Murky Money Trail, Missed Targets, Missing Data

(Beirut) – Millions of dollars in aid money pledged to get Syrian refugee children in school last year did not reach them, arrived late, or could not be traced due to poor reporting practices, Human Rights Watch said today.

The 55-page report, “Following the Money: Lack of Transparency in Donor Funding for Syrian Refugee Education,” tracks pledges made at a conference in London in February 2016. Human Rights Watch followed the money trail from the largest donors to education in Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan, the three countries with the largest number of Syrian refugees, but found large discrepancies between the funds that the various parties said were given and the reported amounts that reached their intended targets in 2016. The lack of timely, transparent funding contributed to the fact that more than 530,000 Syrian schoolchildren in those three countries were still out of school at the end of the 2016-2017 school year.

“Donors and host countries have promised that Syrian children will not become a lost generation, but this is exactly what is happening,” said Simon Rau, Mercator fellow at Human Rights Watch. “More transparency in funding would help reveal the needs that aren’t being met so they could be addressed and get children into school.”

Donors and the refugee-hosting countries that neighbor Syria agreed at the London conference to enroll all Syrian refugee children in “quality education” by the end of the 2016-2017 school year – and to provide the needed funds. According to the six donors that pledged the biggest sums – the European Union, the United States, Germany, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Norway – their contributions alone exceeded the overall 2016 target of US$1.4 billion for education inside Syria and for refugee-hosting countries in the region. Yet, education budgets in countries hosting refugees were substantially underfunded.

