Haneen As-Sayed – Jihan Haj Bakri

In less than a week, more than 300,000 applications to import used cars were registered through a single government platform, immediately following the import ban issued in October 2025 by the Syrian Ministry of Economy and Foreign Trade.

These cars appear on the surface to be like any other means of transportation, but in reality, their engines bear a long history of wear and tear and a burden of emissions that exceed geographical boundaries and environmental regulations.

These are not just numbers; they represent massive shipments of dilapidated cars, damaged by flooding or reaching the end of their lifespan, forced upon the Syrian market as the final product of global automotive exhaust, in the absence of any environmental inspection or technical standards to ensure air safety.

Over the past few years, a massive wave of used and dilapidated cars has flooded into Syria, filling the streets and polluting the air. Between cheaply imported vehicles, highly polluting local diesel fuel, and unregulated, congested streets, Syrian cities breathe air thick with smoke.

Has Syria effectively become a global dumping ground for used cars rejected in Europe and the Gulf?

The full story

On the road between Aleppo and Idlib, as the investigation team was on its way to interview the driver “Abu Wissam,” thick smoke billowed from a vehicle ahead, filling the air with a suffocating weight.

Abu Wissam, a man in his forties, works delivering orders in his own car. While waiting for a new customer, he said, “I have no choice but to use a used car.” For him, used cars, despite their polluting emissions, are the only viable option after he sold a piece of his land to buy his car for $4,500. It’s a 2004 Korean-made model. He explains the reason: “The low prices, the availability of parts, and the ease of maintenance.”

Although his car’s engine releases thick clouds of black smoke with every start, some of which swirl around his head and obscure part of the sky above him, this doesn’t deter him from stopping. He smiles, turns the key again, and says, “It’s my livelihood. Without it, I can’t feed my children, and I’m not bothered to scrutinize the emissions.” Like many in Syria, Abu Wissam no longer has the luxury of considering alternatives. The sharp decline in purchasing power has made used cars almost the only option for citizens. But this “economic solution” masks a silent environmental crisis: a fleet of dilapidated vehicles pumps large quantities of pollutants into the air daily, in the absence of effective environmental policies and with little public awareness of the dangers of emissions.

Thus, economic necessity transforms into a continuous environmental burden, its scope expanding with every old car that takes to the road, and with every citizen forced to choose between a livelihood and clean air.

In another corner of the story stands Umm Fawaz, displaced from the town of Kafr Nabudah in the Hama countryside. She has lived for years in Sarmada, near the Bab al-Hawa border crossing, where cars enter the Syrian market daily. She says, “When I first moved to Sarmada, I started having asthma attacks and I was constantly using my inhaler. I didn’t know why until I noticed the smoke was everywhere.” In 2025, she returned to Kafr Nabudah, a partially destroyed but quieter and less crowded area. She says, “Within two months, I stopped using my inhaler. I could breathe… despite the destruction, I could breathe.”

In neighborhoods near busy streets, residents often complain of chronic coughs, shortness of breath, and respiratory infections.

While there are no reliable local health studies directly linking common respiratory symptoms in northern Syria to emissions from used cars, global scientific studies show a clear correlation between continuous exposure to fine particulate matter from vehicle exhaust and increased rates of asthma, cancer, heart disease, and chronic lung disease.

In this context, a recent research paper published on the arXiv platform refers to a concept known as “emission export” through the used car trade. The paper explains that countries importing these vehicles bear the greatest environmental burden, as they receive cars that are less fuel-efficient and emit more pollutants than if those cars had remained in their countries of origin.

How do these cars enter the country? And where do they come from?

The major wave of used car imports began after 2017, when customs restrictions were eased due to the multiplicity of governments and areas of control. This opened the door to what one of the traders interviewed by the investigation team described as a large margin for buying and selling in this trade, especially through the crossings in northwestern Syria.

With the decline in citizens’ purchasing power and the rise in new car prices, the used car became the only option for many, while the country gradually transformed into a preferred destination for traders of cars rejected abroad.

Official data and customs statements—according to the General Authority for Land and Sea Ports—indicate the registration of more than 212,000 used cars during the period when imports were permitted. This was before the government issued Decree No. 462 on June 29, 2025, which completely halted imports “due to the saturation of the local market,” with limited exceptions for trucks, agricultural machinery, and construction equipment.

