Mona Haj Yehya – Nour Awais

In a small house on the outskirts of Jabal ar-Ruz, Abu Yazan sits beside his son, who has never attended school. The child was born in Turkey during the years of displacement and attended kindergarten there in Turkish, in a safe learning environment. The school was nearby, and the teachers inquired about absences and contacted the parents if the child was late or seemed tired.

But after the family returned to Syria and settled in Jabal ar-Ruz, Abu Yazan was confronted with a completely different reality. The school is far away, and the taxi driver who transports the children only cares about the number of passengers.

He says cautiously, “I can’t send him alone… the road is dangerous, and the taxi driver only cares about the money. The more passengers, the more profit, but safety? Nobody is responsible.” In Jabal ar-Ruz and Wadi al-Mashari, where haphazardly constructed houses cling to the hillsides, the journey to school is like climbing a real mountain, navigating narrow, mostly unpaved alleyways and roads. Cars, motorcycles, and the footsteps of children and their parents jostle for space in this arduous struggle to reach school or work safely.

Abu Yazan speaks of the lack of supervision, of children being dropped off in the middle of the road, and of cars speeding past without anyone noticing. “Once I saw a service taxi drop off my son, and seconds later a car sped by… the road is dangerous, and I can’t bear the thought of anything happening to my son,” he says.

He contrasts his experience in Turkey with what he sees today: “In Turkey, there’s a school in every village, and the teacher asks every student why they were absent, why they were upset, why they were sick. They contact the parents, they follow up. Here? Nobody asks.”

He decided to keep his son at home, either teaching him or hiring a private tutor. For him, education is important, but safety is more important: “If he doesn’t go to school, he’ll study here. The important thing is that he’s safe. Education is important, but my son is more important.”

In western Damascus, more than 200,000 people live in a massive informal settlement. Although the area did not suffer direct destruction during the war, there isn’t a single government school there. All the children commute daily to schools in Mashrou Dummar.

Numbers and Suffering:

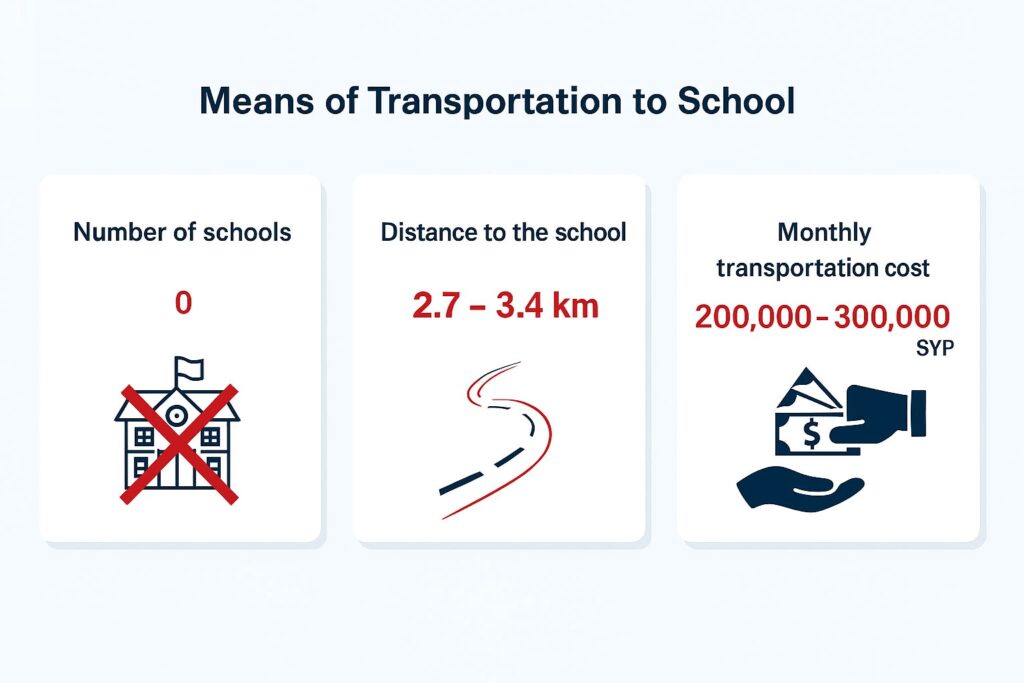

Residents of the neighborhood suffer from the lack of schools, forcing their children to endure a long and exhausting daily journey of up to 3.4 kilometers. The hardship is not limited to the distance alone; it also places a heavy financial burden on families, as transportation costs range between 200,000 and 300,000 Syrian pounds per child each month.

