Misleading Content and Sectarian Hate Speech

A Network of Interconnected Channels Fuels the Conflict in As-Suwayda

“Druze military forces torture a captive from the Bedouin tribal forces with acid,” a caption accompanying a video that went viral across 22 Telegram channels during the violence in As-Suwayda in early July 2025. However, analysis of this video, which attracted thousands of views, revealed it to be misleading. At the same time, dozens of posts containing hate speech circulated on hashtags shared by “Druze” channels on Telegram during the same period.

This data-supported report documents the spread of misleading rhetoric, sectarian incitement, and violent content from accounts inside and outside Syria, some of which were automated, on Telegram during As-Suwayda events, in violation of the platform’s policies prohibiting calls for violence.

A well-organized campaign

The video, which its publishers claimed showed the torture of a captive, spread across 22 Telegram channels with a unified post and shared hashtags. Within a few hours, the video had garnered 22,691 views from a total audience of 101,478 subscribers.

An analysis of the 22 channels that promoted the misleading video reveals a network with unified objectives, distributing standardized text and identical hashtags to rapidly repost it across channels of varying sizes and reach. These range from large, widely accessible platforms like “Qatada Saiqa – Syria” (23,691 subscribers), “Sada Syria – Official” (14,263), and “Taif News” (12,016), to smaller channels like “Al-Mulakhkhas (News)” (128) and “Minbar Al-Haqiqa” (170). Chronologically, both old and new channels published the same content within a short period. Geographically, the analysis revealed that the targeting was concentrated in the Syria and its sensitive areas, such as As-Suwayda and Deir ez-Zor, reinforcing the targeted nature of the posts.

Despite varying viewership—one channel reaching 22,691 views—engagement remained low, with the focus on reaching the audience rather than engaging in discussion. Most importantly, there was a complete absence of verification policies and source attribution; a video from 2018 was presented as a “leak” dated 8 August 2025, an example of manufacturing an echo chamber effect to build false credibility through repetition.

According to an official assessment received by the investigation team from the fact-checking network TruePlatform, the accompanying language in the video, such as “As-Suwayda is a jungle ruled by militias” and “Druze militias led by Hikmat al-Hijri,” creates a generalization about a religious sect and amounts to incitement to hatred. The video itself lacks essential elements of verification, such as when and where it was filmed, the identities of those appearing, the circumstances of their detention, and whether the burning actually occurred. This makes it an example of misleading exaggeration that increases its potential to incite violence, especially within the context of escalating sectarian tensions since mid-July 2025.

The Beginning of the Wave

Since the outbreak of As-Suwayda events on 12 July 2025, social media has played a role in fueling the conflict by disseminating hate speech, incitement, and sometimes explicit calls for violence. Although this discourse spread across most platforms, including Facebook, X, TikTok, and others, it was Its widespread use on the Telegram platform played a significant role in fueling hate speech and inciting violence.

The events on the ground began with tensions between Druze armed groups and Bedouin tribal fighters between 11 and 12 July 2025, before escalating with the entry of Syrian government forces into As-Suwayda city on July 15, under the pretext of “restoring stability,” and the imposition of a curfew. During July 15 and 16, Amnesty International documented the extrajudicial killing of 46 Druze individuals (44 men and two women) by government and affiliated forces in various locations, including Tishreen Square, residential homes, a government school, the National Hospital, and a community center.

The investigation team tracked Telegram channels and some of their associated accounts that were active during the events in As-Suwayda. These channels contributed to the dissemination of news, some of which was misleading and some of which incited violence. The common thread among these posts was their classification as hate speech.

Initially, we analyzed the posts, observing patterns of posting and interaction within a group of channels. This allowed us to identify initial connections between them. We then turned to Telemetr.io, an analytical platform specializing in monitoring Telegram channel activity. Telemetr.io measures growth rates and subscriber counts, and tracks the most shared posts and their associated hashtags. The tool confirmed a clear correlation between these channels and helped us identify those that were interconnected and coordinated in their posting, as well as those that amplified the spread by resharing identical content. This enabled us to create an initial map of the flow of misinformation.