However, this decree came too late; the country was already flooded with imports beyond its capacity. Despite this, cars continued to enter Syria nearly six months after the decree, under the pretext that some traders had already purchased their shipments and needed to bring them in.

According to the General Authority for Land and Sea Ports, 1,800 cars entered Syria after the fall of the regime via a ship arriving at the port of Tartus from South Korea on May 18, 2025, in the second such operation. A second ship carrying 3,181 cars entered via the Dolphin Shipping Company after the company resumed operations following a hiatus of more than ten years.

According to the plan announced on the General Authority’s Telegram channel, the company began operating three regular weekly trips between the Turkish port of Mersin and the port of Tartus.

According to media and economic reports, approximately 80% of the cars imported into Syria were used. Five traders we interviewed in northwestern Syria and the coast estimated that between 100,000 and 150,000 cars entered the region after the fall of the regime, with approximately 250-300 vehicles sold daily, mostly imported from Korea, the UAE, and the United States. New cars accounted for no more than 1% of these sales.

In a previous statement issued by the Salvation Government before the fall of the Assad regime, while it controlled only the Idlib region, it stated that the number of imported cars between 2022 and 2024 exceeded 106,500. However, we were unable to obtain any statements after the regime’s fall, except for information obtained from an official at the Bab al-Hawa border crossing. He stated that after the decision to ban the import of used cars was issued in October 2025, traders registered 300,000 cars through the designated registration platform within just one week of the decision’s implementation.

The routes these cars took to enter Syria were varied, some via Turkish border crossings, some through the Jordanian Free Zone, and others through the port of Tartus. A report published by The Jordan Times in early 2025 indicated that 3,664 cars had been exported from the Free Zone to Syria since the beginning of the year following the fall of the Assad regime.

Furthermore, recent official data from Jordanian Customs indicates that thousands of vehicles have been re-exported (in transit) to Syria since the reopening of the border crossings, reflecting an increase in the flow of cars. Although databases such as UN Comtrade and WITS confirm that Syria has been among the top importers of used cars in the Middle East in recent years, they also show that the majority of these cars come from Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, and the UAE, making these countries the main entry points for “European/used cars” into the Syrian market.

These figures reveal that Resolution 462 of 2025 was merely a belated response to a deteriorating environmental and economic reality. In less than a decade, Syria has transformed into a final market for the world’s used cars.

From Europe to the free zone in Jordan or Turkish ports, and from there to Syrian markets. While the new government speaks of “market saturation,” the deeper reality remains that used cars operate on the streets unchecked, meaning that halting imports will not stop pollution immediately, but will have a long-term impact on the air that Syrians breathe.

Ports Receive “What the World Has Discarded”

Customs broker Mohammad Mustafa Qasmo observes the influx of used cars at the port of Latakia, describing it as “the largest wave of imports the country has witnessed in years.” However, he believes this influx has been accompanied by a significant decline in the technical condition of the arriving vehicles. According to Qasmo, Syria has become a major dumping ground for cars imported from South Korea and the Gulf states, most of which are classified as “out of service” in their countries of origin. Despite this classification, they find their way into the local market due to the absence of environmental and technical regulations.

Qasmo points out that the impact of these vehicles extends beyond the technical aspects, affecting the infrastructure itself. Syrian streets are now crowded with cars over 15 years old, with low environmental ratings and high carbon dioxide emissions, while exporting countries are phasing them out to protect their domestic environments.

Al-Mukhlis suggests implementing a mandatory technical inspection in the country of origin before importing any vehicle, taking advantage of the advanced testing centers in those countries. He recalls that the Syrian government had reduced customs duties on imported used cars by 80% before recently banning them and allowing only new cars less than three years old from the date of manufacture. Qasmo believes this decision could gradually contribute to raising the level of technical safety and efficiency in the market.