The Suffering of People with Disabilities

The situation is even more dire for children with disabilities whose dreams have been shattered and their right to education denied due to the lack of schools in the neighborhood.

Mohammed lives in a wheelchair, but he never stops dreaming. He was born thirteen years ago after his family was displaced from Aleppo. His ordeal began with his birth: a meningocele, multiple surgeries, a shunt implanted in his head, and a childhood that never knew its first steps.

His mother, wiping away tears, says, “For four years I’ve been trying to enroll him in school, but they wouldn’t accept him. They said the other children might hurt him, the suitable school was far away, and there was no transportation.”

Three years of knocking on the principal’s door, three years of rejection. In the fourth year, she was told her son was too old to be in a school with younger children. They promised her a vocational institute, but the journey there is longer than a mother burdened with children, debt, and a sick husband can bear.

Muhammad doesn’t study, he can’t walk, but he sees. He sees children going to school, returning with their bags, running through the streets, while he beats his legs a hundred times, crying out, “I wish I would die and be done with it.”

A Widespread Crisis

The investigative team met with five other families from the same area. What they all share is the hardship of the long distance to school, coupled with the deteriorating economic conditions of the residents and the fear that their children will drop out of school, if some haven’t already.

All the children of Jabal ar-Ruz and Wadi al-Mashari attend schools located in Mashrou Dummar. These schools often operate on a double-shift system (morning and afternoon) due to overcrowding. Although Jabal ar-Ruz was spared any destruction during the war and is considered one of the safest areas, the authorities have not allocated a single school there, citing the land as state property, the houses as informal settlements, and the lack of budgets.

A survey of more than 110 families from Jabal ar-Ruz and Wadi al-Mashari provided a more accurate picture of the reality of education in these marginalized areas. Responses were collected through paper forms and social media platforms, and the results confirmed the testimonies and revealed systematic patterns of marginalization. The results showed that the vast majority (94%) suffer from the distance of schools from their residential areas, and that some families spend around 400,000 Turkish Lira per month on transportation to schools.

The results also indicate that 23% of families have children who have dropped out of school due to poverty, disability, or the lack of integration programs for those returning from Turkey.

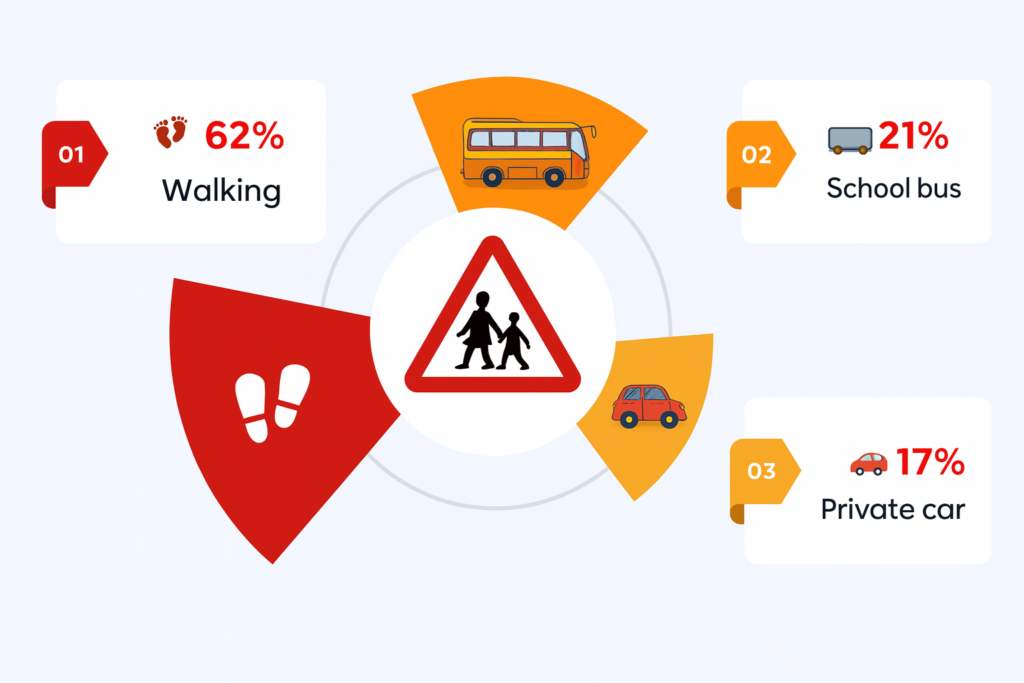

Means of Transportation to School:

Private Car/Taxi: 17%

Walking: 62%

Student Services: 21%

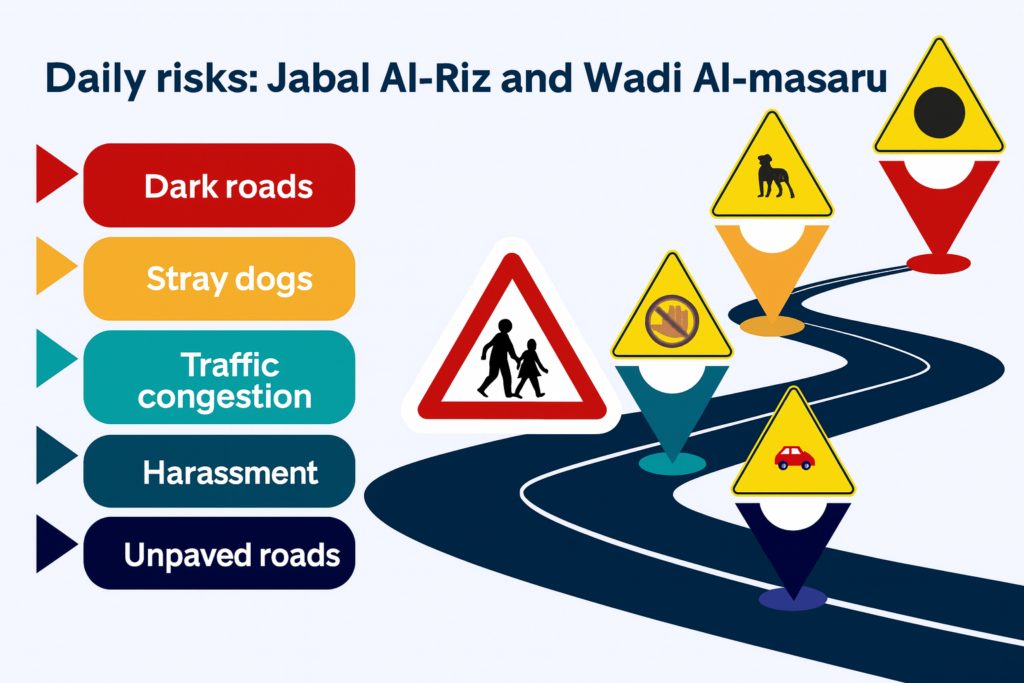

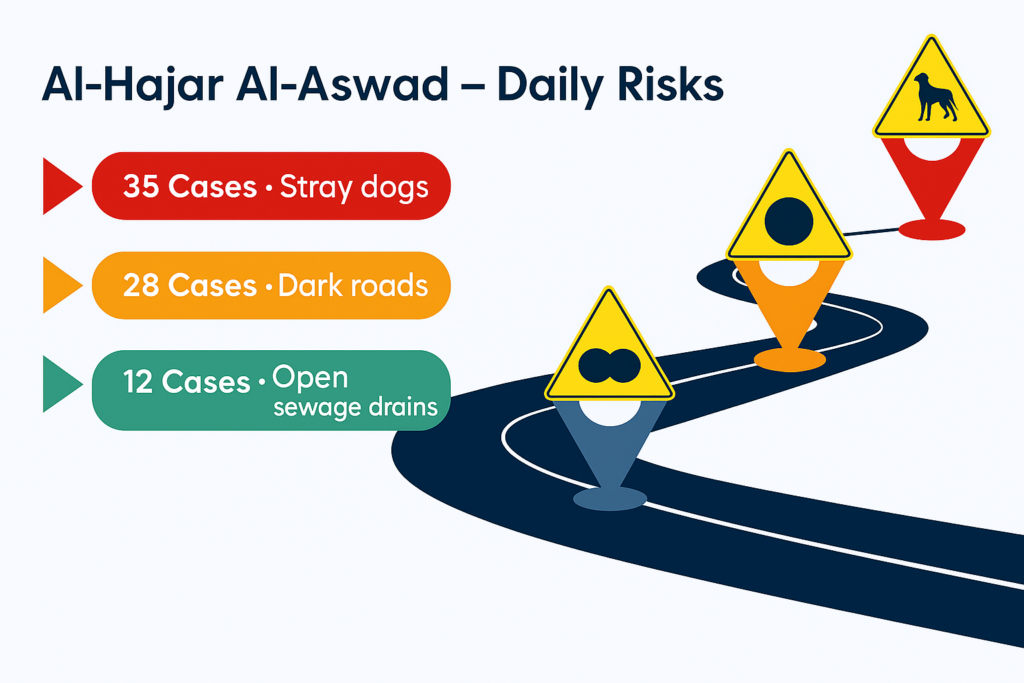

The students’ suffering does not end with the long distance; their daily journey turns into a path fraught with danger. They are forced to walk along unpaved roads, which further increase the hardship of commuting. With the onset of