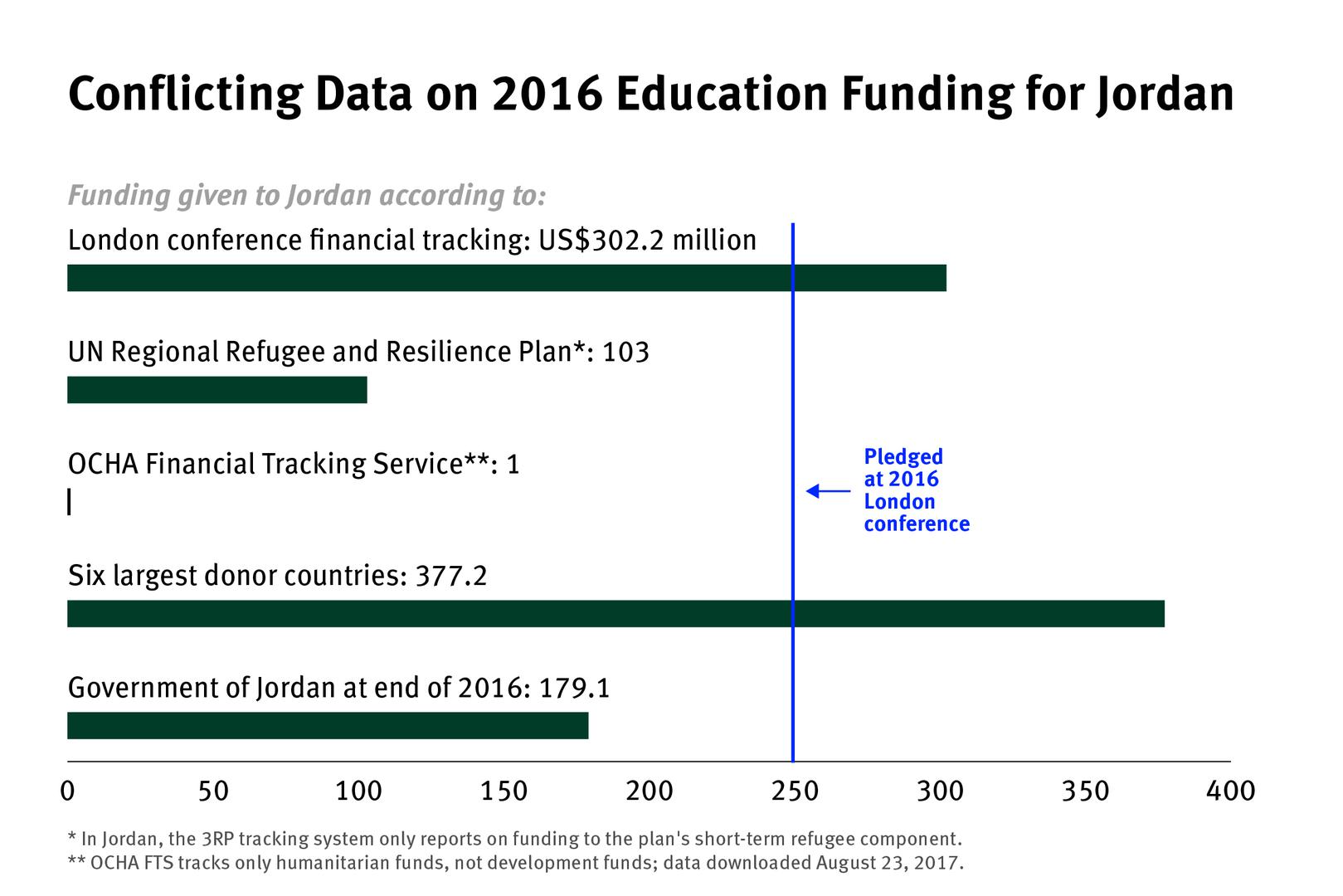

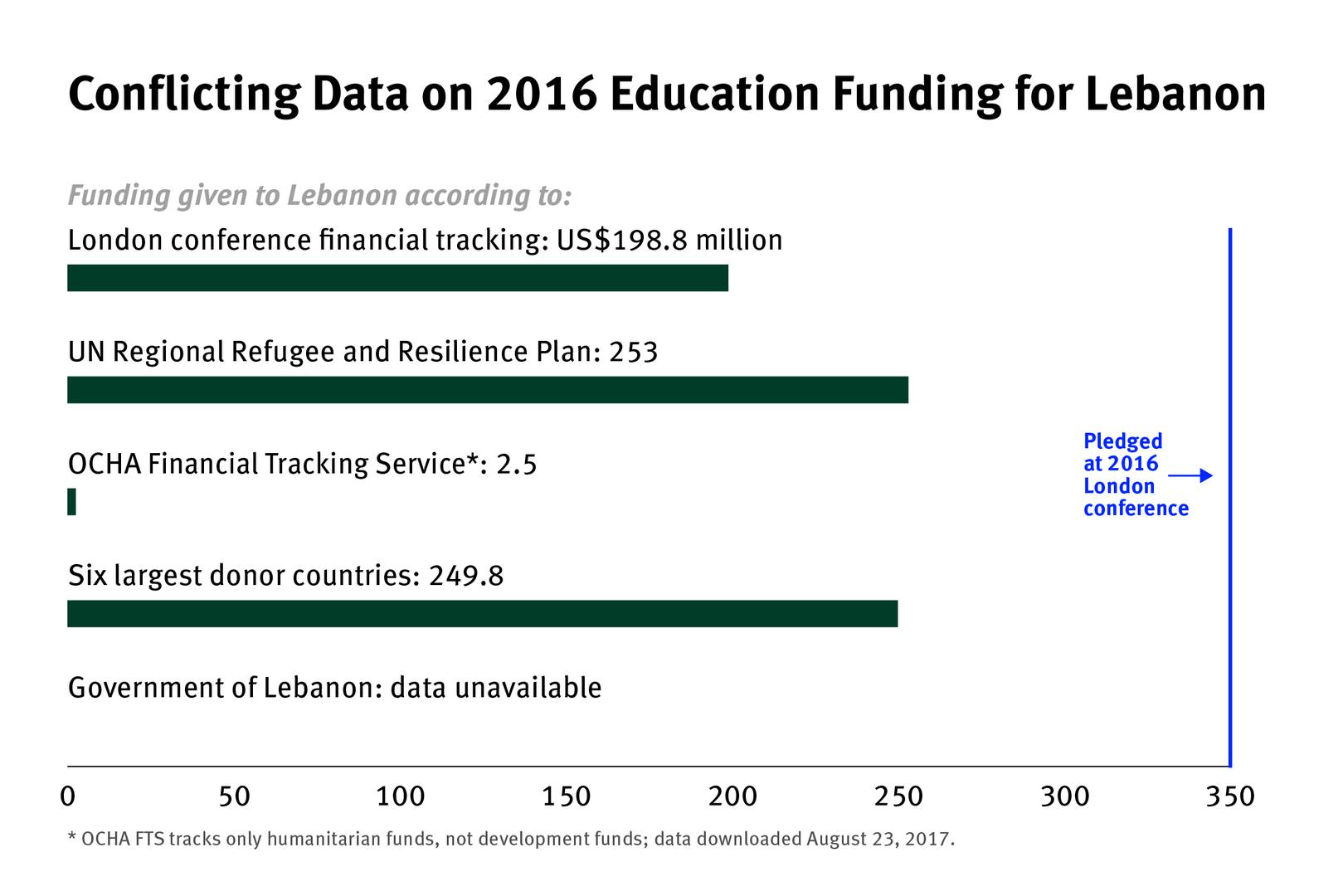

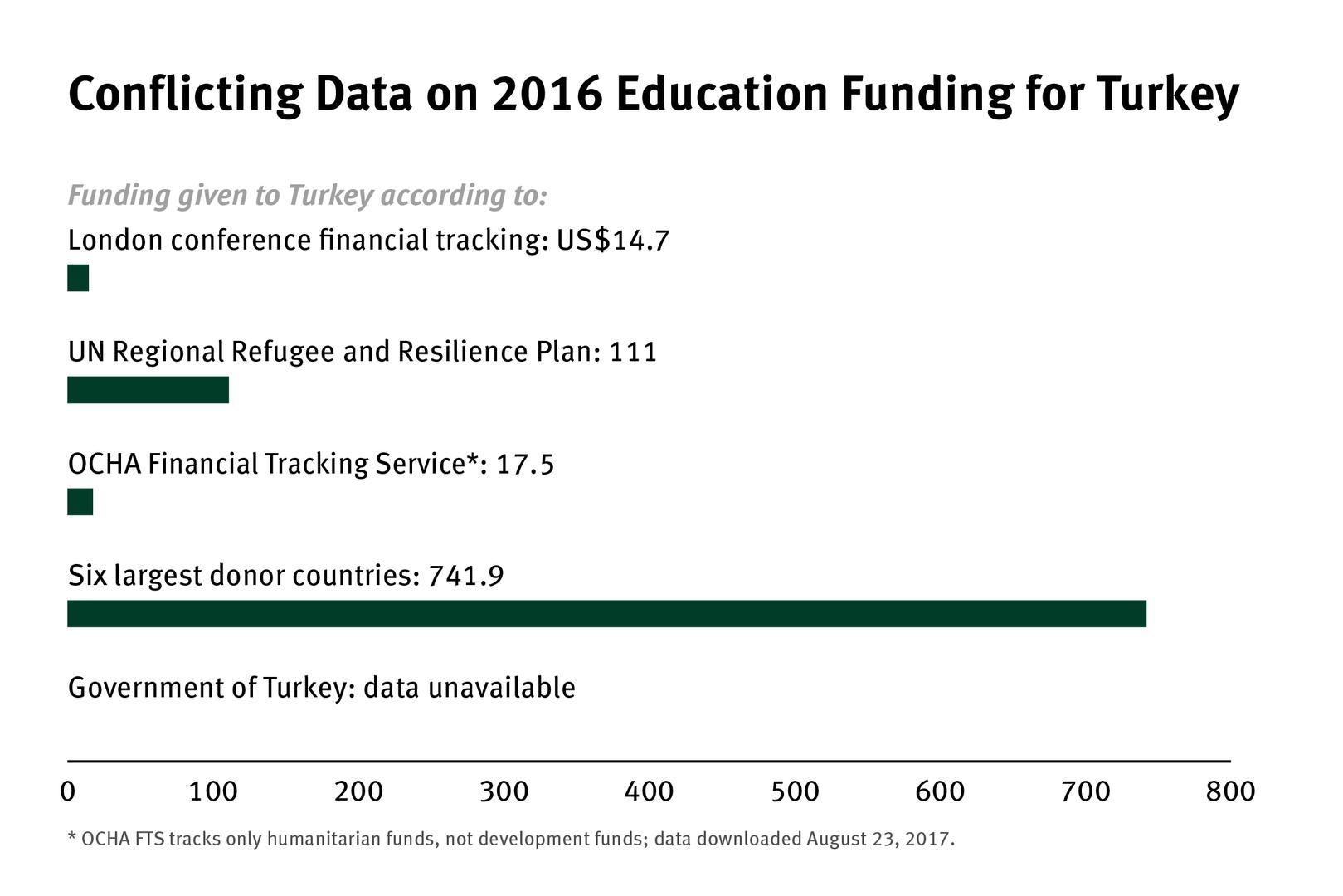

Different aid-tracking mechanisms reported substantially different amounts of education aid, and most public information was too vague or unclear to trace funding from a given donor to education projects in a given host country. Of the education funding that was sent, much did not arrive until after the start of the school year – too late to enroll the children it was intended to help. In some cases, donors had double-counted the promised funds.

More detailed, comprehensive information on education aid is needed to assess whether donors have met their pledges and provided aid in a timely way, and whether the activities being funded address key obstacles that are hampering education for Syrian refugee children. Donors, implementing agencies, and host governments need this information to coordinate their efforts and avoid gaps or overlaps in aid.

Turkey received about US$742 million for education in 2016, mostly from the EU, but United Nations agencies in Turkey received only US$111 of the US$137 million in education aid they asked for. Various reports said that only between US$14.7 and US$46 million was received by the beginning of the school year.Donors agreed to provide about US$250 million for education in Jordan and US$350 million for Lebanon in 2016, and acknowledged that much of the aid should be delivered before the beginning of the school year, to make it possible hire teachers, buy books, and plan education programs. But by early September 2016, Jordan faced a US$171 million shortfall, Lebanon US$181 million. By the end of the calendar year, Jordan still had a US$41 million budget gap, and Lebanon US$97 million.