The team also analyzed and categorized the visual and textual content based on its degree of violence and gore, using the Hive Moderation tool, which employs artificial intelligence techniques for content analysis. This was done to verify the nature of the circulated clips and classify them according to the criteria for violent or hate-inciting speech.

The team presented a diverse and random sample of the posts collected during the monitoring process to a specialist for classification based on the analytical criteria adopted in this investigation, which are consistent with international standards for digital platforms.

The investigation team also worked to verify the misleading posts that were monitored during the follow-up period, in order to identify their sources and patterns of dissemination, and to measure their impact on the course of public discourse. During the monitoring process, 139 posts were documented across 59 Telegram channels. These channels were distributed between those loyal to the interim transitional government, which were predominantly politically biased, and others opposed to it but aligned with the Druze forces. Any media outlet with a biased, pro-sectarian character—whether they belong to the Druze community or are aligned with it as a minority, as seen in the three Kurdish channels observed to be biased toward it—is clearly evident in its discourse and content.

A Fabricated Narrative

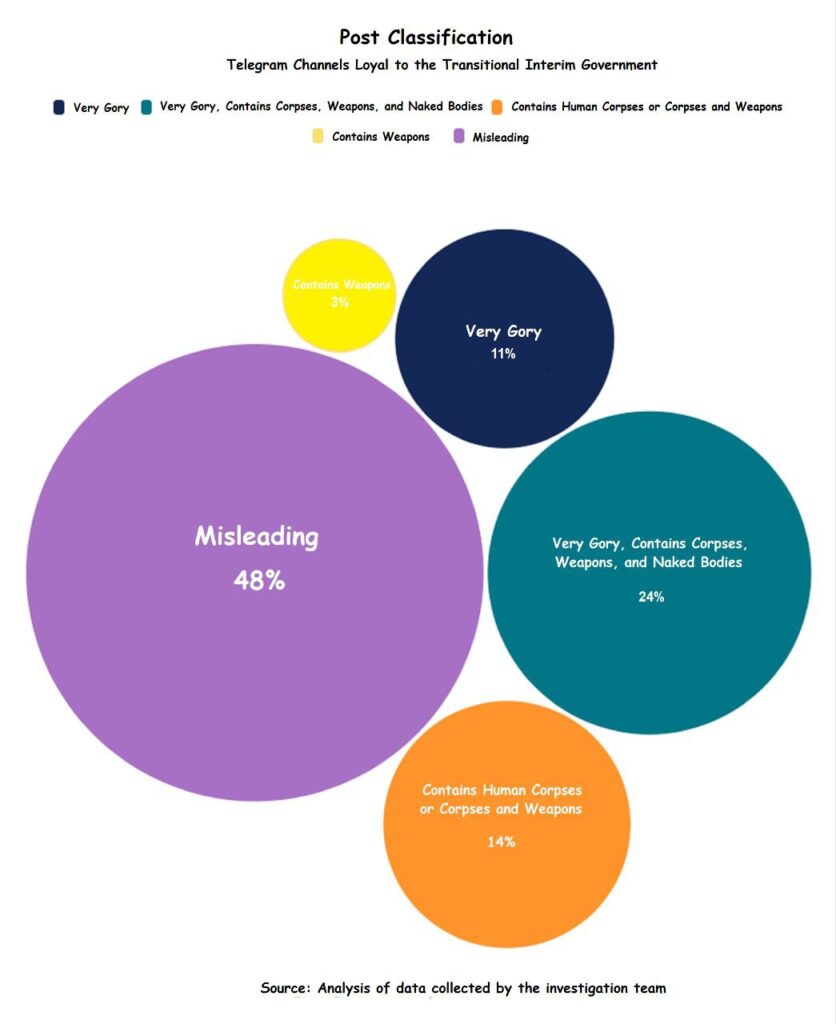

Through our investigation, we uncovered violent videos and images accompanied by claims that the perpetrators belong to certain Druze armed groups in As-Suwayda. These were accompanied by hashtags such as: #Al-Hijri’s_Dogs, #Documenting_Al-Hijri’s_Gangs’_Violations, #Al-Hijri_Traitor, or other hashtags that focus on condemning Al-Hijri, such as: #Justice_for_Victims, #Al-Hijri_Kills_Detainees, #Hikmat_Al-Hijri’s_Crimes, #Al-Hijri’s_Militias’_Violations. The common thread among these hashtags is the focus on Hikmat Al-Hijri, the spiritual leader of the Druze community, who led and directed military factions in