winter or delays in returning home, these streets are plunged into complete darkness, fueling fear—especially with the presence of stray dogs and the heightened risk of harassment. Upon reaching the main roads, they face another threat: heavy traffic congestion that endangers their physical safety.

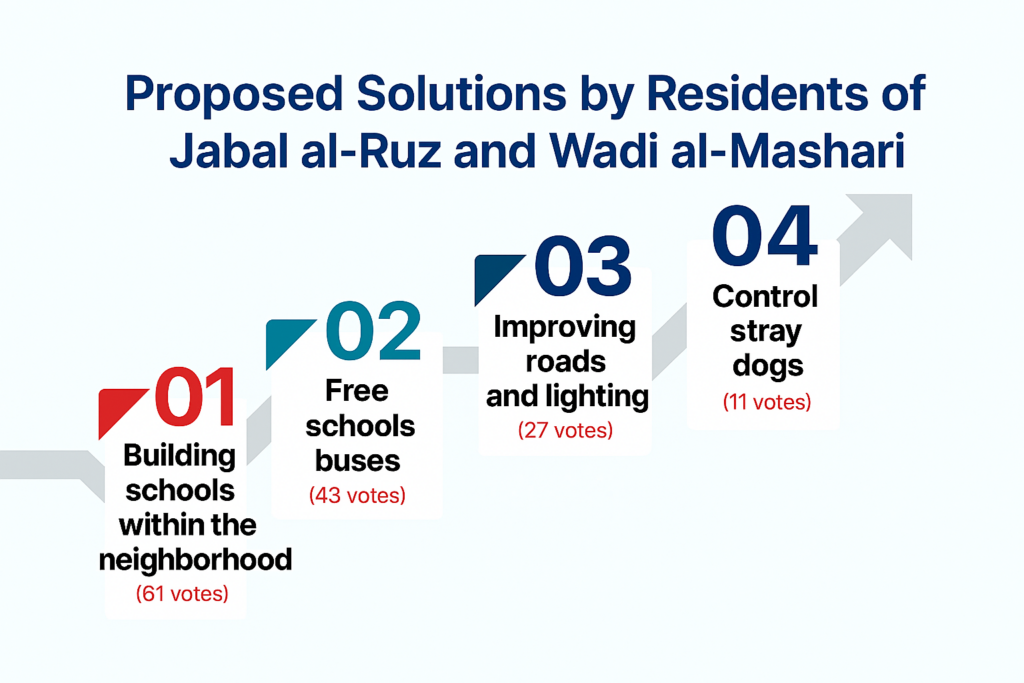

Proposed Solutions by Residents:

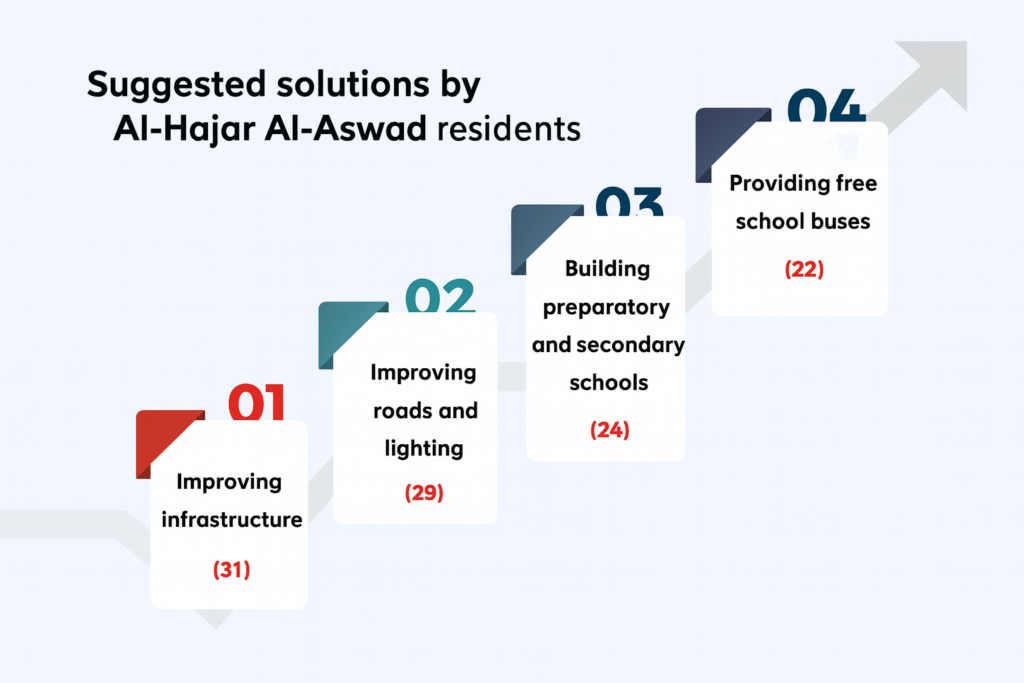

The residents’ proposals reflect a clear awareness of the root causes of the problem. The suggested solutions are divided into three main approaches: an infrastructural approach focused on building new schools; a service-based approach aimed at providing transportation and improving roads; and an organizational approach related to scheduling and integration. Below is a statistical overview illustrating the level of public support for each proposed solution:

Al-Hajar Al-Aswad: The Memory of War and Lost Dreams of Education

In a small, damp house in Al-Hajar Al-Aswad area south of Damascus, sits Bushra, a 43-year-old mother of four. She lost her husband at a military checkpoint twelve years ago, leaving her alone to face a harsh war and an even harsher life. “Since the day he left, I’ve become both mother and father,” she says in a low voice, gazing at a faded photograph of her missing husband. “There’s no one left to lean on, and everything falls on my shoulders.”

Her eldest son dropped out of school in the sixth grade to work in a plastics factory. “He works by the day, depending on the job,” she says. “Sometimes he earns fifty thousand, and sometimes he doesn’t earn anything. He works hard and endures, but he says, ‘The important thing is that we eat, Mama.'”

Her eldest daughter was married at the age of fourteen. “I married her off young, not because I liked it… but because I couldn’t provide for her expenses and needs. I felt that marriage would protect her, but every day I tell myself maybe I wronged her.”

Bushra recalls the moment she decided her son wouldn’t return to school: “I cried a lot. I felt like I was clipping his wings with my own hands. But I had no choice. I had to feed his siblings.” Despite everything she’s been through, a glimmer of hope remains in her voice: “My little girl dreams of completing her studies. I don’t want all my life’s hard work to go to waste. Maybe she can experience what we couldn’t.”

Bushra’s story is not an exception, but rather a reflection of the plight of dozens of women in Hajar al-Aswad who find themselves alone in the face of poverty, displacement, and the lack of education.

The two investigators interviewed four other parents from the same area, discovering how financial hardship prevented many of their children from continuing their education, and those fortunate enough to do so faced the arduous journey to school.

A City Without Schools

Before the war, al-Hajar al-Aswad was a vibrant, working-class neighborhood, but between 2015 and 2018, it endured a long siege and bombardment that destroyed approximately 80% of its infrastructure, including most of its schools.

After the previous regime regained control in 2018, some residents gradually returned, only to find that education had become an unattainable luxury. Only about 4,000 families have returned, out of a population of over 500,000 before 2011.

Most of the educational buildings in the neighborhood have been reduced to ruins. Only three schools are currently operating in the area—two affiliated with the Rural Damascus Education Directorate and one with the Quneitra Education Directorate. The distance to these three schools ranges between 2.7 and 3.4 kilometers in some neighborhoods, forcing some students to attend schools outside the area.