The Syrian Car Market: Old Models

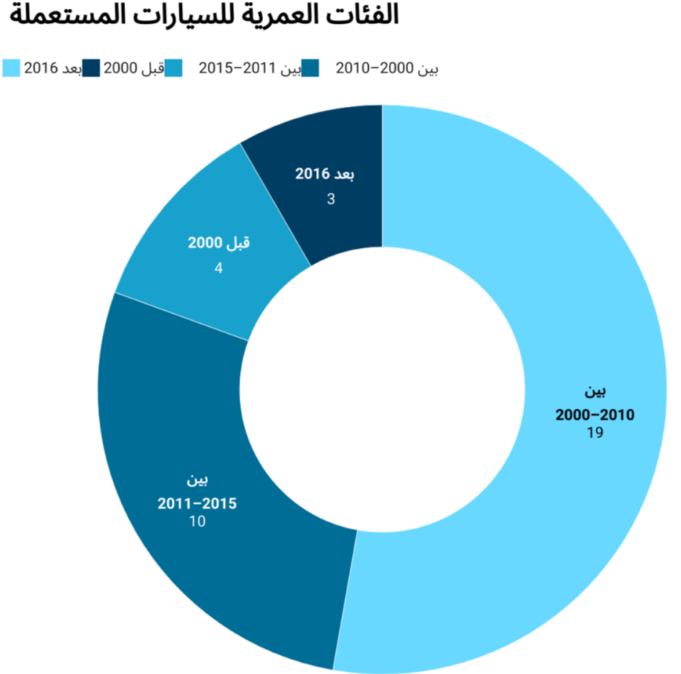

Before delving into the complexities of breakdowns and emissions, interviews with dealers and experts in northwestern Syria and the coast reveal a clear picture of what is happening in the used car market. The most prevalent models are those between 2007 and 2015, and this category forms the backbone of most daily sales. Because it’s the cheapest and most readily available on the market.

New cars make up no more than 4% of the total vehicles in northern Idlib, according to one dealer, making them a rare exception in streets overflowing with used cars.

According to the dealers we spoke with, the most sought-after segment is cars priced under $10,000, mostly models from 2010 and earlier. Customers prefer these due to their lower cost and ease of repair.

With the absence of environmental and technical oversight at entry points, according to the five dealers, these vehicles enter the market without proper inspection.

According to Abdul Latif Abu Amjad, a car repair shop manager with 13 years of experience, the cars they receive can be categorized into three main groups: those manufactured before 2008, which have worn engines and high emissions; cars manufactured between 2008 and 2018, which offer relatively better performance and are more technologically advanced; and cars manufactured after 2018, which are modern but negatively affected by the quality of locally available fuel. These figures paint a clear picture: a market flooded with used and imported cars, where the customer base relies on low prices above all else, and which continues to grow despite regulations and restrictions, driven by pressing economic needs and a weak regulatory framework.

The Environmental System… The Story of the Collapse of the Last Line of Defense in the Air

The problem of used cars in Syria is no longer limited to the age or origin of the vehicles, but has become embodied in the part that is deliberately removed before anything else: the environmental system, the system responsible for reducing toxic emissions. From repair shops to gas stations, and even customs ports, the same story is repeated: “The system is dismantled… because it is no longer useful, and in fact, it causes malfunctions.”

Vehicles that were originally withdrawn from international service because they no longer met Euro 5 and Euro 6 standards have entered the country. With the absence of emissions testing at the borders, Syria has become, as described by reports from Independent Arabia and Harmoon, “an open market for used European diesel cars.” While Syria’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) report submitted under the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC-NDC 2022) states that the transport sector is responsible for 24% of Syrian emissions, this figure does not take into account the recent surge in the number of cars, nor the near-universal removal of emissions control devices.

According to mechanic Abdul Latif Abu Amjad, based on his experience, 25% of cars arrive without emissions control devices at all, and another 25% have had them deliberately removed by their owners. Cleaning costs $35, a quick cleaning costs $8, and complete removal of the device costs between $100 and $300, leading many to view the device as a burden rather than a safeguard.

Abu Amjad asserts that the biggest culprit is fuel, saying, “Banias diesel has 90% more lead than Turkish diesel… This damages the sensors and the catalytic converter, and prevents the car from running properly.” According to the World Health Organization, there is no safe level of lead; its presence practically means toxic combustion that spreads into the air, soil, and water.

Software Disabling: Environmental Systems Disabled First via Computer

Mohammed Quban, a car repair shop owner in Idlib specializing in disabling environmental systems software via computer, says that removing the system begins on the computer before the unit itself is removed, because keeping the system active with this type of fuel damages the engine. He emphasizes, “The number of cars whose environmental systems we’ve disabled since 2022 is countless… the number is enormous and keeps increasing.”