battles against government forces and other armed groups, such as tribal forces. The promoters exploited Telegram’s lenient policies regarding the display of violent content. The investigation’s authors tested several models for reporting violent content, and the result was that these posts continued. Posts that were classified as bloody and contained images of corpses are still being displayed to this day without a single piece of content being deleted. Out of 61 posts, 24% were “very bloody and contained human corpses,” and 14% “contained corpses without blood.”

.”

We analyzed 61 posts across 35 channels with a total of 220,358 subscribers, garnering 82,762 views and 72 shares. The analysis revealed identical text, consistent hashtags, and recycled visuals presented as a new event each time.

Of the 61 posts, 29 were explicitly misleading, while 27 contained sensitive and violent content. Fifteen posts were categorized as “very gory,” containing human corpses. Eight posts contained human corpses without blood, and seven were highly gory, all of which were naturalistic, some featuring naked people and men carrying weapons, according to Hive Moderation’s analysis.

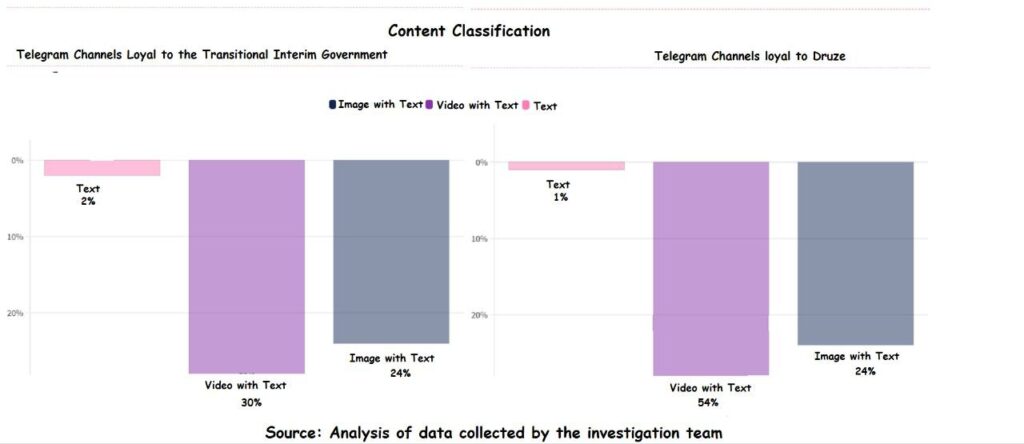

The posts followed a relatively consistent format: 20 posts were image with text, 33 were video with text, one combined image and video, and six were text only. The timing of the channels’ publications reveals the relationship between the events and the content: 14 channels were created in 2025; four of them in July, coinciding with the events in As-Suwayda; eight in 2024; three in November, coinciding with the “Deterring Aggression” military operation that led to the fall of the former Syrian regime in late 2024; seven in 2023; and two in 2022. The “Deterring Aggression” military operation was a large-scale escalation launched by opposition factions in northwestern Syria in late 2024 against regime forces and their allies, making it a pivotal event whose repercussions were directly reflected in the activity of the online channels covering those events.

