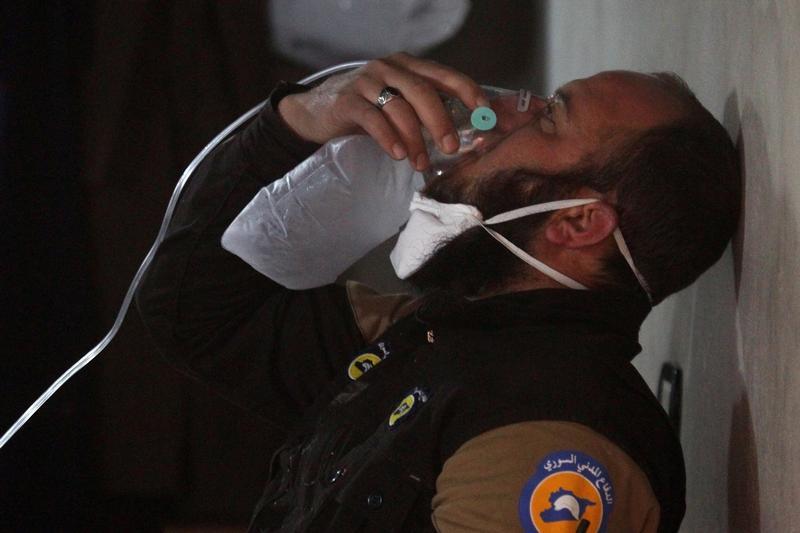

(Beirut) – International efforts to deter chemical attacks in Syria in the year since the devastating sarin attack on Khan Sheikhoun on April 4, 2017, have been ineffective, Human Rights Watch said today. Human Rights Watch has collated and analyzed evidence of chemical weapons attacks in Syria between August 21, 2013, the day of the deadliest chemical weapon attack in Syria to date, and February 25, 2018, when the Syrian government used chlorine in the besieged enclave of Eastern Ghouta.

The information, based on data from seven sources, shows that the Syrian government is responsible for the majority of 85 confirmed chemical weapon attacks. The data also show that the Syrian government has been largely undeterred by the efforts of the United Nations Security Council, the international Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), and unilateral action by individual countries to enforce the prohibition on Syria’s use of chemical weapons.

“In Syria, the government is using chemical weapons that are banned the world over without paying any price,” said Lama Fakih, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “One year after the horrific sarin attack on Khan Sheikhoun, neither the UN Security Council nor the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons has acted to uphold the prohibition against chemical weapon attacks.”

On April 4, 2018, the UN Security Council will meet to discuss the situation of chemical weapons in Syria. Members of the Security Council should find an alternative to the Joint Investigative Mechanism, a group that the Security Council and OPCW had tasked with identifying the party responsible chemical weapons attacks, but whose mandate was not renewed because of a Russian veto. The Security Council should impose sanctions on officials involved in the Khan Sheikhoun attack.

The sarin attack on Khan Sheikhounwas the largest chemical weapon attack in Syria since the government acceded to the Chemical Weapons Convention in October 2013. The government acceded to the convention following the chemical weapons attacks in Ghouta on August 21, 2013, when the Security Council demanded that the Syrian government destroy its chemical stockpiles, weapons, and production capacity.

In June 2014, the OPCW announced that it had shipped Syria’s declared chemical weapons out of the country for destruction, though it continued attempting to verify the accuracy and completeness of the Syrian declaration. Nevertheless, several incidents of the use of the chemical weapons in Syria have been reported, including by the Syrian government. As part of a strategy to re-take areas held by anti-government groups, the Syrian government has conducted coordinated chemical weapon attacks, including in Aleppo in December 2016 and likely in Ghouta in January and February of 2018.

On April 4, 2017, an aircraft attacked Khan Sheikhoun, a town held by anti-government forces in Idlib governorate, with sarin, a toxic chemical. Human Rights Watch investigated the attack and found that all likely evidence pointed to Syrian government responsibility. On October 26, the Joint Investigative Mechanism confirmed that the Syrian government was responsible. On November 16, the Russian government vetoed a UN Security Council resolution to renew the group’s mandate and on November 17, it ceased operations.

Russia has also used its veto at the Security Council to prevent holding the Syrian government accountable for its violations. That includes vetoing a resolution along with China that would have referred the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court on May 22, 2014.

Since the Joint Investigative Mechanism ceased to operate, the Syrian government has likely carried out at least five more chemical weapons attacks. There is no UN or OPCW entity to identify the party responsible for these attacks. And beyond unilateral sanctions by countries like the United States, France, and the European Union, those responsible have not been held accountable for the use of these weapons.

The sources Human Rights Watch used for this analysis are: Human Rights Watch research, the Joint Investigative Mechanism, the UN Commission of Inquiry, the OPCW Fact-finding Mission in Syria, the United Nations Mission to Investigate Allegations of the Use of Chemical Weapons in Syria, Amnesty International, and Bellingcat. In some cases, multiple sources investigated the same attack, while in others only one investigated it. The sources selected are independent and document violations based on witness and victim evidence, analysis of open source material, and – where available – physical samples. The 85 attacks reflect attacks that have been investigated by at least one of these sources and made public. The total number of actual chemical attacks is likely higher.

Human Rights Watch classified the data based on the organizations’ findings. Human Rights Watch has not independently verified attacks that it did not investigate. Of the 85 chemical weapon attacks analyzed from these sources, more than 50 were identified by the various sources as having been committed by Syrian government forces. Of these, 42 were documented to have used chlorine, while two used sarin. In seven of the attacks, the type of chemicals was unspecified.

The groups found that the Islamic State group (also known as ISIS) carried out three chemical weapon attacks using sulfur mustard. One attack was by non-state armed groups using chlorine. Those responsible for the remaining attacks in the data set are unknown or unconfirmed.

The OPCW is also mandated with protecting and executing the international Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction. The Conference of the OPCW is empowered by Article XII to take “necessary measures to ensure compliance with this Convention and to redress and remedy any situation which contravenes it,” including the use of collective measures such as sanctions.

But despite confirmed use of sarin by the Syrian government by both the Joint Investigative Mechanism and the OPCW’s own fact-finding mission, the OPCW has not taken any collective measures. The OPCW should suspend and sanction the Syrian government for its failure to comply with the Convention, Human Rights Watch said. If the Security Council and OPCW continue to drag their feet, it is a signal that member countries need to individually hold the Syrian government accountable and re-instate a system to identify responsibility for attacks.

“Despite the incentives to act, the UN Security Council and OPCW are silently watching on as Syria transforms the nightmare of chemical warfare into reality,” Fakih said. “It is high time to do right by the victims of the attack and the international standard set in the chemical weapons treaty.”