This testimony aligns with what Mohammed Zeidan, who works at a car dealership in Sarmada, said: “Most customers ask about a place to dismantle the environmental system after purchasing a car because Banias diesel is unsuitable and causes endless problems.” The owner of the Al-Abdouli gas station in Azaz, north of Aleppo, explains that the diesel fuel arriving today comes from the Banias refinery and the rudimentary Tarhin refineries. He emphasizes the significant difference between it and Turkish diesel: Turkish diesel is clear and white, with a density of 815-825 kg/m³, meeting European EN590 standards, while Banias diesel is clear and yellow, with a density of 845 kg/m³, exceeding the European limit. This indicates the presence of heavy impurities or used oils. This density results in incomplete combustion, increasing soot and toxic gases, clogging filters, and damaging environmental systems.

On the other hand, Ibrahim Muslim, the director of the Banias refinery, states that the fuel conforms to national specifications, with a sulfur content of 0.35%. However, he notes that it is “unsuitable for modern, small diesel-powered cars,” which explains why many people have to dismantle their environmental control systems. Regarding lead, he asserts, “There is no excess lead… and the refining process is good.”

What do people say?

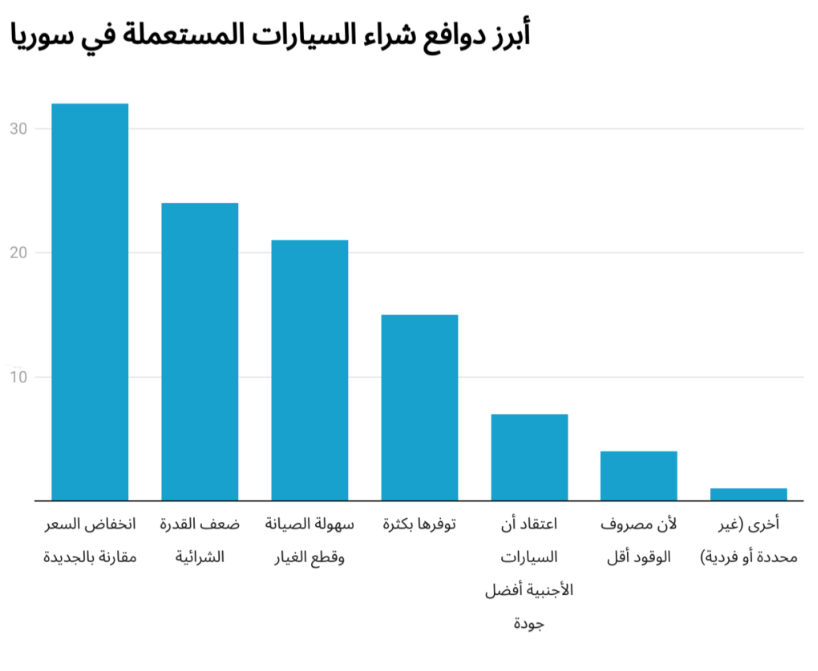

On this topic, we conducted a survey of over 40 participants from Idlib, rural Aleppo, and the Syrian coast, including drivers, car dealers, and ordinary citizens. The data revealed a complex landscape of economic motivations, a lack of awareness, and regulatory shortcomings in addressing the influx of old cars that are flooding the streets and exacerbating residents’ complaints about heavy emissions.

The vast majority of participants own used cars or rely on them as their primary means of transportation, reflecting the lack of economic alternatives, especially given the collapse in purchasing power. Despite this heavy reliance on vehicles, most participants asserted that they do not perceive any genuine concern within the community regarding environmental pollution. Responses ranged from “no” to “partially,” with only a few indicating limited awareness.

As for what needs to be done, suggestions varied but all converged on one goal: the necessity of imposing genuine oversight on cars before they enter the country. Some called for mandatory environmental testing of imported vehicles, others advocated for bimonthly inspections, and still others proposed imposing fines on cars emitting black smoke. It was clear that people directly linked the problem to the poor condition of vehicles and the lack of regulation. Calls also emerged for stricter import controls and a reduction in the entry of used cars, not only for environmental reasons but also to curb accidents caused by vehicles in poor condition.

These answers, though seemingly simple, paint a clear picture: residents of the north live in an environment saturated with old cars, feel the effects of pollution daily, and understand that the solution begins with inspecting cars before they enter the country, but they find no one to actually enforce it. Official Confrontation: Unanswered Questions

As part of this investigation, our team contacted the Syrian Ministry of Economy and Foreign Trade, submitting a series of written questions regarding the mechanisms for importing used cars, the adopted environmental inspection standards, the extent of compliance with decisions restricting the entry of older vehicles, and the measures taken to mitigate the damage to environmental systems and its impact on public health.