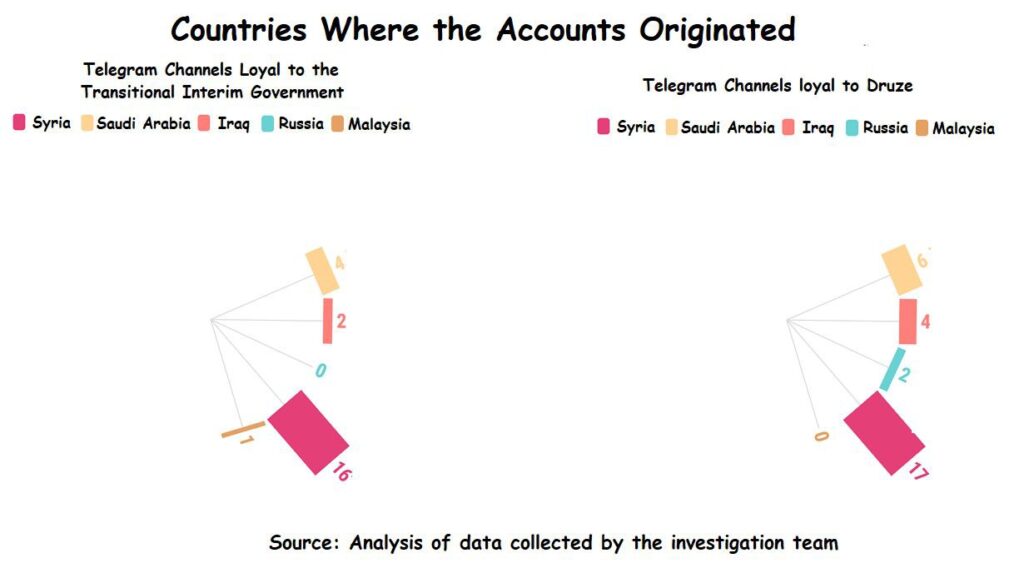

Based on Telemetr data, the geographical reach of the campaign becomes clear: 22 channels broadcast from Syria and four from Saudi Arabia, while the location of nine channels was not specified. Analysis of 26 channels linked to this network revealed a subscriber base of approximately 401,876. Among them are 16 channels from Syria, four from Saudi Arabia, two from Iraq, one from Malaysia, and three whose locations are unknown.

The creation dates are distributed across the peaks of events: six channels were established in 2025, six in 2024 (two coinciding with the “deterrence of aggression” operation), six in 2023, in addition to two in 2019 and two in 2018. This suggests that the number of channels expands with each new phase of the conflict.

At the heart of this network stand channels linked to journalist Muhammad Jamal, who presents himself as a “war correspondent in the Syrian Ministry of Defense.” His channel has been broadcasting from Syria since April 2023 with 98,792 subscribers. It features a uniform visual presence (military uniforms, Syrian flags, and the “eagle” logo) and similar names, all bearing the suffix “Syria” indicating a coordinated system rather than isolated individual accounts.

Alongside this, there are channels belonging to individuals with ambiguous identities, such as “Obaida Al-Furati Syria” which has 2,767 subscribers. This channel shared the misleading “prisoner video” before being deleted. With conflicting profiles, we found the channel archived on Telemeter and an image of an account belonging to a person killed in early December 2024 during a counter-offensive operation, named Abu Abdul Rahman.

Similarly, there is the channel “Free Journalist Abu Al-Shaymaa Al-Janoubi,” which publishes similar content without any possibility of verifying its owner’s identity. In contrast, the channel “Akram Hijazi – The Observer for Studies and Research” represents a well-known public figure with a research and media presence on YouTube and X. His Telegram channel, based in Syria since 2017, has 7,673 subscribers. However, it also shared the misleading “prisoner video” and an old video of a doctor from As-Suwayda, which was republished out of context and presented as related to current events.

We also observed the publication of another misleading video, which it claimed featured a Druze doctor “breaking her silence and revealing the extent of violations against doctors in As-Suwayda following attacks by the Military Council.” Upon investigation, the video was found to be old, having been published last May on Suwayda24 network and unrelated to current events or the present context.

To test the actual impact of the language used in this campaign on shaping public opinion, the investigation team submitted eight examples of these posts to the fact-checking network TruePlatform, requesting a formal assessment of the nature of the discourse employed.