The EU was the biggest education donor for Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey in 2016, giving more than US$776 million (€739 million). The EU gave the funding through three channels: its humanitarian arm, ECHO; its Facility for Refugees in Turkey; and the Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syria Crisis. The first two reported detailed information about funding, but the Trust Fund did not. An EU data portal is supposed to track all EU aid, but it listed only four 2016 education projects in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, when there were many more.Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, for their part, probably undercount the number of Syrian children who need education. They count only Syrians registered as refugees, but nearly 1 million refugees in Lebanon and Jordan are not registered. In addition, enrollment estimates may be inflated. Jordan has improved its data collection, but it found 45,000 fewer Syrian children enrolled in the 2016-2017 school year than previously reported.

The US government told Human Rights Watch that it had given US$1.4 billion in humanitarian aid for both Syria and the region in the 2016 US fiscal year, but it is unclear how much of that money went to education for refugee children. The US Agency for International Development reported that it provided development aid of US$248 million for education in Jordan, but its own aid tracking database only accounted for US$82 million, and a Jordanian government database listed only US$13 million received for education from the US in 2016.

The German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development committed US$249 million (€237.1 million) for education. The ministry is transparent, but the published information has shortcomings, such as not including disbursement dates. The ministry says that these shortcomings are due to its IT infrastructure.

The UK, through its Department for International Development (DFID), provided US$81.8 million (£57.2 million) for education in Jordan and Lebanon in 2016. The UK published detailed information about the date funds were given, and for what projects.

The Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said that Japan gave US$25.5 million for education in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey in 2016, but so little public information is available that it is impossible to determine when this aid was delivered or what it supported.Norway provided at least US$31.9 million (NOK 266 million) for education in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey in 2016. Norway published detailed information, but could improve by publishing aid data in the International Aid Transparency Initiative format, an agreed common standard. The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) said it aimed to do so by December 2015, but had not published any data by July 2017.

Human Rights Watch has reported extensively on obstacles to education in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan, including policies that make school-related costs unaffordable by contributing to refugee families’ poverty, and restrict children’s ability to access or enroll in schools. Greater transparency on education funding could help to show why enrollment goals are being missed, identify the responsible parties, and pressure them to improve. It could pinpoint the extent to which host country policies, as opposed to insufficient donor funding, are keeping children out of school.

“Despite global concern about Syrian refugee children, it is still impossible to find answers to basic questions about whether their key educational needs are being met,” Rau said. “Donors should fix the transparency deficit that is undercutting their own support for Syrian children, who cannot afford to wait any longer to get back into school.”

Source: HRW