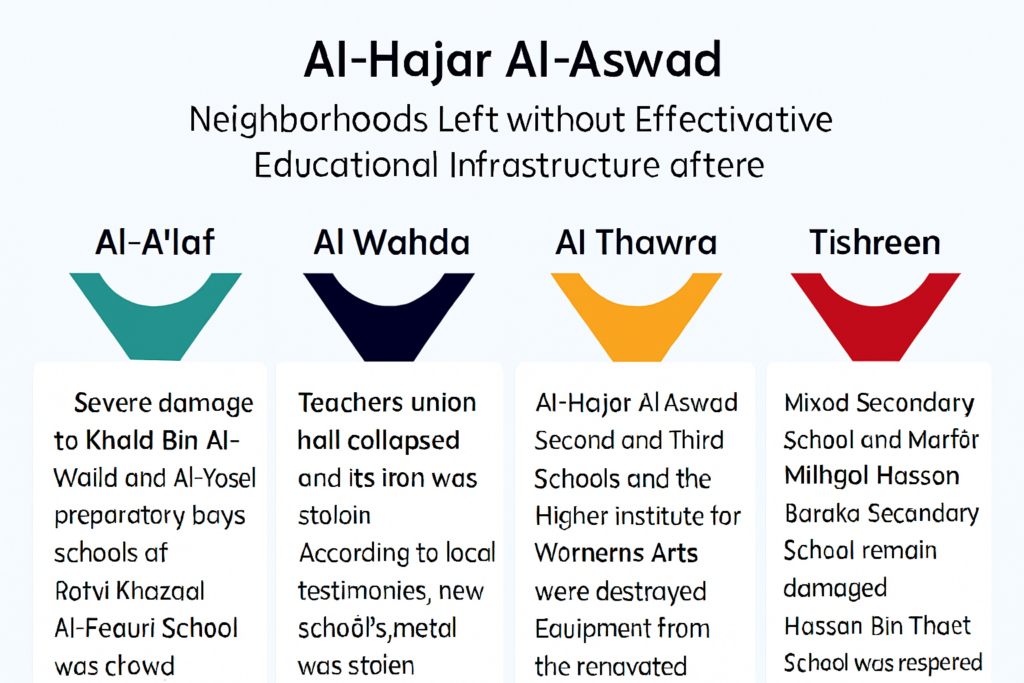

Infographic of Destroyed Schools

- Al-Thawra Neighborhood: The second and third Al-Hajar Al-Aswad schools and the Higher Institute of Women’s Arts were destroyed, while the equipment of the third co-educational school was stolen after its renovation.

- Tishreen Neighborhood: Schools such as the co-educational secondary school and the Martyr Mithqal Hassan Baraka secondary school remain damaged. The Hassan Ibn Thabit School has been reopened under the name Khalid Ibn Al-Walid.

- Al-Wahda Neighborhood: The Teachers’ Syndicate hall collapsed and its iron was stolen. Schools were destroyed in the earthquakes, and according to local testimonies, iron was stolen from the school.

- Al-Alaf neighborhood: Khalid bin Al-Walid and Al-Basil preparatory schools for boys sustained significant damage. Rahil Khazal Al-Faouri School has been closed.

The principal of Al-Hajar Al-Aswad Third School describes the educational situation within the school as “very poor and limited.” This is due to the school’s recent establishment, lack of basic facilities, and location in an area where the local community remains largely absent due to mass displacement and a lack of resources.

According to the principal, the school has 11 classes and approximately 200 students, from first to fourth grade. He noted that only eight students dropped out in the first semester. However, the school suffers from low attendance and poor discipline as a result of the remoteness of some neighborhoods and the difficult terrain.

Four Hours of Terror

In one of Al-Hajar Al-Aswad neighborhoods, a father recounts the story of four hours of terror he experienced after his two daughters got lost on their first day of school following the partial reopening of schools. “The school promised dismissal at 11:30, but they let the children out at 10:30 without informing us. The girls walked towards Yarmouk Camp and didn’t know the way.” The family spent four hours searching the streets, police stations, and mosques, which broadcast announcements over loudspeakers, until the two girls returned by chance on a bus. The father said, “We could have lost our daughters because of the school’s negligence. Education is important, but if we lose it, we lose an entire generation.”

This is not an isolated case; approximately 70% of children in the area walk to school, according to a survey distributed by the investigation’s authors, which included 33 families.

Due to the absence of secondary schools in the area, about 60% of those who responded to the survey said that their children spend between 30 and 60 minutes walking to school, enduring a difficult journey through dilapidated houses and unpaved roads.