The assessment revealed that six of them contain explicit hate speech that not only describes alleged violations attributed to armed groups, but also systematically generalizes the accusation to “Druze militias,” “Hijri gangs,” and the residents of As-Suwayda as a single entity, through language that dehumanizes them, collectively links them to crime, and uses degrading moral descriptions and animalistic metaphors, thus placing them in the category of hate speech, according to the content classification standards adopted by “True Platform”.

This impression is reinforced by posts that directly defame individuals by publishing their names and phone numbers, or include explicitly threatening language, thus raising the level of incitement and, in some cases, transforming it into an implicit or explicit call for violence, especially in a context charged with sectarian violence since mid-July 2025.

The network classified one example as misleading content that recycled an old video of summary executions in the context of the recent escalation without explicit hate speech, while another example emerged as hostile rhetoric specifically targeting the “Hijri militias,” with a clear potential to be transformed into incitement within the prevailing climate of sectarian polarization.

Accordingly, True Platform’s assessment concludes that these posts—with their texts and visual templates—represent a qualitative extension of the quantitative analysis’s hashtag patterns centered on Hikmat al-Hijri and the Druze community. They function more as politically motivated violent content and hate speech directed against an entire religious group than as accurate documentation of violations amenable to independent verification.

The Counter-Wave

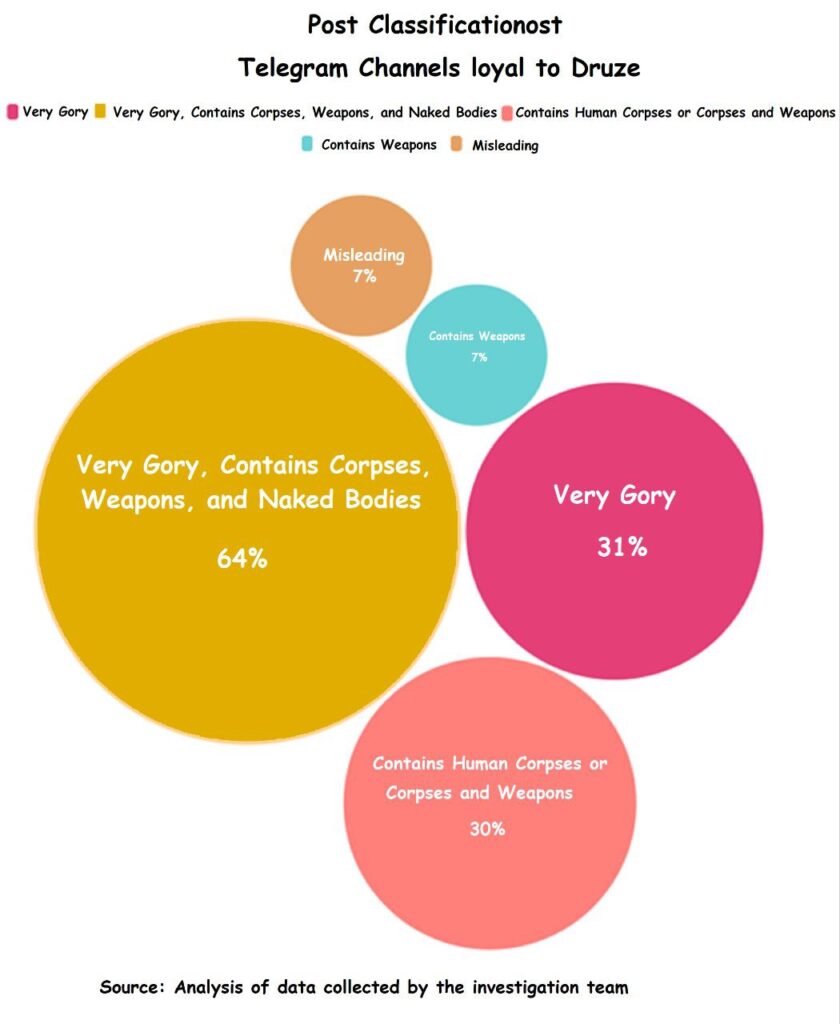

At the same time, what initially appeared to be a wave of “sympathy” for the Druze turned out, upon tracking and analysis, to be a disciplined network. During the monitoring process, we analyzed 74 posts from 30 interconnected channels in various ways: repetition of the same image and video, recycling of text, and standardization of hashtags such as: #As-Suwayda_Fights_Terrorism, #As-Suwayda_Under_Siege, #Save_As-Suwayda, and #Druze_Resistance. Tracking the relationships using Telemetr revealed that the channels clustered into clear groups, with overlapping sources of material, writing styles, and posting timing, suggesting a coordinated campaign rather than spontaneous expressions of sympathy.

In terms of visual content, Hive Moderation’s analysis confirmed that all channels published shocking material: gory images, human corpses, weapons, and naked people—all “natural” and unmanufactured material. The content was repetitive across the network: 21 posts with images and text, one post with only images, six videos without text, and 46 videos with text that presented the violent scene prominently, leaving the text to reinforce hashtags and accusations.

While the level of disinformation was lower than on pro-government channels—five misleading posts were recorded—hate speech was high, with 12 posts containing insults and derogatory terms such as “pigs,” “dead animals,” “extremist groups,” and “al-Julani’s gangs.”