As of the time of publication, we have not received any official response from the Ministry to these questions, despite providing ample time for a reply. Any official clarification received will be published as soon as it is received, in accordance with journalistic ethics.

Key Drivers for Buying Used Cars in Syria

Reason for Purchase

Lower price compared to new cars

Weak purchasing power

Ease of maintenance and spare parts availability

High availability (wide supply)

Belief that foreign cars have better quality

Lower fuel consumption

Other (unspecified or individual reasons)

Age Categories of Used Cars

Between 2000–2010: 19

Between 2011–2015: 10

Before 2000: 4

After 2016: 3

Used European cars exported to Syria are classified internationally as “disguised mechanical waste.” They are either out of service or have been removed from European markets due to high emissions, yet they enter Syria without any inspection, relying solely on customs documents, according to the traders we interviewed.

From a broader perspective on the environmental situation in Syria, consulting engineer Rosa Jahmani, a specialist in climate policy and risk management, speaks of a complex reality that extends beyond the issue of used cars to the absence of a comprehensive environmental system. Rosa says that during her recent visit as part of her work with the Grains Green organization, she observed genuine local initiatives led by young people and associations, but these initiatives “operate independently,” without government oversight or institutional support.

Jahmani believes that environmental awareness rests on three pillars: understanding the problem, feeling the danger, and having an alternative. In Syria, these pillars are hampered by three main obstacles: the dire economic situation, which makes environmental concerns a “postponed luxury” compared to securing basic necessities; the lack of scientific knowledge and the absence of measurement and monitoring tools; there are no air quality monitoring stations, no environmental laboratories, and no devices for measuring PM2.5 particles, while international platforms rely on estimated models that do not accurately reflect reality.

She adds that sources of pollution are distributed throughout Syria and include old diesel vehicles, generators, unregulated waste burning, unfiltered furnaces and factories, and rudimentary refineries in the east. Despite this, Rosa sees genuinely positive signs in youth initiatives, a growing interest in health, and a community movement that has begun to link air quality to the rise in respiratory illnesses. However, she emphasizes that any change requires practical alternatives, such as improving fuel quality, regulating generators, curbing indiscriminate burning, and supporting the maintenance of older vehicles. These steps could make a noticeable difference even before a long-term national strategy is implemented. This investigation reveals what the statistics avoid saying: that the environment is not a luxury in a country suffering from this crisis, but a fundamental requirement for life. The path to cleaner air in Syria begins not only with bans but also with recognizing that the right to a healthy environment is a basic human right.

Unless this awareness translates into a clear national policy that prioritizes the environment over short-term considerations, the country will continue to buy cheap cars at a price that is irreplaceable.

This investigation was prepared by the journalists as part of a project implemented by the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, with support from NED. The content reflects solely the views of its author(s).

Notice:

This investigation is published with the permission of Haneen As-Sayed and Jihan Haj Bakri and constitutes an independent journalistic work produced by them. Its publication aims to make the content accessible to the public within the framework of interest in environmental and climate issues, without implying the adoption or endorsement by the Syrian Program for Climate Change or the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression of the views or conclusions contained herein. Copyright remains with the authors.

The investigation was published on the Syrian Program for Climate Change (SPCC) website on 13 December 2025.

The investigation was published on the SPCC website on 13 December 2025.

Official Response After Publication

Days after the publication of this investigation, the team received a written response from the Syrian Ministry of Transport, confirming that sustainable transport is a priority and that work is underway to establish a Supreme Council and a National Center for Sustainable Transport, in addition to implementing emissions testing within available resources.

The Ministry pointed to challenges hindering the effectiveness of environmental enforcement, including fuel quality, the age of the vehicle fleet, and the widespread practice of disabling emissions control systems.

However, the response did not include any data on the number of used cars entering the country, nor any documented health indicators regarding the impact of emissions on the population and referred these matters to other relevant authorities.

The investigation team affirms its commitment to pursuing any further clarifications or official statements received in the future, in accordance with the right of reply and journalistic ethics.

This investigation was prepared by the two journalists as part of a project implemented by the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, with support from the NED organization, and expresses the opinion of its author only.