Parents struggle with the high cost of transportation, which ranges between 100,000 and 300,000 Syrian pounds per month, threatening the ability of children from families living below the poverty line to continue their education.

Solutions suggested by the parents

The residents’ demands clearly demonstrated a preference for sustainable solutions, with infrastructure and educational facilities (including renovation and construction) topping the list of priorities by a significant margin. They also emphasized service and security aspects, highlighting the urgent need for safe transportation and student protection, along with other organizational proposals. The following table details the scope and distribution of these demands.

A Constitutional Right on Paper

Although the 2012 Constitution of the Syrian Arab Republic enshrines education as a right guaranteed by the state and emphasizes its free and compulsory nature until the end of basic education, the reality in areas such as Jabal ar-Ruz, Wadi al-Mashari, and al-Hajar al-Aswad reveals a deep gap between legal texts and actual practice. Article 29 clearly states that education is “a right guaranteed by the state and is free at all levels.”

However, in these neighborhoods, families pay between 200,000 and 400,000 Syrian pounds per month just to ensure their children’s access to schools located outside the neighborhood. This constitutional right has been transformed into a daily financial burden, forcing families to choose between food and education.

The reality in these neighborhoods also contradicts international standards. According to UNICEF, “education is a non-negotiable right, even in times of war and crisis.” Governments must provide a safe and child-friendly learning environment, guarantee children’s access to schools without financial or security barriers, provide support for children affected by war, poverty, or disability, and ensure safe transportation or reduce the distance between home and school.

Comparison Between the International Standards Approved by the World Bank and the Reality in Both Areas:

| International Standards | Jabal Ar-Ruz and Wadi Al-Mashari | Al-Hajar Al-Aswad |

| Neighborhood School | unavailable | Only 3 schools, serving other areas |

| Distance to School | 2.7–3.4 km | 2.7–3.4 km |

| Transportation | Walking (62%), unsafe public transport, expensive private cars | km walking distance, limited public transportation, damaged roads |

| Transportation Costs | 100,000–300,000 Syrian pounds per month, up to 400,000 | Up to 12,000 Syrian pounds per day per child |

| Safe Environment | Dark roads, stray dogs, harassment, traffic jams, unpaved roads | Rubbles, open sewage, risk of kidnapping and falls |

| Inclusion Programs | Absent, especially for those returning from Turkey | Unavailable, no psychosocial support |

| Support for Children with Disabilities | unavailable | unavailable |

| School Dropout Rate | 23% of children have dropped out of school | More than 40% of parents considered not enrolling |

| Community Involvement in Planning | Demands for school construction and safe transportation | Demands for school repairs and security measures |

| Population | Approximately 200,000 people | Only about 4,000 families have returned (official statement – 2025) |

UNICEF has confirmed that nearly fourteen years of conflict in Syria have left a profound impact on the lives of children and young people. More than 1.9 million internally displaced persons have returned to their communities, along with approximately 1.2 million refugees, more than half of whom are children, who have the right to a dignified and safe return to education and normal life.

UNICEF explained that high poverty rates and the distance to schools, especially in remote areas, are among the most prominent reasons hindering school attendance and increasing dropout rates. According to UNICEF, field evidence also shows that high transportation costs and long distances to schools place an additional burden on poor families, increasing the overall cost of education and negatively impacting children’s attendance. Some families have been forced to forgo basic necessities to ensure their children’s education.

As part of this investigation, urban planning and infrastructure expert Hisham Koussa was consulted to analyze the spatial factors that impede children’s access to schools in areas such as Jabal ar-Ruz and al-Hajar al-Aswad.

Koussa points out that the crisis of access to education in informal settlements stems not only from poverty or displacement but also from a lack of equitable urban planning, weak coordination among government agencies, and the marginalization of educational services in reconstruction policies.

He adds that the solution does not lie in building separate schools after the completion of neighborhoods but rather in integrating education into urban planning from its earliest stages, as a fundamental right around which the neighborhood should be built, not as a subsequent service added later.

The opinion also stressed the necessity for the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Public Works and Housing to include clear educational indicators within urban expansion maps, ensuring that schools and school transportation are included in public housing projects and organized informal settlements, rather than leaving them to chance or individual initiatives.

*This investigative report was prepared by the two journalists as part of a project implemented by the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), with support from NED.

The investigation was published on the Rozana website on February 20, 2026.