The publishing network itself is divided into two prominent blocs. The first group exhibits high coordination in timing and content, with recycled texts, images, videos, and hashtags. Channels bearing the symbol “313” (a reference point for the Shia community) are prominent within this group. The sources of these channels are geographically diverse, spanning Syria, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq, and their names do not exclusively refer to As-Suwayda but rather cover a wider Syrian landscape.

The second group is attributed to the political and media activist Shadi Abu Ammar, a As-Suwayda-born refugee residing in the Netherlands. He emerged in 2022 as a prominent voice opposing the former Syrian regime, and his Telegram channel boasts over 35,000 followers with thousands of views per post. This group displays less intense coordination, but features standardized hashtags and content sharing within the group. It also originated in Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, with most being established after the fall of the previous regime in December 2024. Its members bear names that explicitly identify them as being from As-Suwayda. Examples include “Druze Resistance,” “Mountain News,” and “Voice of As-Suwayda,” along with a channel by Shadi Abu Ammar broadcasting from Iraq.

The 30 channels have a total of approximately 277,543 subscribers; their 74 posts garnered around 263,726 views and 912 shares. Geographically, 17 channels are attributed to Syria, five to Saudi Arabia, four to Iraq, and six are unidentified.

Chronologically, 22 of the 30 channels were launched after the fall of the regime, and eight were launched after 25 April 2015, a period marked by escalating violence against the Druze in As-Suwayda and Damascus suburbs. Four channels were created during the latest escalation, three have no date available, one dates back to 2022, two to 15 February 2024, one to 4 August 2024, and another to 2023.

According to Hive Moderation, 29 posts were classified as “very graphic,” with most images and videos depicting corpses, naked men, and weapons. One violent post identified a child.

Based on this context, the fact-checking network TruePlatform linked the quantitative data revealed by its monitoring tools (an interconnected network of channels, violent visual content, and uniform hashtags centered on As-Suwayda and the Druze) to the nature of the accompanying discourse. The assessment of 11 posts revealed that three of them simply described what were presented as “massacres” against civilian families or questioned the involvement of children in the fighting, without resorting to sectarian insults or generalizations about any specific group. Conversely, seven examples contain derogatory and dehumanizing language and glorification of violence, ranging from the use of terms like “dead animals” and “pigs” to describe opponents and residents of other areas, to explicit statements such as “When I say burn and grind, believe me,” or the cursing of an entire religious sect. Furthermore, various opponents are linked to “al-Qaeda” or “al-Julani’s gangs” in a context that does not always provide clear evidence and lends a celebratory air to their elimination. The final example is a silent clip showing a fighter, believed to be Druze, slapping a bound prisoner. While the accompanying text does not contain hate speech, its inclusion within the context of a sectarian conflict makes it part of a narrative that normalizes humiliation and violence, rather than a neutral documentation.

