud explosions, causing damage to buildings though apparently only one casualty. Based on crater analysis and satellite imagery, the Commission was able to identify three conventional bombs, likely OFAB-100-120, and the remaining a chemical bomb. The chemical bomb landed in the middle of a street in a northern neighbourhood of Khan Shaykhun, approximately 150 meters from al-Yousuf park, close to a bakery and a grain silo, which interviewees explained was not operational and unused for any purpose after having been hit by an airstrike in 2016. Eyewitnesses further recalled how this bomb made less noise and produced less smoke than the other three bombs, which is confirmed by video footage of the attack. Photographs of the impact site show a hole, too small to be considered a crater, and the remnants of what appears to have been a Soviet-era chemical bomb. The small hole is indicative of a weapon which used a contact fuze and small burster to deploy chemical agents, with the kinetic energy of the bomb’s body creating most of the hole. Two parts of the bomb were found at the site, a large piece of the weapon body marked in green for chemical payload and a filler cap for chemical weapons. Although the Commission is unable to determine the exact type of chemical bomb used, the parts are consistent with sarin bombs produced by the former Soviet Union in the 250kg-class of bombs, which would have approximately 40kg of sarin, depending on the munition used.

- The weather conditions at 6.45 a.m. of 4 April were ideal for delivering a chemical weapon. Data based on historical weather forecasts indicates that the wind speed was just over three kilometres per hour from the southeast, that there was no rain and practically no cloud cover, and that the temperature was around 13 degree Celsius.[35] The OPCW FFM, in the absence of actual weather data recorded for Khan Shaykhun and instead relying on actual weather data recorded at three other locations in the area, concluded that the wind speed was low with uncertain direction, most likely coming from somewhere between the south and east. All available data indicates stable atmospheric conditions without significant turbulence. Under such conditions, the agent cloud would have drifted slowly downhill following the terrain features at the location (roads and open spaces), in a southerly and westerly direction. This is consistent with the observed locational pattern of individuals becoming affected by the agent cloud.