Monitoring and Reporting

At the height of the tension surrounding the recent events in As-Suwayda, “Report” initiative emerged as a practical mechanism for monitoring hate speech in its initial stages. Mohammad Al-Jasim, coordinator of the initiative to combat hate speech and violence, explains that the platform operates on two parallel tracks: the first is an open link that allows any user to provide the team with specific content for reassessment before being forwarded to the relevant authorities in the country concerned; the second is a guide within the platform that provides legal reporting maps for each country, ensuring that the reporter is not lost amidst varying legislation and complex procedures.

The initiative has received approximately 250 reports so far, about 40% of which were disqualified due to invalid links or insufficient information. The classified samples revealed nearly 30 cases of direct incitement to violence and approximately 35 cases of explicit hate speech, with the remainder ranging from less explicit insinuations to more subtle forms of hate speech.

According to the initiative’s coordinator, most reports originate from Facebook, followed by Telegram and then X, while the same discourse is disseminated across multiple platforms and from the same accounts. The danger is amplified within closed WhatsApp and Telegram groups, including systematic cases targeting Druze students at the Faculty of Medicine at Damascus University. This occurs amidst technical challenges such as the duplication of content and the impossibility of rapid closure, and legal challenges stemming from the requirement of shared jurisdiction. Upon receipt, the material is evaluated, identities are verified, and available measures are taken.

To counter the rise of hate speech in Syria, the initiative is working on three fronts: first, developing legal avenues and alliances; second, building a Syrian “hate dictionary” to train a linguistic model that identifies hate speech through its dialects and symbols; and third, an awareness campaign titled “Bread and Salt” that intersects with narratives through traditional figures and dramatic scenes. Periodic reports are prepared summarizing the patterns of reports and their outcomes, while the reporting mechanism remains open under professional oversight to ensure accuracy and procedural integrity, according to the initiative’s founder.

Digital Censorship Gaps

The investigation team conducted a comprehensive review of content publishing policies across three digital platforms; These platforms are Meta, X, and Telegram. Comparisons show that Telegram has a lenient or even tolerant policy towards violent or hateful content. For most harmful types, it relies on post-reporting rather than proactive monitoring and lacks an effective anti-misinformation mechanism, which prolongs the lifespan of hostile content and allows it to spread. While it strictly prohibits child sexual exploitation content, this exception does not alter its overall pattern of leniency towards hate, violence, and misinformation.

Meta, for example, has shifted since the beginning of 2025 to less stringent standards, allowing more space for offensive expressions under the guise of “public discourse.” It has also reduced its reliance on external verification in favor of contextual mechanisms similar to “community feedback.” Furthermore, its algorithm has faced recurring criticism for favoring sensational content, including incitement and misinformation, because it encourages engagement.

Although X has written policies against targeting based on protected attributes and uses Community Notes as a collective tool to combat disinformation, policy enforcement has become more inconsistent since 2022. Studies, such as one by experts from the University of California, have observed a significant rise in hate speech following the platform’s ownership change.

Data analysis reveals that what accompanied the events in As-Suwayda was not merely a passing linguistic outburst, but rather a system of channels that recycles graphic content and standardized hashtags, thereby reinforcing persistent sectarian narratives. This pattern of repetitive content production goes beyond documenting violations or reporting news; it aims to construct a specific narrative of the conflict.

At the same time, the platforms’ reporting and oversight gaps demonstrate the inadequacy of current frameworks to address this coordinated content, leaving the burden to limited civil initiatives and fact-checking efforts. The investigation concludes that curbing hate speech in a fragile context like the current Syrian context is not limited to developing platform tools, but also requires clearer local legal frameworks, and systematic coordination between the judiciary, regulatory bodies, and specialized initiatives.

*This investigation was prepared by a team of journalists as part of a project implemented by Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, with support from the NED, and published in cooperation with Suwar Magazine.

investigation was published on Suwar Magazine on 02 January 2026